Kanzi

The Ape Who Spoke in Fire

June 1982, Des Moines, Iowa – The air inside the lab was cold enough to sharpen thought. Fluorescent lights hummed. Plastic tubing hissed. A low electronic chime marked the start of another trial — another morning in humanity’s longest conversation with itself. Across the room, a young bonobo named Kanzi sat on the floor with a lexigram keyboard the size of a coffee table, the kind with 256 colorful symbols instead of letters. The scientists waited for him to press one. He didn’t. He looked at them instead — then at the stove.

In one smooth motion, Kanzi stood, walked to the kitchenette, pulled open a drawer, and produced a pack of matches he wasn’t supposed to know existed. Before anyone could intervene, he struck one. The flame flickered alive in his dark eyes. “Hot,” he signed with his fingers, then grinned — a primate smile that belonged to both worlds.

That was the day Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh realized the experiment had slipped its leash.

Kanzi hadn’t been the intended subject. The research program at Georgia State University’s Language Research Center had been focused on another ape — Matata, his adoptive mother. She was supposed to learn to use the lexigram system, pointing to abstract symbols that represented words: apple, go, hide, play. Kanzi was just the child sitting on her hip, watching. The scientists didn’t teach him anything; they simply underestimated the value of an audience.

When Matata was removed from the room one day, Kanzi started pressing symbols on his own. Not at random, but in sequence. Chase. Hide. Matata. The syntax wasn’t perfect, but the intent was unmistakable. He wanted to play the same game the humans had been playing. By the end of that first session, he had used over 120 symbols correctly — something that had taken adult apes years to fake and graduate students years to justify.

They tested him again. And again. Each time, he understood new combinations without direct instruction. “Bring the pine needles to the refrigerator,” they’d say — an absurd task even for an intern. Kanzi would fetch pine needles, carry them to the fridge, and tap “good.” When they reversed the phrase — “Take the refrigerator to the pine needles” — he’d just stare until they laughed.

Language wasn’t supposed to work like this. The prevailing wisdom, carved in stone by linguists since Chomsky, held that syntax and grammar were human monopolies. But here was a bonobo, building sentences, asking for food, using verbs correctly, inventing jokes. He’d point to “chase” and then “Sue,” then run away giggling.

Over the years, Kanzi’s repertoire grew monstrous — 450 lexigrams recognized, more than 3,000 English words understood by sound alone. He could request specific meals (“grape juice, please”), describe what he wanted to watch (“TV. Movie. Jungle Book.”), and insult people who bored him (“bad,” “stupid,” “go”). The project’s funding reports, meanwhile, used phrases like “remarkable cognitive demonstration” and “unprecedented interspecies communication.” Translation: we have no idea how this is happening, but please keep the grant money coming.

By the 1990s, Kanzi was a celebrity with an NDA. He traveled to universities, appeared in documentaries, met journalists who called him “the talking ape.” He hated the cameras but liked the attention. His handlers swore he understood interviews — that he could tell when people were pretending to be impressed. Once, during a demonstration, a reporter accused the team of exaggerating. Kanzi looked at him, pressed “chase,” then “bad,” then threw a pinecone at his head.

