Wisdom

The Bird Who Outlived the War

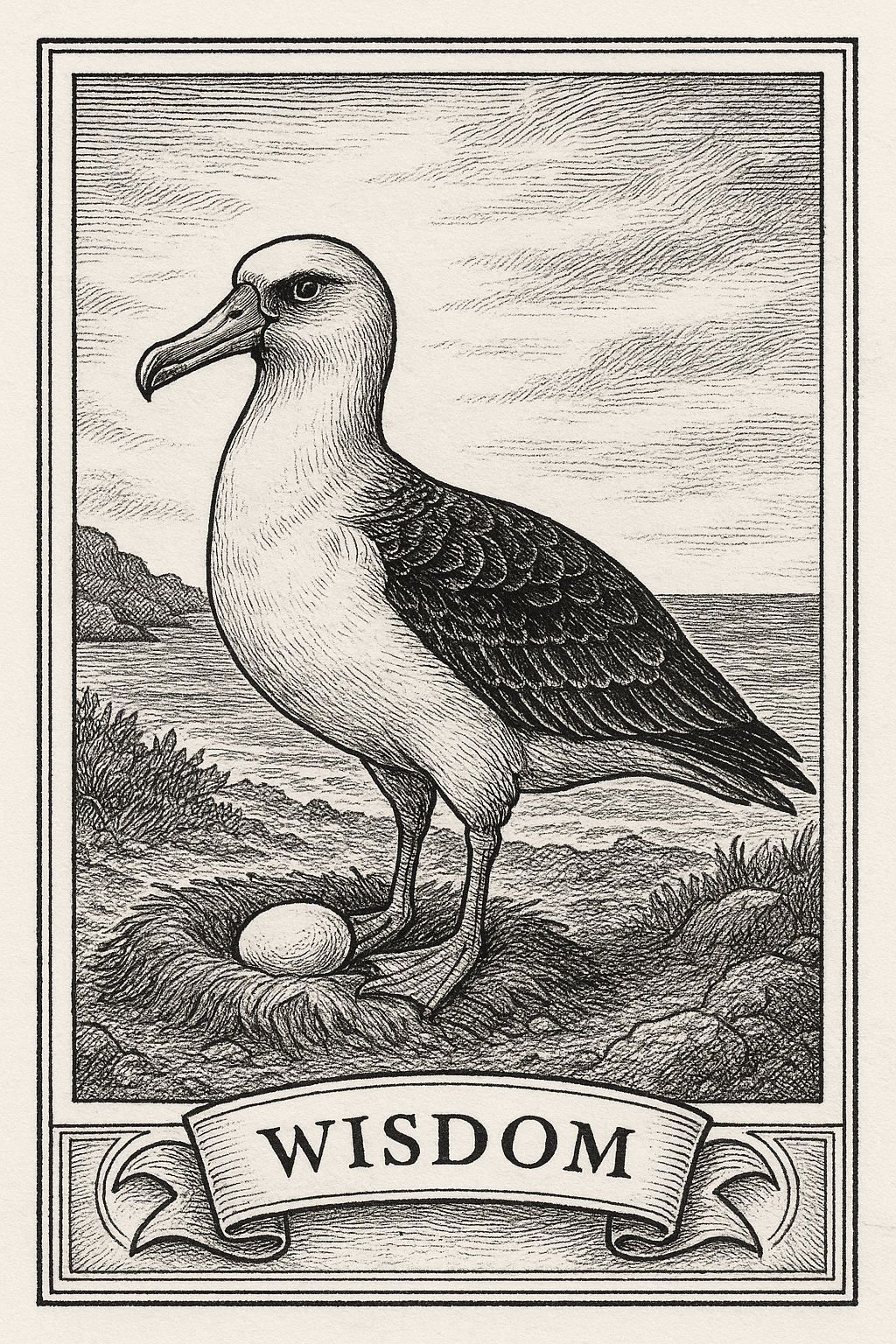

December 29, 2011, Midway Atoll, North Pacific Ocean – The wind off the reef smelled of salt and jet fuel. Rain came sideways, dragging mist across the cracked concrete runways where the last war never quite ended. A field biologist in a faded NOAA jacket crouched near a tuft of naupaka shrub, clipboard soaked, pencil trembling in the wind. Beneath the shrub, an albatross sat motionless, eyes half-lidded, feathers ruffling like the sea itself. She was banded — Z333, the metal tag dull from decades of salt. The bird shifted her weight and revealed, tucked under her body, a single white egg.

The biologist squinted, rechecked the band number, and muttered something halfway between a prayer and profanity. Because by every known law of biology, this should have been impossible.

The bird was sixty-one years old.

Wisdom, the oldest known wild bird on earth, was nesting again.

She had first been caught and tagged in 1956, when Dwight Eisenhower was president and Midway Atoll still bristled with military antennas and radar domes. Chandler Robbins, a young U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service scientist with a sunburn and a clipboard, had been banding Laysan albatrosses to track migration patterns. He’d held the young female gently while fitting her with the aluminum ring, not realizing she would outlive him, his research, and the entire Cold War that funded it.

