Irish Ranger Wing / SAS in Ulster

(1975–present)

Ulster

Brotherhood Rank #200

"They said peace was the goal. Turns out, peace needed better shooters."

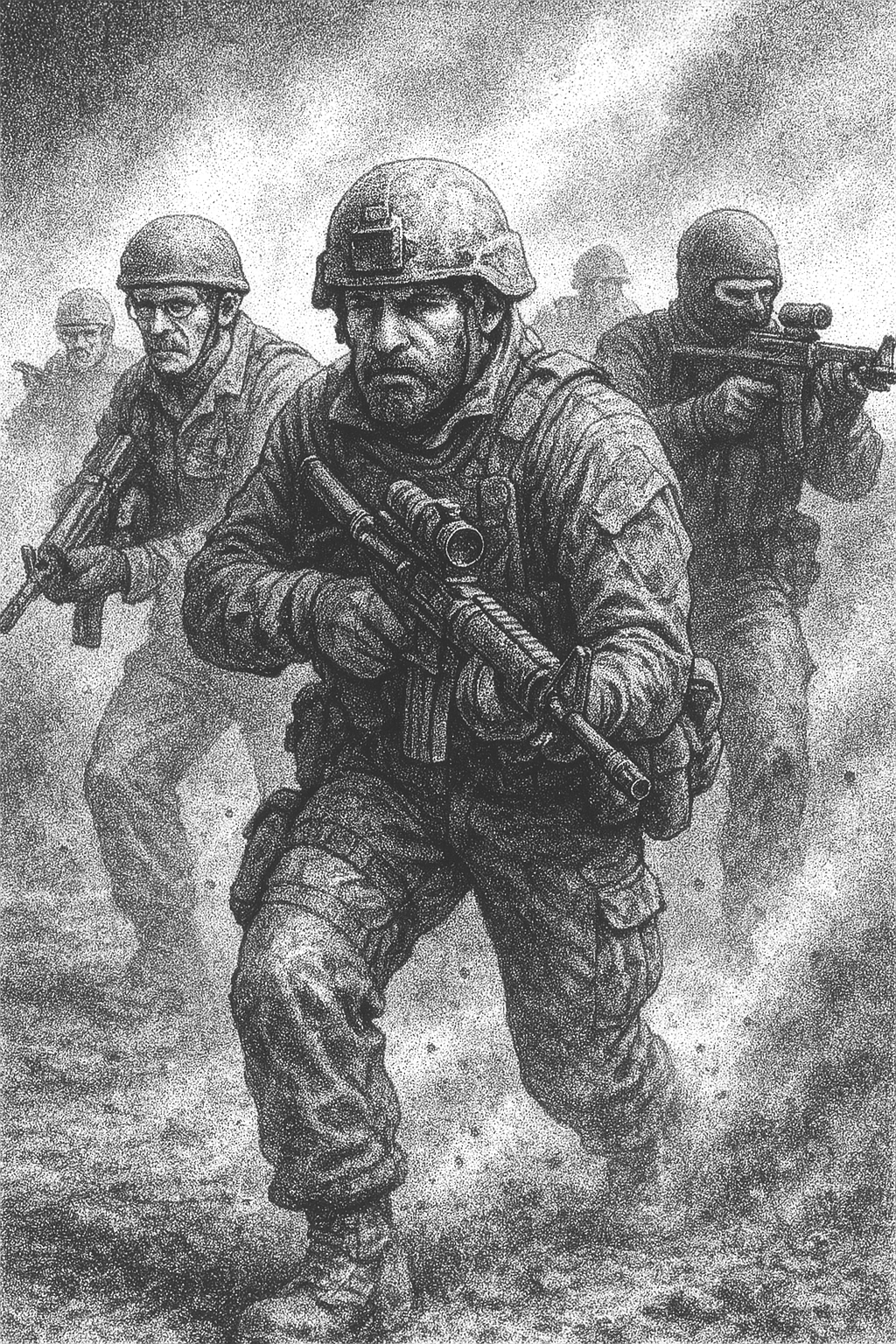

Night in South Armagh wasn’t dark—it was black. Thick, wet, Catholic black. The kind that swallowed light, muffled sound, and made even God crouch low behind a hedge. Somewhere out there, a milk truck packed with fertilizer and hate was rolling toward a checkpoint. The Irish Ranger Wing had been awake for forty hours, sweating under camo, waiting for men who wore no uniforms but carried the war like a parish curse. To the south, the SAS boys were already in position—faces smeared, rifles humming, each man with the same thought: one twitch, and the Troubles get shorter by six bodies.

