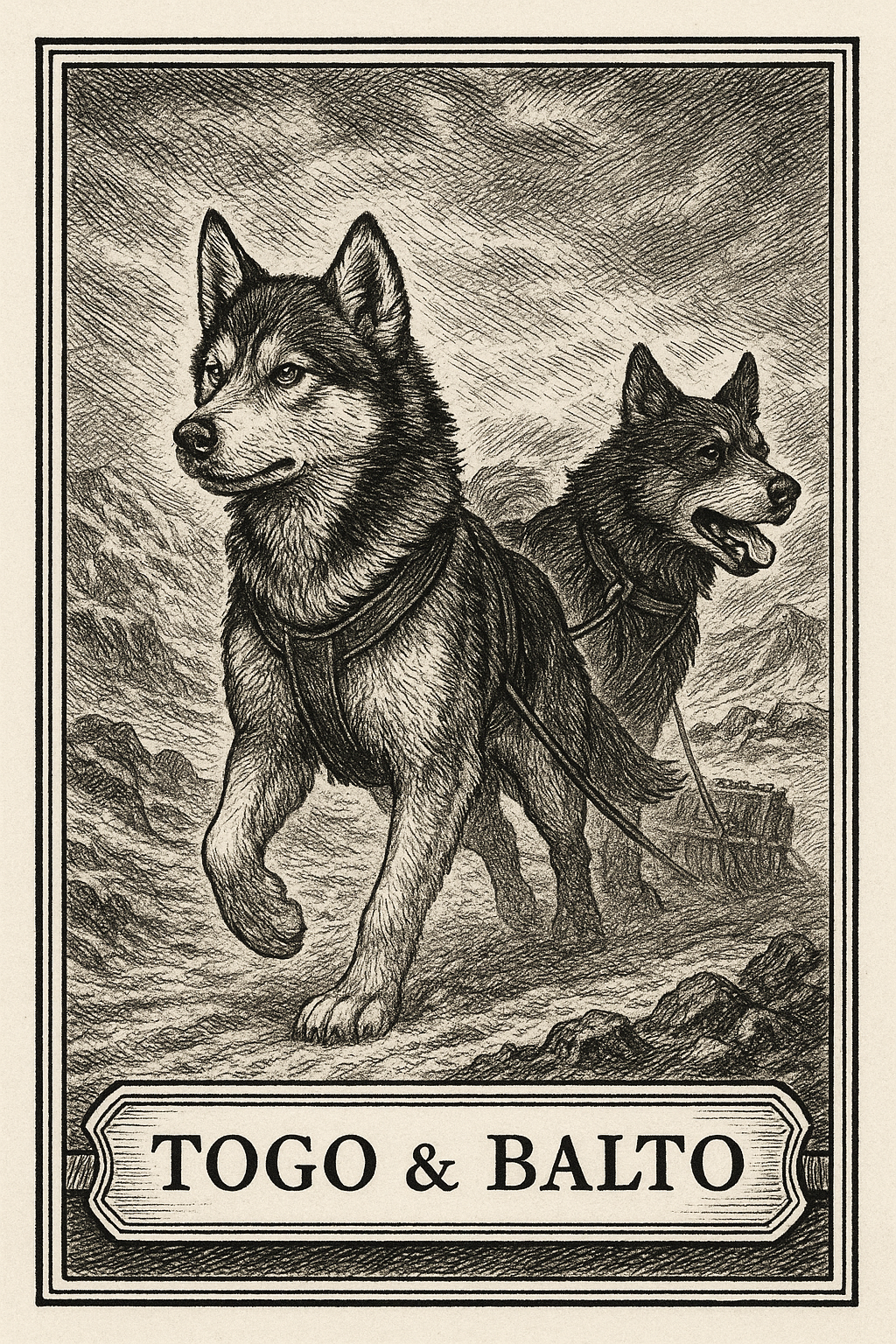

Togo & Balto

The Dogs Who Outran Death

January 27, 1925, Norton Sound, Alaska – The wind was screaming sideways, lifting snow into a white nothingness that erased the horizon. The temperature had dropped below forty below zero, a number that stopped meaning anything once your breath turned to needles in your nose. Leonhard Seppala hunched low over his sled, goggles crusted with ice, beard stiff as iron filings. In front of him, a twelve-year-old husky-gray dog with mismatched eyes leaned into the storm like it was a dare. His name was Togo, and he was pulling the world’s last chance for survival.