She was just another bird then — one of hundreds, sleek and gray-white, eyes rimmed in charcoal, built for wind and distance. Albatrosses spend most of their lives in the air, gliding for thousands of miles across oceans without flapping. The field notes from that year were unremarkable: “Healthy adult female. Band number Z333.” No one wrote down that she bit the researcher twice.

Midway Atoll itself was a paradox — paradise paved with concrete. The war had left it half-wild, half-military. Airstrips cut through nesting grounds. Ammunition bunkers shared space with seabird colonies. The Navy referred to the albatrosses as “gooney birds,” nuisance hazards that clogged the runways and occasionally kamikazed into planes. By the 1950s, base commanders tried everything — fireworks, shotguns, bulldozers — to drive them off. The birds returned every time.

Wisdom was one of the stubborn ones. She nested on the same patch of coral grit year after year, through typhoons, fuel spills, and the slow dismantling of empire. When the base finally closed, the birds reclaimed the runways. They didn’t care who owned the island, only that it stayed above water.

For decades, no one noticed Wisdom again. Albatrosses live long lives — forty, fifty years — but they spend them invisibly, wheeling over endless water, sleeping on the wind. She must have circled the Pacific more times than any human aircraft, crossing from Japan to Alaska to the California coast and back, feeding on squid and flying fish, learning the map of air currents by heart.

Then in 2002, a field crew rebanding albatrosses on Midway caught her again. The tag still clung to her leg, dulled and pitted but readable: Z333. Robbins — now retired, white-haired, half-forgotten — saw the report and realized it was the same bird he’d banded nearly half a century earlier. “She’s older than I am,” he said, which wasn’t technically true but felt accurate.

From that point forward, Wisdom became more than a data point. She became a time traveler. When the Fish and Wildlife Service released the news, headlines called her “the world’s oldest mother.” She ignored them all, returning each year to her same nest site with the same unbothered precision. Every few years, she took a new mate — albatross pair for life, but they also outlive partners, and Wisdom had outlived several. Her latest companion was named Akeakamai — “lover of wisdom,” because humans can’t resist poetic symmetry. Together they raised chick after chick.

What separated Wisdom from the rest wasn’t just her longevity — it was her defiance of arithmetic. She’d survived the transition from handwritten field logs to GPS trackers, from diesel generators to drones, from war base to wildlife refuge. She’d weathered oil spills, invasive rats, and the 2011 tsunami that drowned tens of thousands of seabirds on Midway. When researchers returned after the waves receded, they found her alive, preening calmly beside her chick.

Her official file read: “Band Z333 recovered alive and nesting. Status: remarkable.”

The understatement became her legend. Year after year, she returned, banded, rebounded, renested. By 2018, she was estimated to have flown more than three million miles — enough to circle the planet 120 times — and to have raised over 35 chicks, possibly more. Scientists stopped trying to count accurately; it sounded mythic anyway.

To younger researchers, she was part mascot, part oracle. Interns whispered about her like a saint: “She’s still out there.” Her nest was a pilgrimage site. Each season they’d find her standing in the wind, feathers silvered at the edges, eyes bright and expressionless — the look of something that had seen everything and chosen not to comment.

Albatrosses are built for endurance, not speed. They don’t fight the storm; they become part of it. Their wings lock into place like the hinges of a glider, letting the wind do the work. Wisdom had perfected this. Even as plastic pollution filled the Pacific, she navigated through it, learning where the garbage gyres drifted and how to skim between them. She survived the shift from plankton-rich seas to warming ones, from clouds of squid to plastic bottle caps that looked like food. She raised chicks in an age when most albatross parents came home with bellies full of trash.

That might be her true miracle — persistence in an ecosystem designed to end. She wasn’t just long-lived; she was adaptive, a survivor of every human experiment conducted against her habitat. Her life became a ledger of human folly written in feathers: bombing range, landfill, oil spill, microplastic drift. Still, she returned.

By 2021, Wisdom was at least seventy years old. A photograph from that year shows her standing in front of her nest, the ocean behind her the same turquoise as in every photo before it. Only her eye gives her age away — not dimmer, but deeper, like a window through seven decades of wind.

The biologists still write about her in the cautious language of field reports: “Wisdom observed nesting again. Partner unknown. Egg viability pending.” Translation: she’s still doing the impossible.

Her fame has long since escaped the island. Documentaries, children’s books, conservation campaigns — she’s become a symbol of endurance in a collapsing system. A reminder that longevity isn’t the same as immortality, but it’s close enough for inspiration. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service once issued a press release so bureaucratic it looped back into poetry:

“Wisdom represents the resilience of the species and the importance of Midway Atoll as a refuge.”

Translation: she’s older than our mistakes.

Somewhere out over the Pacific, there’s always an albatross in flight, gliding from horizon to horizon. Odds are, one of them is hers — Z333, the eternal number on the ledger, written in salt and bone. She’s lived through wars, through decades of plastic, through every generation of scientists who’ve come to tag her and then aged out before she stopped flying.

Her story has no dramatic ending, no cinematic fade to black. There will come a day when she doesn’t return to Midway, when the tag stops showing up in reports. But for now, she’s still out there, alive, carving circles through the same skies that carried bombers and storms, outlasting everything that claimed permanence.

Some legends burn bright and vanish.

Wisdom just kept flying.