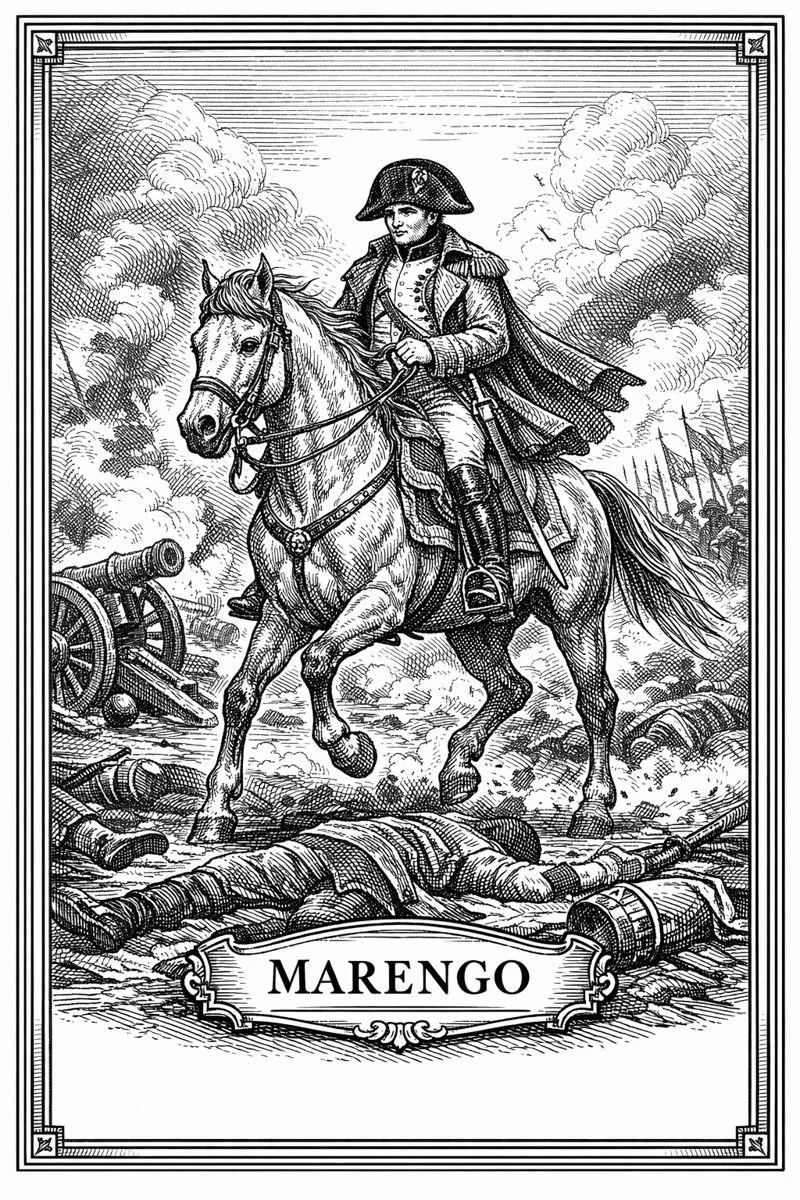

Marengo

Napoleon’s horse who outlived the empire he carried.

June 14, 1800 — near Alessandria, northern Italy. The battlefield at Marengo was soaked with dust and blood, and through it came a small gray Arabian stallion, ribs showing, coat foamed with sweat. On his back rode Napoleon Bonaparte, twenty-nine years old, uniform caked in powder, victory still uncertain. The horse moved like smoke, weaving through cannon fire, stepping over bodies as if born to it.

He had been imported from Egypt, part of the spoils of another campaign. They named him Marengo after the battle that sealed Napoleon’s legend. From then on, he carried his rider through Austerlitz, Jena, Wagram — a constant shadow beneath history’s heaviest boots. He was not fast, nor large, but steady, enduring, the sort of horse that survived what greatness demanded.

When the tide turned, he carried the emperor through the retreat from Moscow, ribs visible under the frost, lungs burning with the cold that killed men by the thousands. At Waterloo, he stood waiting while the empire ended under rain and artillery. When the French line broke, he fled with Napoleon into the smoke, the last loyal witness to defeat.

Captured by the British at the end of the campaign, he was taken across the Channel — a trophy, a relic, a prisoner. He lived quietly on an English estate for seventeen more years, chewing foreign grass under foreign skies. His hooves were trimmed for display; his skeleton later mounted at the National Army Museum in London.

The plaque beneath him reads: “Marengo, the Emperor’s Horse.” It does not mention the sound of muskets, or the frost that burned his nostrils, or the steady heart that kept pace with ambition until it outlived its master.