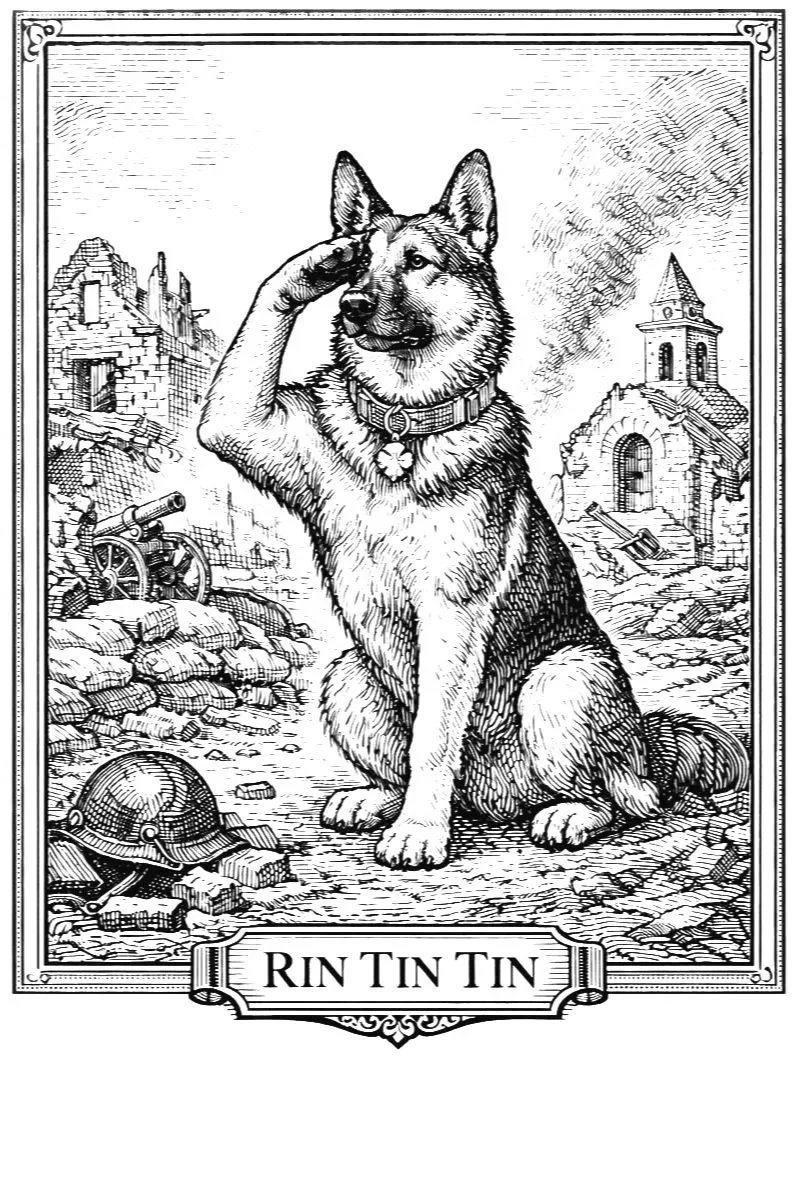

Rin Tin Tin

The war orphan who taught Hollywood how to salute.

September 1918 — Lorraine, France. The village was rubble, the air still thick with cordite. In the ruins of a bombed kennel, an American soldier named Lee Duncan found a litter of German Shepherd pups — five alive, their mother dead beside them. He took two back to the base, a male and a female. He named the boy Rin Tin Tin, after the French good-luck charm worn by soldiers for protection.

When the war ended, Duncan brought him home to California. He trained him in obedience, agility, and patience — virtues the trenches had made scarce. The dog learned everything: to leap walls, fetch messages, fake death. A film crew saw a demonstration, and soon the former war orphan was leaping from silent reels onto cinema screens.

By the mid-1920s, Rin Tin Tin was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars — the canine that saved Warner Bros. from bankruptcy. He performed his own stunts, out-earned his human co-stars, and received tens of thousands of fan letters. Children saluted him; soldiers wrote that he reminded them what loyalty looked like.

He was trained for applause, but never forgot the command come. Between takes, Duncan brushed his coat and whispered in French. When the cameras stopped, the dog still followed. Fame made them both rich and restless. Duncan once said, “He believes I hung the moon,” and it was true in both directions.

Rin Tin Tin died in 1932, on a quiet afternoon at home in Los Angeles, his head resting in Duncan’s lap. The radio announced his death like that of a statesman. He was buried in Paris, at the Cimetière des Chiens, under a marble marker worn smooth by hands.

On the screen, his successors kept his name alive — generation after generation reenacting the same loyalty. The real one had no script. He was a soldier’s souvenir who became the motion picture of devotion itself.