Judy

The only dog officially listed as a prisoner of war — and the best-behaved one.

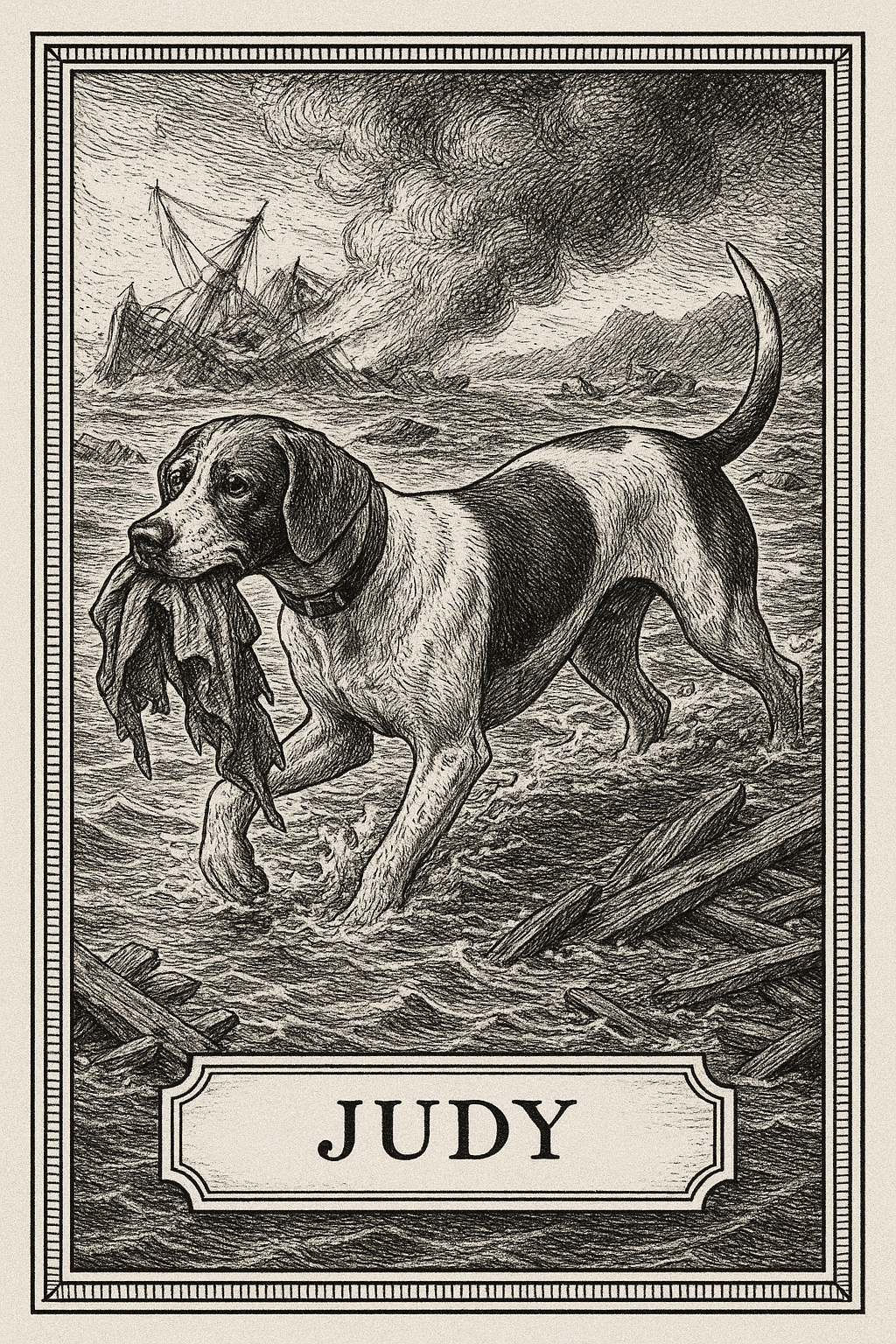

February 1942, the South China Sea — the HMS Grasshopper lay shattered and burning, struck by Japanese bombers during the fall of Singapore. Survivors clung to wreckage in oil-slick water, listening to the hiss of steam and the distant drone of planes circling back. Somewhere amid the chaos, a white-and-brown English pointer swam through the debris, barking hoarsely. Her name was Judy. She was the ship’s mascot — unofficial rank, morale unit, expert in biscuits. That day she saved several sailors by dragging them toward floating rafts, her teeth clenched in their sleeves. When the gunfire stopped, she paddled toward Sumatra with the others, the sea around her glittering with wreckage and the smell of fuel.

Judy had already lived one naval career before disaster. Born in Shanghai in 1936, she’d been adopted as the Grasshopper’s companion animal, trained to bark whenever planes approached long before radar did. The men fed her scraps, taught her tricks, and considered her part of the crew. When the ship went down, she behaved accordingly: duty first, panic later. After days adrift, the survivors made landfall on Sumatra, half-starved and hunted by enemy patrols. Judy led them to a freshwater spring — the difference between dying and walking another day.

Eventually, the group was captured. The Japanese guards herded them into Gloegoer Prison Camp near Medan. The pointer was smuggled in under a blanket and registered under an inmate’s number — a bureaucratic accident that made her, quite literally, a prisoner of war. Conditions were starvation-level. Guards beat men for hoarding rice. Judy scavenged rats, guarded rations, and once lunged at an officer who struck a prisoner. She took a bayonet to the shoulder for her trouble. Her handler, Leading Aircraftman Frank Williams, cleaned the wound with contraband rum and wrapped it in cloth torn from his own uniform. From then on, she never left his side.

Over three years, Judy became the camp’s heartbeat. She warned of approaching guards, comforted the dying, and distracted men from the sound of executions in the yard. Williams taught her to salute, to sit during roll call, to avoid stealing food in plain sight. When prisoners planned an escape, she carried notes hidden in her collar. When morale collapsed, she nuzzled the ones who’d stopped speaking. Men wept into her fur and called her “the only creature here who still believes we’re human.”

In 1944 the POWs were shipped to Singapore aboard the SS Van Warwyck, a freighter pressed into service as a prison ship. Halfway through the voyage, it was torpedoed by a British submarine unaware of its cargo. Judy was trapped below deck, locked in a galley compartment. Williams dove into the flooding hull, broke her free, and pushed her out through a porthole. They swam together through oil and fire until a passing vessel pulled them out — their second shipwreck together, and her third near-death.

When Japan finally surrendered, Judy returned home with Williams, gaunt but alive, with shrapnel scars in her shoulder and a military résumé that would shame most officers. She received the Dickin Medal — the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross — “for magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese prison camps.” The citation was written in neat typewriter script, careful not to mention the part where she’d bitten a guard.

Williams adopted her formally and brought her to England. She slept under his bed, barked at thunder, and never quite adjusted to peacetime. Crowds followed her at parades. Newspapers printed her photograph beneath headlines that called her “The Dog Who Fought Japan.” In 1950 she died quietly in Tanzania, where Williams had taken work. He buried her under a tamarind tree and placed a small bronze plaque on the grave: “Faithful companion, fearless friend.”