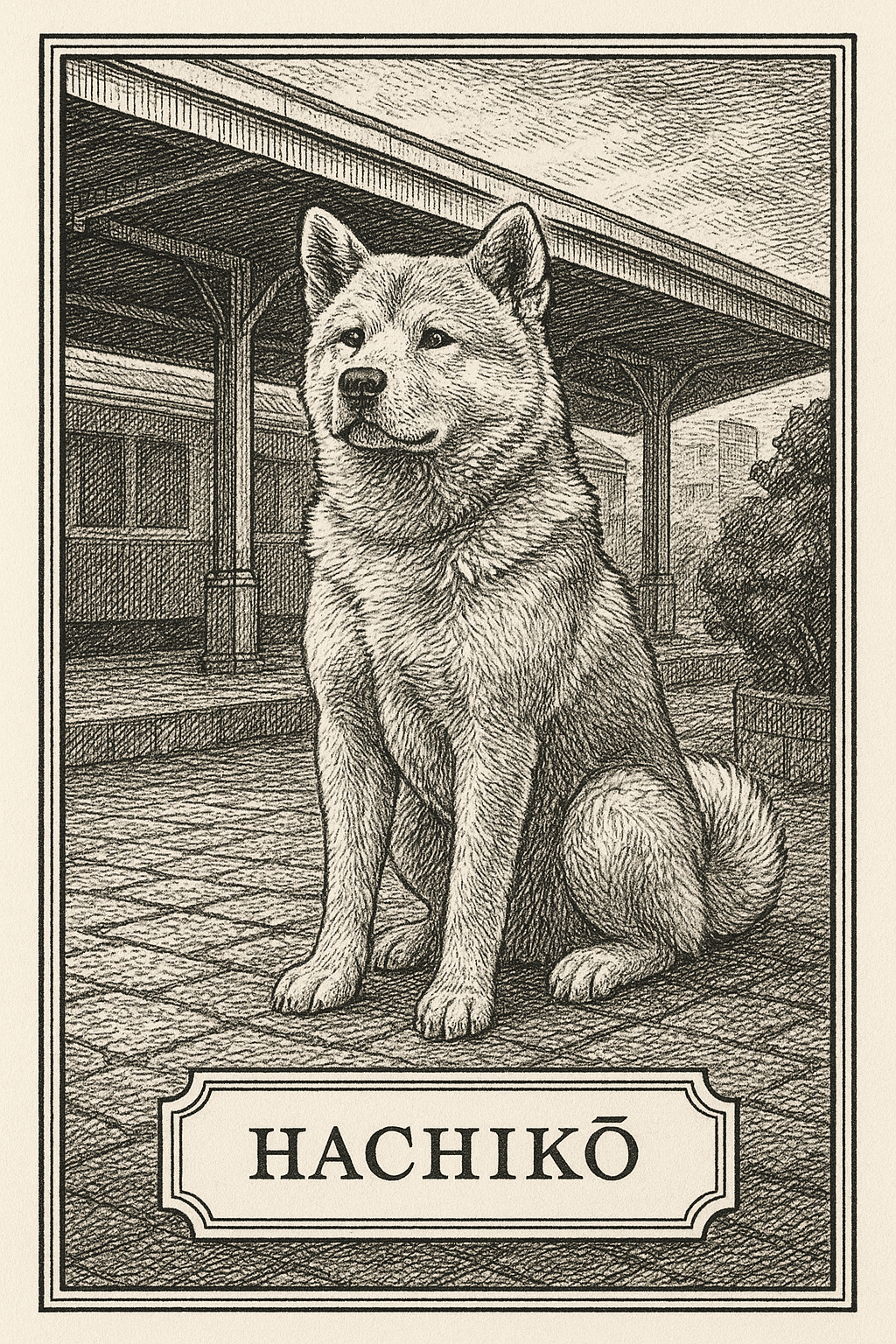

Hachikō

The Dog Who Waited for Time Itself

March 8, 1935, Shibuya Station, Tokyo – The morning crowd moved like steam: orderly, polite, unstoppable. The scent of roasted chestnuts hung over the station square. Commuters stepped around a motionless Akita lying beside the ticket gate, his fur mottled with age and rain. They’d seen him there for years, sitting perfectly still, eyes fixed toward the platform entrance, as if waiting for the world to return something it had already taken. When the first clerk of the day reached down to pat him, the body was cool. Hachikō, the most punctual soul in Tokyo, had kept his last appointment.

By then, he was less an animal than an institution. Vendors had built their stalls around him. Children left scraps of rice balls at his paws. The police looked the other way when he loitered past closing. Every evening for nearly a decade, he’d appeared at the same hour — 3:00 p.m. sharp — to greet a man who hadn’t stepped off that train since 1925.

