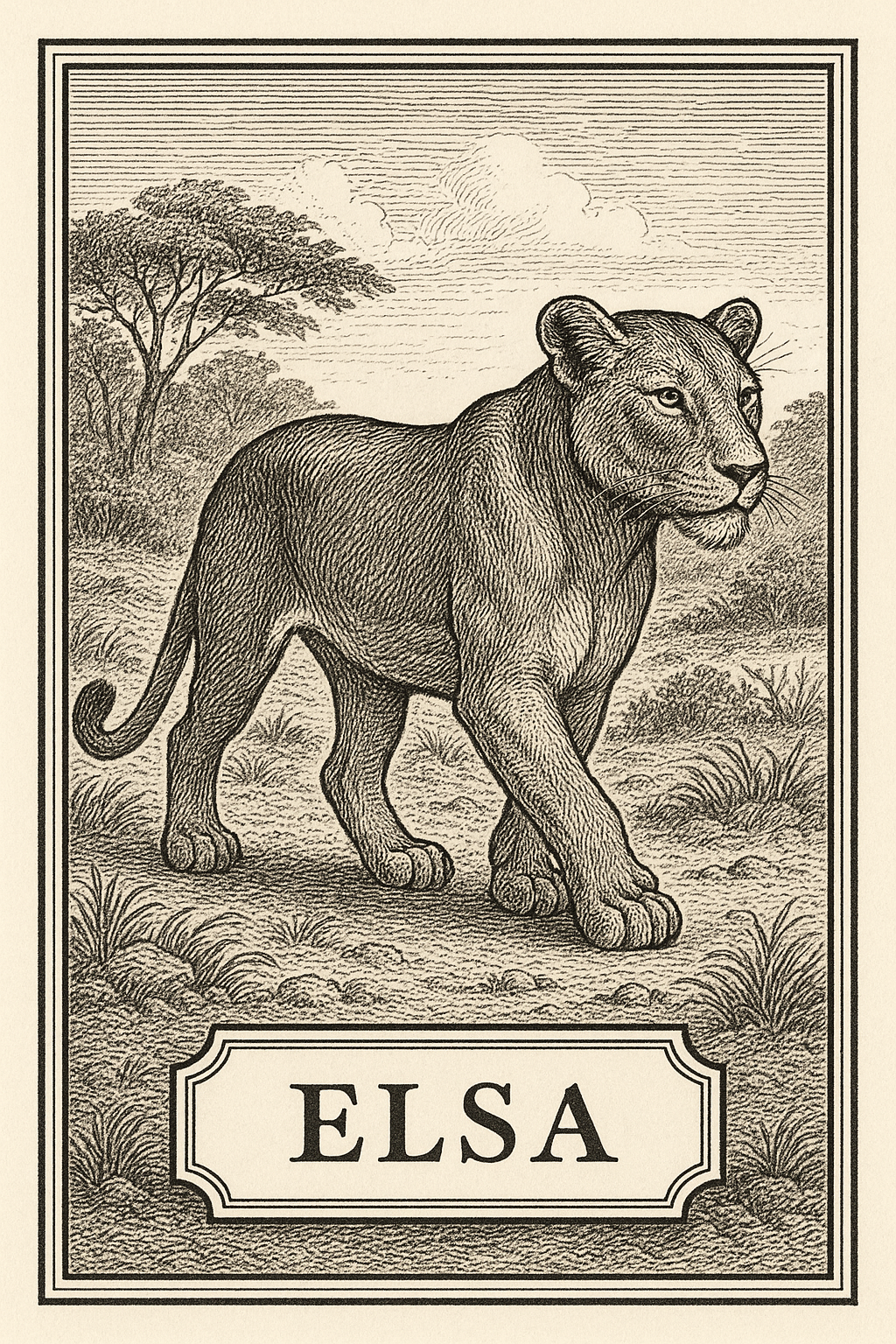

Elsa

The cub who learned freedom from the people who took it.

Meru National Park, Kenya — 1956. The light fell in long, amber ribbons across the scrub, the kind of light that convinces people they’re part of something eternal. Joy and George Adamson were parked in a Land Rover, watching three lion cubs roll in the dust beside their dead mother — shot after charging at them when they came too close. The couple loaded the cubs into the back seat, drove home, and began the most famous wildlife experiment since Noah. Two of the cubs would go to zoos. The smallest, a female, stayed. They named her Elsa. She grew up in a house — bottle-fed, leash-trained, loved like a child. Joy painted her portraits. George documented her growth in field notes written with the same bureaucratic tone used for oil inventories. Elsa slept in their bed, rode in the Land Rover, and learned to pounce on pillows instead of gazelles. The neighbors found it charming until she got bigger. A 300-pound lioness is difficult to describe as a pet, even when it purrs. The local game department suggested relocation, which was the polite term for “shoot it before it eats a tourist.” Joy refused. She decided to teach Elsa how to be wild again. Rewilding wasn’t a word yet, but the process was part heartbreak, part field study, and mostly improvisation. The Adamsons moved Elsa to Meru, living out of tents while George tried to teach her to hunt. The first attempts went poorly. Elsa stalked prey with enthusiasm and zero strategy, baffled that dinner ran away. She preferred to nap beside the Land Rover until George shot an antelope and pretended she’d done it herself. But over months, instinct began to override upbringing. She killed her first gazelle alone, then another, and another. By 1958 she was ranging farther each week, sometimes vanishing for days. Joy cried in her diary, calling it “the education of a child who must forget her parents.” Elsa eventually stopped returning at all. The Adamsons told themselves this was success — freedom as the goal, even if it looked like abandonment. In 1960 Joy published Born Free, her memoir of raising and releasing Elsa. The book became a phenomenon: a bestseller, then a film, then a cultural movement that made conservation fashionable for the first time since colonialism made it necessary. Tourists came to Kenya not to shoot lions but to atone for shooting lions. The theme song won an Oscar. Joy and George became global icons, though neither had much idea what to do with fame. Elsa reappeared briefly that same year, bringing her own three cubs to the Adamsons’ camp. It was the reunion scene no writer could have scripted better — Joy weeping, George astonished, the lioness watching with the patient confusion of someone visiting her childhood home and finding it smaller than she remembered. A few months later, she was gone again. Rangers found her body near the Tana River in 1961, dead from tick-borne disease, ribs showing through her coat. George buried her where she fell and placed a simple wooden cross over the grave. Her story never died. Joy was murdered by a former employee in 1980; George was killed by poachers nine years later. The Adamsons became martyrs of their own myth — patrons of the uneasy faith that love could civilize the wild without erasing it. Elsa, meanwhile, stayed frozen in film reels and classroom posters: the lioness who walked away and somehow forgave us for making her.