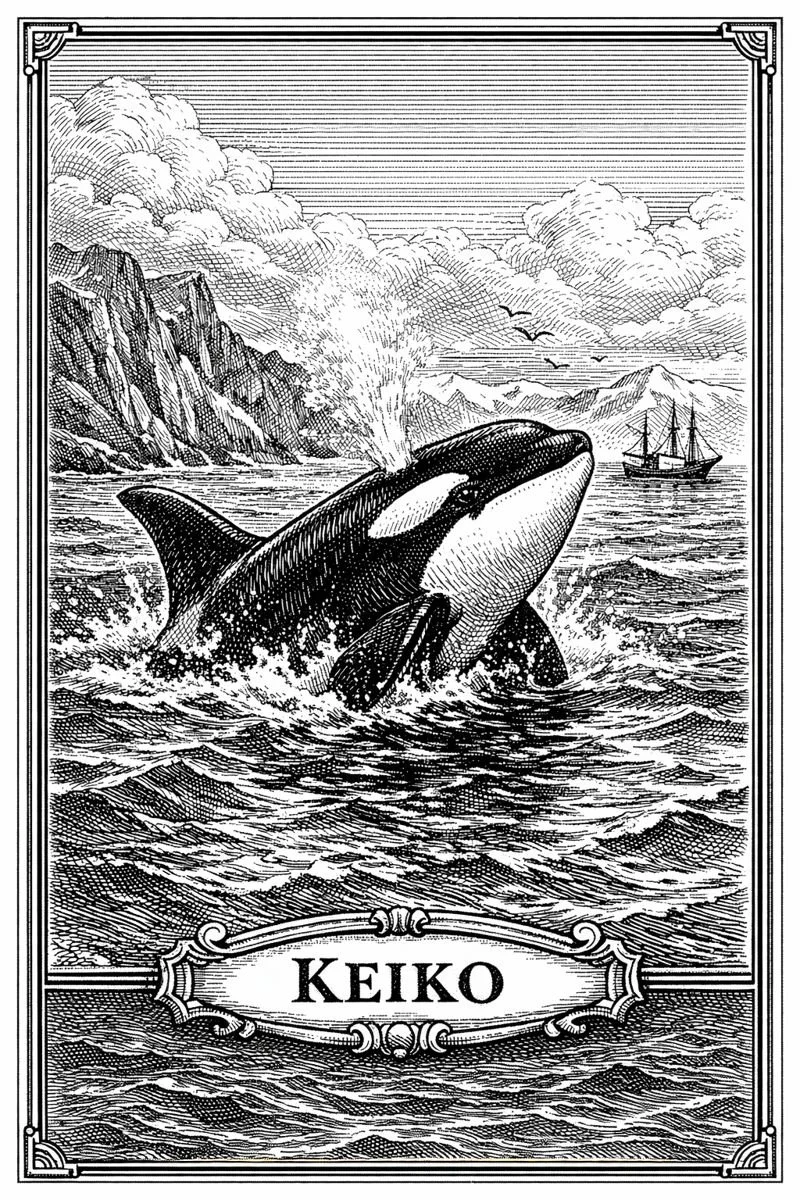

Keiko

The captive orca who swam home and couldn’t stay.

September 9, 1998 — Klettsvik Bay, Iceland. The water was cold and clean, heavy with rain and salt. For the first time in twenty years, Keiko felt the open sea beneath him. His black-and-white body — twenty-two feet long, six tons of muscle — moved without walls for the first time since capture. He surfaced once, twice, exhaled through the blowhole, and disappeared into the gray.

He’d been taken from Icelandic waters in 1979, sold to marine parks in Canada, Mexico, and finally immortalized in a movie — Free Willy, the story of a captive whale who leaps to freedom. The irony never left him. After the film, audiences learned the real whale was still confined, floating in a chlorinated pool in Mexico City. Donations poured in; corporations pledged redemption. Keiko was flown across continents on a cargo jet, a public act of penance.

For years, trainers prepared him for the wild — frozen fish instead of hand-fed, ocean sounds instead of applause. They taught him to chase live herring, to echo the calls of wild pods. Each lesson ended the same way: he would turn, expecting reward, the faint trace of dependency that captivity leaves behind.

In 2002, he made the journey north and left his handlers behind for good. He swam two thousand miles along the Norwegian coast, surfacing near fishing boats, following children’s laughter into harbors. Locals fed him cod and rubbed his rostrum. He was free, technically, but not wild.

That winter he died of pneumonia in a fjord near Halsa. Fishermen buried him by the shore, marking the grave with stones. The project that had cost millions ended in a quiet, natural death — the kind his kind rarely got.

They called it both a failure and a miracle. He had made it home, but home had changed without him.