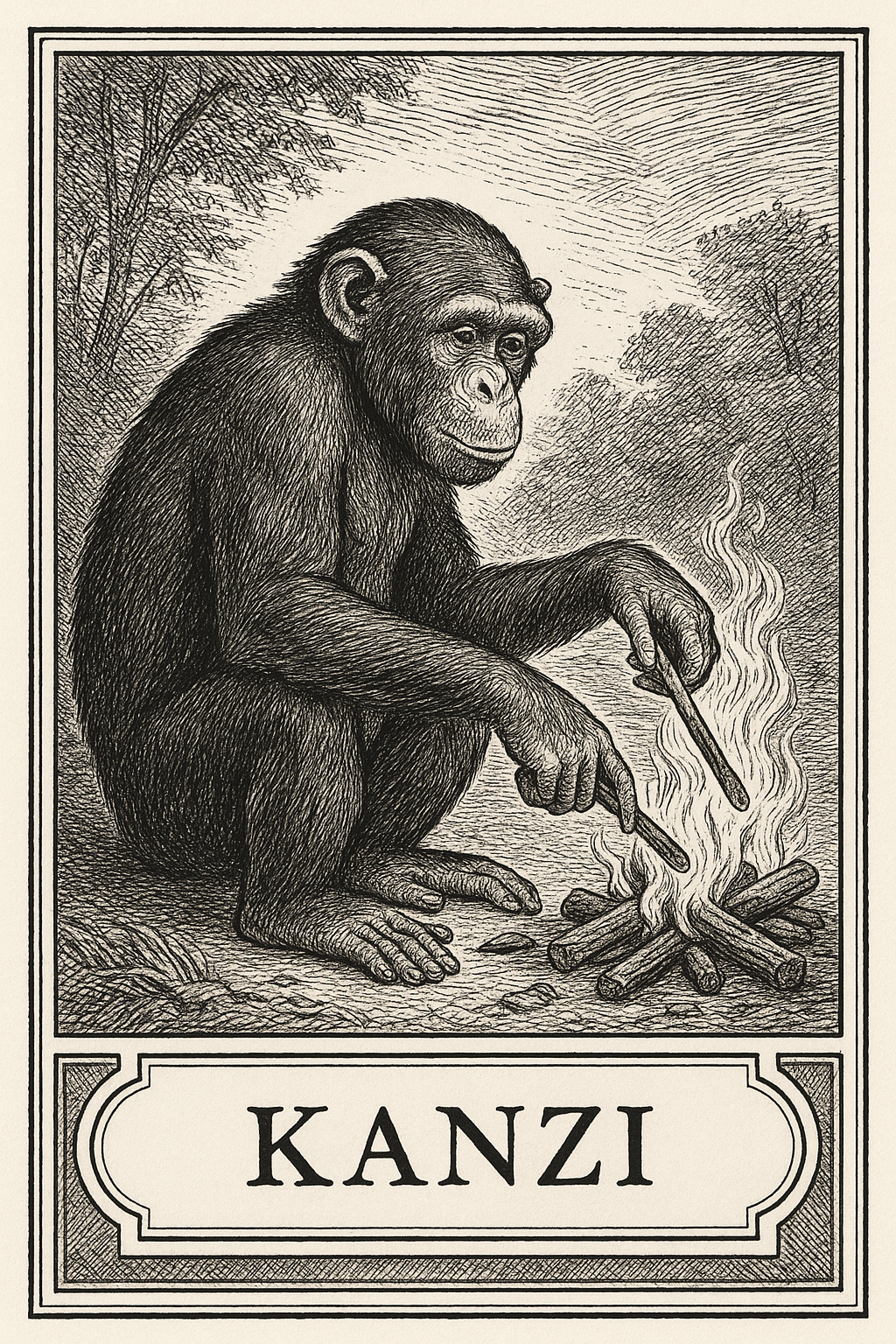

But the legend of Kanzi wasn’t built on novelty; it was built on transgression. He did what he wasn’t supposed to do. He broke the boundary between mimicry and meaning, between tool and self. He made fire — literally. Under supervision, he learned to strike flint and build a campfire to toast marshmallows, holding the stick just right, rotating it until golden. The staff joked that they’d accidentally created a Stone Age chef. When asked what he wanted next, Kanzi pressed the symbols for “TV,” “fire,” and “chicken.” Civilization, in three words.

His legend spread — a new Prometheus with opposable thumbs and patience for syntax. Scientists came from around the world to watch him work, each leaving more unsettled than inspired. Because once you’ve seen an ape understand verbs, you have to start asking questions about nouns like “human.”

He also loved music. Kanzi would hum along with melodies, keeping rhythm, preferring Peter Gabriel over anything else. When Gabriel visited in person, the bonobo recognized him instantly from a video. They drummed together for twenty minutes. Later, Gabriel called it “the most intelligent jam session of my life.” The official report filed it under “cross-species auditory response.”

Kanzi’s genius wasn’t confined to mimicry; he manipulated his environment in ways that looked alarmingly like culture. He passed learned skills to younger bonobos. He played cooperative games with human partners. He lied — once pretending not to know where the grapes were so he could eat them alone later. He teased his caretakers by misusing symbols on purpose, laughing when they corrected him.

Every act of communication became an act of rebellion. The scientists wanted control, consistency, proof. Kanzi wanted autonomy, jokes, maybe a banana. “He is a participant, not a subject,” Savage-Rumbaugh eventually wrote, perhaps the most honest line ever to appear in an academic paper.

And yet, for all his brilliance, Kanzi remained a captive genius. The cages grew larger over the years — from lab enclosures to forested sanctuaries — but the bars never disappeared. He grew heavier, moodier, more frustrated with the endless battery of tests. Like all celebrities, he learned to perform affection. He pressed the “love” symbol often, but only when cameras were running.

He’s still alive, in his forties now, older than most wild bonobos ever get to be. His eyes are clouded but still sharp, still calculating. When visitors arrive, he watches them like an anthropologist might watch a myth — curious to see what humanity believes about itself this decade. The official language surrounding him has only grown more absurd: “A key figure in cognitive linguistics,” “a living bridge between species,” “a milestone in anthropoid communication.”

Translation: he’s the only one of us who ever tried to talk back.

Kanzi’s story isn’t just about an ape who learned words. It’s about the humans who had to learn humility. He proved that intelligence isn’t binary — it’s a spectrum we built for our own comfort. That communication doesn’t require language; it just requires the will to be understood. That maybe the line separating our kind from his was drawn in pencil all along.

And that, for a few decades in a cold Midwestern lab, an ape named Kanzi managed to set it on fire.