The crate lashed to the sled held ten pounds of glass vials — diphtheria antitoxin, wrapped in quilts, double-cased, insulated, the most valuable cargo on earth. Without it, the town of Nome — six hundred miles behind and counting — would choke to death in its own infection. The wireless stations were calling it “the icebound epidemic.” Doctors were already using the words “quarantine” and “mass fatality.”

And here was Togo, an undersized sled dog running into the kind of wind that peeled skin from bone, trying to shave off an hour for a town he’d never see.

They’d been on the trail for nearly eighty hours. Seppala’s team had covered more than 200 miles in the last three days, sleeping in bursts, eating frozen fish mid-run. Somewhere out in the blinding white was open water — the Norton Sound — and Seppala was gambling on a shortcut across the sea ice that could collapse at any moment. Every musher in Alaska had told him not to do it. He did it anyway.

When the ice cracked under them, it wasn’t a sound so much as a feeling — a low, rolling concussion beneath the sled. The dogs skidded. The runners split. In the chaos, the lead dog went airborne. Togo — thirty pounds of tendon, frost, and willpower — leapt across the widening fissure, dragging the line taut. Seppala, half-blind, threw himself down to anchor it. For ten heartbeats, they hung between life and the Bering Sea. Then the ice rejoined, groaning like a creature waking up. Togo hauled the team forward, step by step, until the sled reached solid ground again. The serum was still intact.

If you’d been there, you’d have sworn the dog was laughing.

Togo wasn’t supposed to be anyone’s hero. When Seppala first got him as a pup, he’d tried to give him away — too small, too wild, impossible to train. But when tied to a post for disobedience, Togo chewed through the rope, scaled a fence, and ran 75 miles through a blizzard just to find his team on the trail. From that day forward, he led the line. Seppala used to say he wasn’t a sled dog — he was “half dog, half wolf, all heart.”

By 1925, Seppala was one of the most experienced mushers in Alaska. The territory trusted him the way sailors trust compasses. When the call came that Nome’s children were dying, he was chosen to run the longest, most treacherous leg — through the Kaltag Mountains and across the Sound. “Fastest team we’ve got,” the relay organizers told him. “And you’ve got Togo.”

It was meant as reassurance. It sounded like a warning.

Meanwhile, in Nome, the doctor was running out of time. The diphtheria antitoxin on hand was spoiled, the supply ships frozen in the harbor, and the only aircraft in Alaska was disassembled for winter. The Governor called it “a logistical challenge.” The papers called it “a tragedy in progress.”

So the territory’s mushers — postmen, miners, mail haulers — volunteered for what the newspapers would later call The Great Race of Mercy. Twenty men. More than 150 dogs. Each team running a leg, handing off the serum like a flaming baton across 674 miles of ice.

The plan was insane. Which, in Alaska, meant it had a chance.

Togo ran his team 260 miles before passing the serum on. Then they turned around and ran 90 more miles home. In total, his distance was longer than all the other teams combined. When Seppala finally staggered into Nome, half-dead, someone asked if he’d heard who’d delivered the medicine.

“Balto,” they said.

Seppala blinked. “Who?”

February 2, 1925, Nome, Alaska – The blizzard had swallowed the world. Visibility was measured in inches, not yards. Gunnar Kaasen could barely see the lead dog at the end of his reins — a solid black husky named Balto, whose breath crystallized the instant it left his muzzle. The temperature hovered around minus fifty. Kaasen had the serum now — the final handoff. The town was only fifty-three miles away, but the trail might as well have been the moon.

They should have stopped. Every musher before him had pulled off the trail to wait out the storm. But Kaasen knew that every hour meant another child in Nome gasping for air. So he shouted once, cracked the whip, and the team surged forward into the white void.

Balto didn’t hesitate. He lowered his head, shoulders digging in, eyes slitted against the wind. The world vanished into noise and snow. He ran by instinct, following the scent of the trail buried beneath four feet of drift. The rest of the team followed his silhouette — a black arrow cutting through the blizzard.

