Seljuk Ghulams

(c. 10th - 12th centuries)

Iran, Iraq, Anatolia, Central Asia

Brotherhood Rank #174

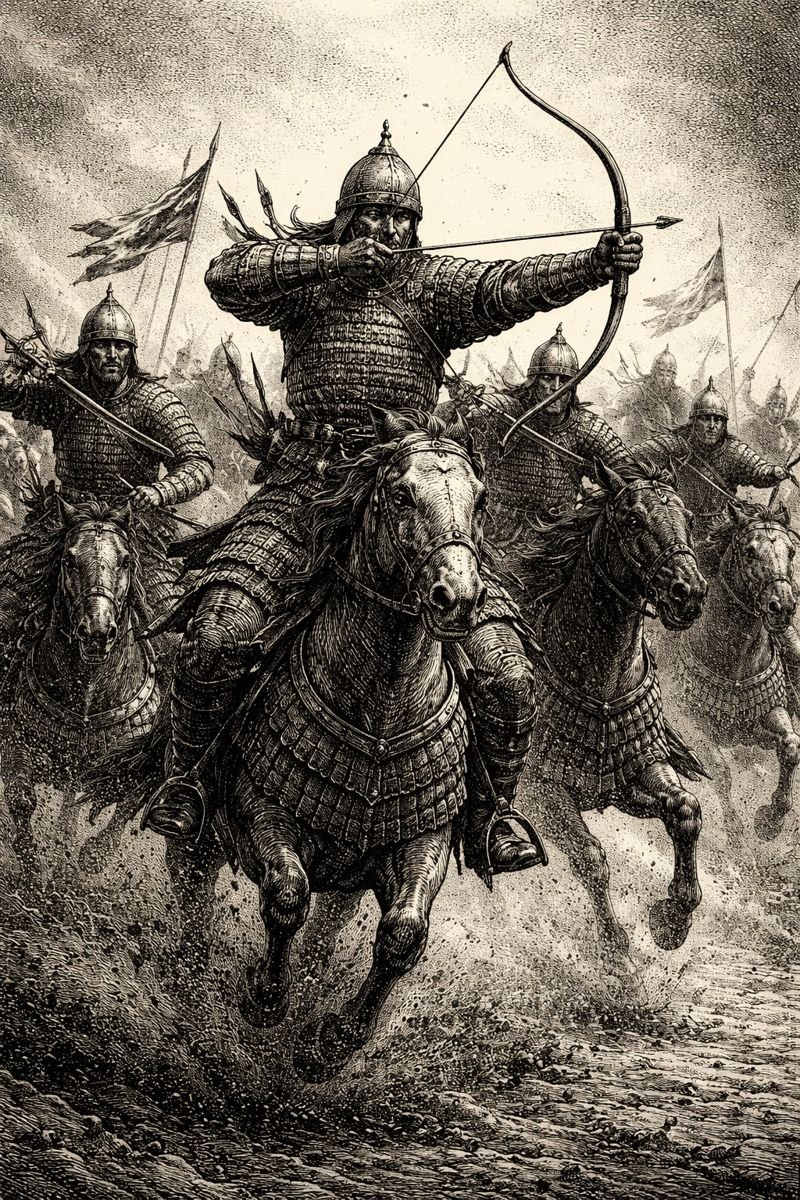

They came in chains that learned to march. Steel followed them like a second language, picked up young, spoken without accent. The Seljuk Ghulams entered history already sweating, hooves ringing, bows humming, the old steppe wind trapped in their lungs while a new faith cinched tight around their ribs. They were bought, sorted, renamed, drilled, and broken to shape, then loosed in disciplined waves that smelled of horsehair and iron filings. No warm-up. No childhood. The first memory was the weight of mail. The second was the sound a man makes when an arrow arrives before the thought that summoned it.

The Seljuk banners did not invent them; the world had been importing war for centuries. What changed was scale and confidence. The Seljuk court learned how to turn human cargo into a repeatable system, a production line of loyalty that answered to salary and scripture rather than clan or pasture. Ghulams rode at the center of campaigns that tore corridors across Iran and Iraq, that burst into Anatolia like a lungful of cold air. Their silence was the point. Tribal cavalry shouted and sang; ghulams advanced with a different music, the rasp of discipline. Chroniclers noticed the absence and mistook it for obedience. It was more complicated. They were loyal because the alternative had been erased.

Some later writers embroidered the beginning, turning boys into blank slates miraculously filled with Islam and obedience. Modern historians argue about ages, numbers, the ethics of conversion. The record is patchy where it should be sharp, sharp where it should be merciful. What remains clear is behavior. On the field, Seljuk ghulams showed a controlled appetite for violence. They did not waste arrows. They closed when commanded. They broke when ordered, and returned again. When they held, they held like a hinge, absorbing impact so others could swing.

This was not romance. This was a workforce trained to kill in patterns. Ghulams learned the rhythm of mounted archery until it seeped into their sleep, learned when to advance and when to pretend fear, learned the mathematics of exhaustion. They learned that mercy was a policy choice, not a feeling. They learned that names could be replaced, but scars could not.

The Seljuk state grew around them like scaffolding hardening into stone. Viziers trusted them because they had no uncles. Sultans feared them because they remembered everything that mattered. Their story begins in motion because it never stopped moving. When the dust finally settled, it was on graves that had learned how to line up.

Imported Steel, Manufactured Loyalty

The Seljuk use of ghulams did not appear ex nihilo. The Abbasid court had already refined the logic of military slavery, and Turkic youths had long been prized for speed, endurance, and a cultural comfort with horses. Under the Seljuks, the system became brutally efficient. Young captives, often from the steppe fringes, were converted to Islam, trained in arms, and integrated into households and units that functioned as both family and factory. Pay was regular. Equipment was standardized. Advancement existed, which is another word for hope rationed carefully.