Ulster was never a war anyone wanted to call a war. Officially, it was “an internal security operation.” Unofficially, it was two decades of urban hunting season—green berets, red berets, balaclavas, and a thousand shades of grey. When the British government realized the IRA were not just gunmen with accents but tacticians with PhDs in asymmetry, they brought in the one outfit that could outstalk ghosts: the Special Air Service. And when Dublin saw the same demons moving in their own backyard, they built their mirror image—the Irish Army Ranger Wing—born in 1980, baptized in secrecy, and fed on irony: Irishmen trained by the British to kill other Irishmen before the British had to.

Origins — The Ghosts with Maps

The SAS in Ulster had been at it since the early 1970s, slipping in under the bureaucratic euphemism of “special observation units.” They looked like farmers, smelled like pubs, and killed like surgeons. Their playbook: infiltrate, identify, neutralize. No flags. No applause. Just a quiet report and another man’s name crossed off a list.

Meanwhile, across the border, Ireland’s own Rangers were formed as a reaction to chaos. When the 1974 Miami Showband massacre and the Northern bombings made neutrality look naïve, the Irish government decided to grow some teeth. The Ranger Wing drew from the hardest of the Irish Defence Forces—paratroopers, commandos, and the kind of lunatics who smiled through swamp training in the Glen of Imaal. They studied with the SAS, the U.S. Rangers, and anyone else who believed sleep was a bourgeois luxury. Within a decade, they were operating like ghosts of the same fog, trading lessons and whiskey with their British counterparts while pretending in public they barely spoke.

What made them unique was their shared theater: not jungle or desert, but their own towns. Belfast and Derry became microcosms of modern war—urban ambushes, car bombs, and informant networks as lethal as minefields. Every streetlight was a potential sniper nest. Every friendly face could be wired to explode.

Offensive / Lethality — Hunting the Invisible

The SAS perfected the ambush—the kind that doesn’t look like a fight so much as a sudden correction in history. IRA cells learned to fear parked vans and strange tourists with bad haircuts. The Regiment’s kill ratio during covert ops was staggering: small teams neutralizing active units before they’d even loaded the detonators.

The Irish Rangers, though newer to the game, developed their own flavor of quiet murder. When deployed on counter-terror and hostage rescue, they worked in four-man fireteams, each man trained to take the same shot as his partner—a redundancy that meant failure had no excuse. Their shooting standard was SAS-level obscene: a one-inch group at 100 meters under stress, heartbeat, or hangover.

Offensively, they were forward momentum incarnate—fast, invisible, and surgical. Lethality? They made “measured response” look like poetry written in 5.56mm.

Defensive / Ruthlessness — The Long Game in the Long War

Defensively, both forces were masters of the miserable. They didn’t hold ground; they made ground irrelevant. Fortified watchtowers, covert listening posts, rural surveillance hides—every bush in Ulster seemed to have eyes. The men of the SAS and the Ranger Wing could wait for days in a bog, pissing into bottles, watching a farmhouse that might or might not contain their target. When the target emerged, the shot was clean, unanswerable, and often unclaimed.

Ruthlessness? These weren’t berserkers foaming at the mouth. They were professionals who’d simply amputated hesitation. After all, in Northern Ireland hesitation got you posthumous medals and burned-out cars. When the 1987 Loughgall ambush left eight IRA men dead—gunned down by SAS operators after attacking an RUC station—the message was brutal but clear: the crown had claws again. Even the Rangers admired the efficiency, though they couldn’t say it out loud.

Loyalty / Respect — A Band of Invisible Brothers

Among soldiers, both units were whispered about with a kind of reverence reserved for saints and psychopaths. SAS veterans who rotated out of Ulster often described it as the “thinking man’s Vietnam”—a place where the enemy drank in the same pubs and the rules of engagement were printed on rice paper. Ranger Wing operators, trained in the same dark arts, built their loyalty around silence. They didn’t boast; they didn’t leak. The unit’s motto, “Glaine ár gcroí, neart ár ngéag, agus beart de réir ár mbriathar” (“The cleanliness of our hearts, the strength of our limbs, and our commitment to our promise”), was half-prayer, half-psych test.

They respected their opposite numbers, even when those numbers wore British flags. In the dirty little intermission between terrorism and politics, the SAS and Rangers formed a kind of unspoken fraternity: two packs of hounds keeping the same countryside clear, while pretending not to see each other’s tracks.