Back then, the city had been younger, rawer, still rebuilding from quake and fire. Hachikō was barely a year old when he arrived in Tokyo — a cream-colored Akita pup from Odate, all ribs and promise, shipped in a wooden crate to Professor Hidesaburō Ueno, who taught agricultural engineering at the Imperial University. The professor lived in Shibuya, in a house with a tiled roof and a small garden of persimmon trees. He named the dog Hachikō — “eighth son,” for luck.

Their routine was monastic. Each morning, the professor would walk from his home to Shibuya Station, briefcase in hand, umbrella tucked under his arm. Hachikō followed, tail waving like a metronome. At the gate, the professor boarded his train. Hachikō sat and watched until it disappeared, then trotted home. In the afternoon, just before the return train arrived, he reappeared at the station, taking his post by the exit gate. Rain, snow, or heat — he was there. A one-dog honor guard.

It might have stayed a private ritual, a small testament to affection, if not for one ordinary May day in 1925. Ueno suffered a cerebral hemorrhage while lecturing at the university. He never came home. But Hachikō, ignorant of human schedules for grief, returned to the station that afternoon. And the next. And the next.

The first few days, commuters indulged him. The stationmaster tried to chase him off once, but the Akita merely sat down again, polite but immovable. Weeks passed. Then months. The calendar flipped over, the country changed cabinets, and still Hachikō waited, every evening, staring through the ticket gate toward the place where his master had always appeared.

People started to notice. Newspapers ran human-interest stories with headlines like “Faithful Dog Awaits Deceased Master Daily at Shibuya.” Tokyo fell in love with its own conscience. The image of the waiting dog became a civic fairy tale, a reminder that loyalty hadn’t yet gone extinct. University students stopped to bow to him. Station workers fed him leftovers from their bento boxes. A sculptor sketched him from the curb, muttering that bronze might one day do him justice.

By 1932, Hachikō was famous enough to have his own press clipping file. His photograph ran nationwide — ears sharp, eyes patient, posture perfect. The government, deep into its moral crusades about duty and sacrifice, adopted him as a living parable: a civilian embodiment of bushidō, pure devotion without command or reward. Bureaucrats wrote press releases calling him “a model of loyalty to be emulated by all citizens.” Children recited poems about him in school.

The irony was that Hachikō never understood any of it. He wasn’t loyal to an empire or an ideal; he was simply keeping a promise only he remembered making. Every day, he walked from his temporary lodgings to the station, waited for a train that wouldn’t arrive, and went home after the crowd thinned. It became clockwork. Passengers began timing their watches by his arrival.

As the years wore him down, his fur turned thin, his gait slower, but his schedule never changed. He endured stray attacks, police patrols, and the kind of winters that cracked stone. The station vendors gave him a cardboard shelter, then a wooden one. A local newspaper noted with amusement that “he receives more care than many citizens.” When a reporter asked the stationmaster why they tolerated the old dog, the man shrugged. “He’s never late,” he said.

In his final winter, Hachikō’s visits became shorter. He’d limp to the gate, rest on his haunches, stare at the crowd with milky eyes, then settle into stillness. When he died that March morning, they found him curled near the same spot he’d waited for ten years. The coroner’s report listed cause of death as filarial infection and old age. Tokyo listed it as heartbreak.

The reaction bordered on state mourning. Newspapers published obituaries. Floral tributes covered the pavement. Students wept openly. The government declared him a national symbol of fidelity. His body was preserved and mounted at the National Science Museum, labeled under “Canis familiaris — Akita breed,” though everyone knew it was more shrine than specimen.

That same year, the bronze statue went up at Shibuya Station. Hachikō’s sculptor cast him mid-sit, gazing toward the entrance where the trains came in, still waiting. During the war, the statue was melted down for weapons — loyalty feeding loyalty — but in 1948 it was recast from new bronze, unveiled by the original artist’s son. This time, the crowd applauded like the train had finally come in.

The legend metastasized. Postcards, films, children’s books — every generation revived him as proof that faith could outlive flesh. Tourists visit daily to pose beside the statue, phones held high, dogs tugging at leashes in the background. The modern station swallows thousands of commuters every minute, but at the bronze dog’s feet, time still runs slow.

Scientists, decades later, examined his remains and found evidence of cancer. The papers called it “a posthumous diagnosis of endurance.” Universities cited him in psychology courses about attachment and grief. Philosophers wrote essays arguing whether his vigil was an act of loyalty or habit. But that was all human noise, trying to domesticate devotion.

The truth is simpler. Hachikō was the creature who refused to update his faith to match the evidence. The world told him his friend was gone. He declined to believe it. For nine years, nine months, and fifteen days, he sat where love had last made sense.

And when he finally stopped waiting, Tokyo noticed. Not because he was gone — but because, for the first time, the train came in, and he wasn’t there to see it.