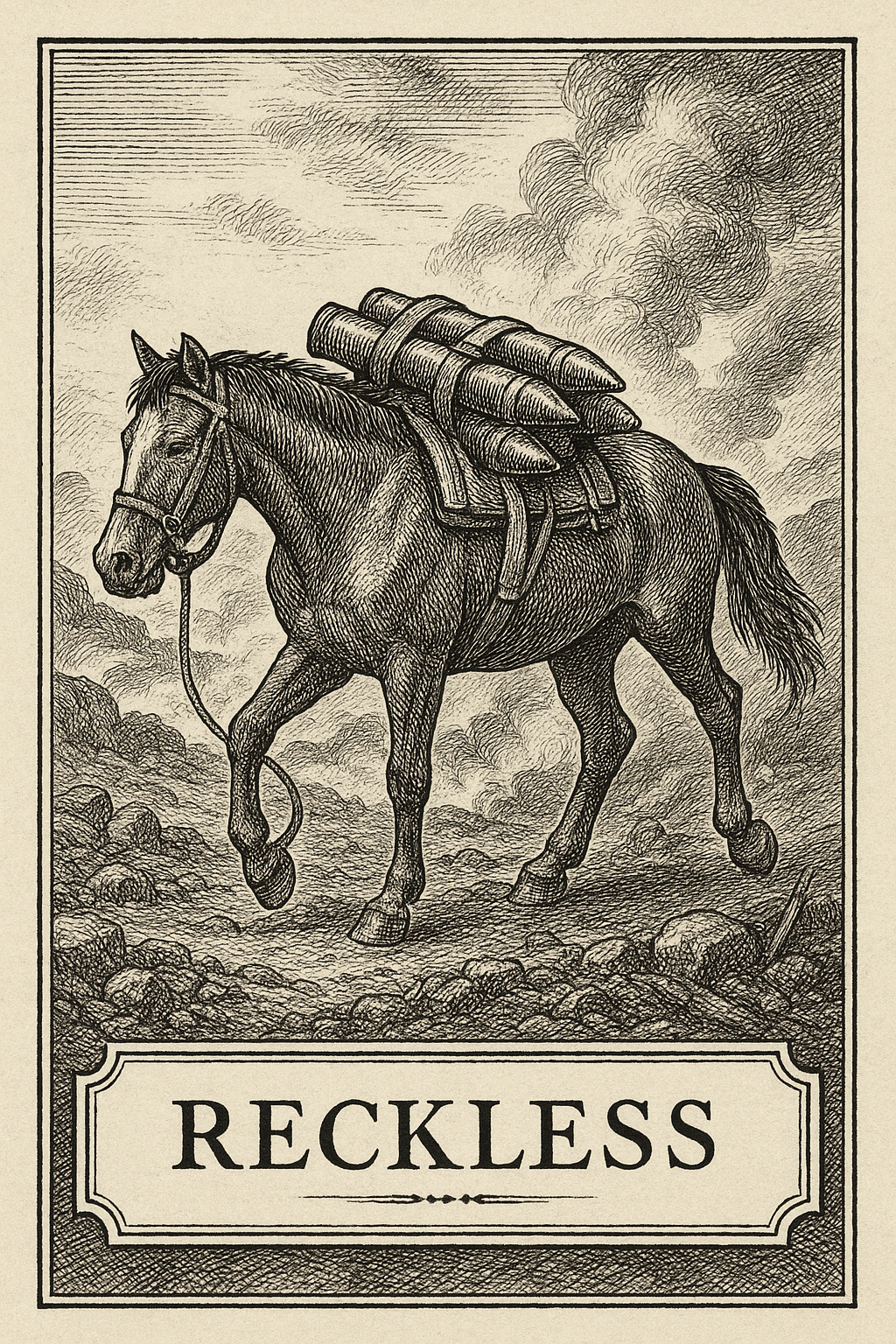

Reckless

Two wounds, no fear, and a taste

for beer.

March 1953, Outpost Vegas — the snow melted into red mud, and the smoke hung so thick you could taste it. Marines yelled for more shells, and through the chaos came a small chestnut mare with a white blaze, head down, hauling twenty-four-pound recoilless-rifle rounds up the ridge. She’d been doing it all day, a living supply line in a battle where even mules refused to climb. Shells screamed overhead; she didn’t flinch. She just chewed her rope and waited for the next load.

Months earlier she’d been a Korean racehorse named Flame, purchased for $250 by Lieutenant Eric Pedersen. The deal was simple: one ex-racehorse for one mission. What he got instead was a Marine. Reckless joined the Recoilless Rifle Platoon of the 5th Marines, carried ammunition like a truck with hooves, and memorized the trail so completely that when her handlers were hit, she kept walking it alone. At first they laughed; then they saluted. Someone drew up pay forms, issued her rations, even gave her a serial number. In a military built on categories, she slipped into the system as both transport and myth.

She weighed nine hundred pounds and carried almost that much up and down those slopes. Marines counted fifty-one trips in one day—over nine thousand pounds of shells—without a single misstep. A chunk of shrapnel tore through her flank; another cut above her eye. They patched her with battlefield gauze and whiskey and sent her back out before the bandages cooled. She drank coffee in the mornings, beer at night, and had a particular weakness for scrambled eggs. The men said she liked the taste of cordite better than oats.

Reporters eventually found her, of course. They called her “the little mare that could,” as if she’d stumbled out of a children’s book and into a trench. But the men who served beside her told a different story—of a creature that didn’t understand surrender, that would step over the dead to deliver one more load because stopping had never been part of the plan. Colonel Eustace Smoak wrote later, dry as a casualty list, “She did more work than most privates and complained less than any sergeant.”

When the guns finally went quiet, Reckless came home with the survivors. She marched in parades, posed for photos, and received her promotion to Staff Sergeant with all due ceremony. Camp Pendleton gave her a stable with her name on the door and a view of the sea she’d never asked for. Visitors fed her apples; the Marines kept bringing beer. She foaled four times and lived another fifteen years—long enough to see the war fade into footnotes and black-and-white documentaries.

She died in 1968 and was buried with full military honors. Her service record lists the medals, the wounds, the campaigns; it omits the smell of smoke, the hill that never stopped climbing, the silence that followed when she was finally still.