Legend / Impact — The Shadow That Shaped Modern Warfare

Their legend grew quietly. In the 1980s, Belfast kids told bedtime stories about the “men with no faces.” IRA propaganda claimed the SAS used heart monitors and thermal sensors like some sci-fi death squad. The truth wasn’t far off. These units pioneered surveillance technology, urban infiltration, and close-quarter precision that modern special ops still imitate.

The Irish Rangers took those lessons global: UN peacekeeping in Lebanon, hostage rescues in Africa, counter-insurgency in Chad and Mali. The SAS, meanwhile, evolved into the template for every modern Tier One unit—Delta, SEAL Team Six, GIGN, even the Rangers themselves. The war in Ulster became their crucible: a long, grey apprenticeship in how to fight an enemy who looked like you, prayed like you, and probably had your cousin’s accent.

Impact? Measurable in doctrine, in dead men, and in the uneasy peace that eventually followed. When the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, it wasn’t politicians who’d made it possible—it was the invisible professionals who’d worn down the war until everyone was too tired to keep shooting.

Downfall / Legacy — The Price of Ghosthood

Neither unit “fell,” exactly, but they paid their toll. The SAS’s operations in Ulster remain classified and controversial—accusations of shoot-to-kill policies, rogue missions, and political deniability hang over their history like cordite smoke. The Rangers, though publicly lauded, carried their own ghosts. Some veterans drank themselves numb. Others couldn’t stop scanning rooftops years after discharge.

Both emerged into the 21st century as global professionals—polished, lethal, and curiously anonymous. Their work in Ulster taught the Western world that victory wasn’t about banners or parades—it was about patience, precision, and the quiet luxury of going home alive.

Their myth? Equal parts pride and denial. The British call it counter-insurgency genius. The Irish call it a necessary evil. The truth, as usual, lies buried somewhere under a hedgerow, in the rain, with two brass casings beside it.

Key Figures

Col. Jerry Ryan (Ireland, b. 1957)

A founding officer of the Ranger Wing and one of its first commanders, Ryan trained with both U.S. and British special forces and brought home a gospel of endurance and controlled violence. Cool under fire, fluent in understatement, and allergic to press cameras, he turned a fledgling unit into one of Europe’s elite. Known to demand that his men “shoot like surgeons and think like priests,” he set the Wing’s quiet standard of excellence.

Capt. Mick “The Ghost” Fallon (Ireland, 1962–1999)

A myth within a myth, Fallon allegedly infiltrated IRA logistics networks so deeply he attended two enemy funerals unnoticed. A sniper and linguist, he was rumored to be behind several cross-border operations never acknowledged officially. Killed in a car crash widely suspected to be less than accidental, his story lives on in barracks whispers and unmarked graves.

Maj. Peter Ratcliffe (UK, b. 1951)

SAS veteran of Ulster and later Gulf War fame, Ratcliffe embodied the Regiment’s cold professionalism. Decorated, blunt, and unapologetically lethal, he viewed the Troubles as “the longest chess game with live pieces.” His postwar candor made him both historian and heretic within the brotherhood.

Sgt. “Spud” Murphy (UK, dates unknown)

An Irish-born SAS NCO who joked he “joined the wrong side for the right reasons.” His reputation in South Armagh was that of a hunter who could smell Semtex from a mile away. Known for surviving three near-fatal ambushes, he earned respect from men who didn’t give it easily. Retired to a farm near Cork, where the locals pretend not to know his past.

Cpl. Niall Brennan (Ireland, b. 1969)

Ranger Wing operator and later UN peacekeeper, Brennan brought Ulster-born paranoia to international missions. Described as “charm wrapped around a tripwire,” he became a mentor for a generation of Irish commandos. His combat psychology lectures are still required reading in the Wing.

Sources

Taylor, Peter. Britain’s Secret War: The SAS in Northern Ireland. London: BBC Books, 1998.

Urban, Mark. Big Boys’ Rules: The Secret Struggle Against the IRA. London: Faber and Faber, 1992.

Bruce, Paul. The Nemesis File: The True Story of an SAS Execution Squad. London: Orion Books, 1995.

Power, Declan. The Siege of Jadotville: The Irish Army’s Forgotten Battle. Dublin: Maverick House, 2005.

Coughlin, Con. Soldiers of Fortune: The Story of the SAS. London: Macmillan, 2004.

The Bogside Times, “Rumors and Shadows: Who Watches the Watchers?” (imaginary pub newsletter, 1983)