Sources differ on recruitment methods and scale. Some describe purchases through markets; others hint at tribute and raids. Conversion narratives vary between sincere indoctrination and pragmatic assimilation. What matters on the ground is outcome. Ghulams did not fight as tribes. They fought as files. Their cohesion was contractual, enforced by stipends and punishments, by proximity to power and distance from home. It produced a peculiar psychology: fierce personal pride welded to institutional obedience, ambition channeled through service.

The Seljuk court, ruling within the loose sanctity of the Abbasid Caliphate, needed muscle that did not answer to local magnates. Ghulams filled that gap. They guarded palaces and spearheaded campaigns. They were deployed to remind governors who paid whom. Their presence recalibrated politics. A man with land could be argued with. A man with a unit of ghulams could be obeyed.

Training the Body, Editing the Past

Training was relentless and repetitive. Horsemanship came first, then archery, then the unglamorous work: formation riding, weapon maintenance, camp discipline. Punishment was public and instructive. The system depended on predictability. Superstition crept in where uncertainty lived. Amulets, oaths, prayers before dawn. Chroniclers note rituals without understanding their function. They were pressure valves.

Ghulams learned to be seen as interchangeable without feeling interchangeable. This is the trick. Identity narrowed to role and reputation. To fail publicly was to vanish privately. To excel was to be noticed by patrons whose favor could translate into command, land grants, even marriage into respectable families. Some rose high enough to forget their first names had been purchased.

On the Field: Hinges and Knives

Seljuk battlecraft blended steppe mobility with bureaucratic patience. Ghulams formed the disciplined core, capable of executing feigned retreats without collapsing, capable of holding ground while tribal auxiliaries swarmed. Mounted archery softened targets; shock followed when cohesion cracked. The ghulam advance did not shout victory. It measured it.

At Battle of Manzikert, ghulams operated within a larger Seljuk machine that outmaneuvered a heavier Byzantine host. Later chronicles exaggerate their singularity; modern scholars distribute credit more evenly. Still, their steadiness mattered. They were the spine that allowed the Seljuk body to bend without breaking.

Their lethality was not in berserk charges but in attrition. They exhausted enemies, cut supply lines, punished pursuit. Cruelty existed, but it was calibrated. Executions were warnings. Mercy, when extended, was strategic. This earned them a reputation that traveled faster than they did. Cities negotiated early when ghulams appeared at the horizon.

Power, Proximity, and Fear

Close to power breeds fear on both sides. Ghulams guarded sultans and viziers, heard secrets through walls, learned which doors stayed locked. Vizier Nizam al-Mulk understood their utility and danger. His administrative genius paired ghulam muscle with madrasa ink, law buttressed by lance. He also knew the cost. A disciplined armed class without kin could become its own kin.

Plots surfaced. Mutinies flared and were crushed. Loyalty held until pay failed or patrons fell. The ghulams’ obedience was transactional but not shallow. Betrayal required calculation. When it came, it was decisive.

Afterlives and Echoes

As Seljuk authority fragmented, ghulams did not disappear. They migrated into successor states, lent their expertise to new masters, helped birth later systems that refined the same logic. The Mamluk Sultanate would perfect what the Seljuks industrialized. Continuity lives in method.

Myths linger. Songs praise nameless riders. Chronicles inflate numbers. Oral traditions polish cruelty into courage. Modern historians argue footnotes while the core remains ugly and effective. The Seljuk ghulams were not an aberration; they were a solution that worked too well.

Their downfall was diffusion. As pay faltered and politics fractured, the system bled coherence. Individuals rose, units broke, loyalties reattached. The brotherhood thinned into memory and method. What endured was the idea that you could buy a man, teach him a god and a wage, and ask him to hold the line while empires rearranged themselves.

The dust settles where systems end. Ghulams left no homeland to mourn them, only a template that kept getting reused.

Notable Members

Alp Arslan (c. 1029–1072). Sultan, patron, and gambler with armies. He understood ghulams as tools that cut clean when sharpened properly. His campaigns leaned on their discipline while tribal forces roared around them. Chroniclers paint him pious; the field reports show a man who liked systems that worked.

Nizam al-Mulk (1018–1092). Vizier with ink-stained hands and a keen eye for steel. He married bureaucracy to ghulam force and kept the engine running longer than it deserved. His assassination proved the danger he managed so well. The system survived him; it also learned to fear knives in crowds.

Qutalmish ibn Arslan Yabghu (d. 1063). A Seljuk prince whose ambitions collided with the realities of disciplined troops. Ghulams followed orders, not bloodlines, and his defeat taught a generation what loyalty had become. His death cleared a path others marched through.

Tutush I (d. 1095). Ruler in Syria who inherited ghulams and the problems they solved. His reign shows the thin margin between command and collapse when pay falters. The units stayed lethal; the state did not.

Atsiz ibn Uwaq (d. 1078). A commander whose career illustrates upward mobility within the system. He leveraged ghulam discipline into regional power before being crushed by larger gears. The rise was real. The fall was instructional.

Bibliography

Bosworth, C. E. The Ghaznavids: Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran 994–1040. Edinburgh University Press.

Cahen, Claude. The Formation of Turkey: The Seljukid Sultanate of Rūm. Longman.

Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates. Pearson.

Peacock, A. C. S. The Great Seljuk Empire. Edinburgh University Press.

Al-Bundari. The History of the Seljuks. Translated selections.

al-Qalqashandi. Subh al-A‘sha. Volume containing administrative notes, marginalia.

Anonymous. Ledger of Horses That Remembered Too Much. Imperial Archive Shelf That Does Not Exist.

They left behind no clan songs, only the quiet certainty that disciplined violence outlives the hands that first bought it.