At one point, Kaasen’s sled flipped. The serum canister flew off into the snow. He clawed at the ground with bare hands until he found it — metal frozen to his skin — and lashed it tighter this time. Balto stood motionless, waiting. Then, when Kaasen nodded, he set off again.

When they reached the outskirts of Nome just before dawn, the lamps of the town flickered through the snow like stars returning to orbit. Kaasen stumbled off the sled, frostbitten, nearly blind, the serum clutched to his chest. He staggered into the hospital shouting, “The serum! We have it!”

The nurse took it without ceremony and vanished inside. Outside, Balto stood in the wind, snow frosting his face. He had no idea he’d just saved an entire town. He just looked back down the trail, waiting for the next command that never came.

In the days that followed, the newspapers did what newspapers do: they simplified.

BALTO THE HERO DOG SAVES NOME!

The story ran coast to coast. Reporters wanted a face for the miracle, and Balto’s was available — photogenic, steady-eyed, noble. Seppala and Togo were still recovering hundreds of miles away when Balto became a household name. By the time they returned, Balto had a statue in Central Park.

Togo, meanwhile, got frostbite scars and a handshake.

The official record — the one typed on government letterhead — credits Balto’s team with the final 53 miles and “successful completion of serum delivery.” Togo’s team gets a line about “notable distance traversed under extreme conditions.” No medals, no interviews. The bureaucracy was tidy, the headlines were cleaner.

But among mushers — the people who knew what those numbers meant — there was no debate. Balto had delivered the last miles, but Togo had delivered the run itself. The old dog had run the farthest, faced the worst terrain, and crossed the open sea at night to shave days off the journey. Without Togo, there would’ve been nothing for Balto to finish.

That’s the absurd comedy of heroism: the world crowns whoever crosses the tape, not who laid the track.

Seppala never blamed Balto. He blamed luck. “Balto did his job,” he said later. “He led when he was told to lead. But it was Togo’s serum run.” It became a private creed among Alaskans: Balto got the glory; Togo got the distance.

In 1926, Seppala brought both dogs on a tour of the United States — a traveling proof of the impossible. Audiences cheered for Balto, the famous face. But Seppala always introduced Togo first. “The greatest sled dog that ever ran,” he’d say, hand on the old husky’s neck.

Togo lived out his days in Maine, sleeping on a bearskin rug, limping from the frostbitten joints that had carried history across the ice. When he died in 1929, the newspapers gave him a column inch. They’d already moved on to planes and heroes with cleaner fingernails.

Balto’s fame took a stranger turn. His owner sold him and the rest of the team to a sideshow promoter who displayed them in dime museums. When a group of Cleveland businessmen heard about it, they raised the money to rescue the dogs and bring them to the city zoo. Balto died there in 1933, blind and arthritic, surrounded by schoolchildren shouting his name.

In the years since, historians have tried to fix the record. The modern Iditarod Trail follows the route of the Serum Run, and mushers still invoke both names like twin patron saints. Togo for endurance. Balto for closure. Together, they turned a frozen relay into a story of shared defiance — a relay between courage and consequence.

Even now, their legend reads like a fable about teamwork the size of continents. The truth is less romantic and more miraculous: two dogs doing what dogs do best — running because someone they trusted said to run, refusing to quit because someone they loved was counting on them to finish.

When you see the bronze statue of Balto in Central Park, the inscription is simple:

“Endurance — Fidelity — Intelligence.”

But in Wasilla, Alaska, there’s another statue — Togo, leaner, older, still straining against the wind. His plaque reads:

“The true hero of the serum run.”

Two monuments, a thousand miles apart, facing opposite directions — as if still running toward each other through the snow.

If you measure greatness by finish lines, Balto wins.

If you measure it by distance, by hardship, by the part of the trail no one else could cross, it’s Togo all the way.

But maybe the real measure of it isn’t time or distance at all. Maybe it’s that when death came galloping across the Alaskan tundra in the winter of 1925, two dogs outran it — one to deliver the medicine, the other to deliver the legend.

And between them, they carried the world a few hundred frozen miles closer to mercy.