Machli

The queen who taxed her kingdom in blood and camera fees.

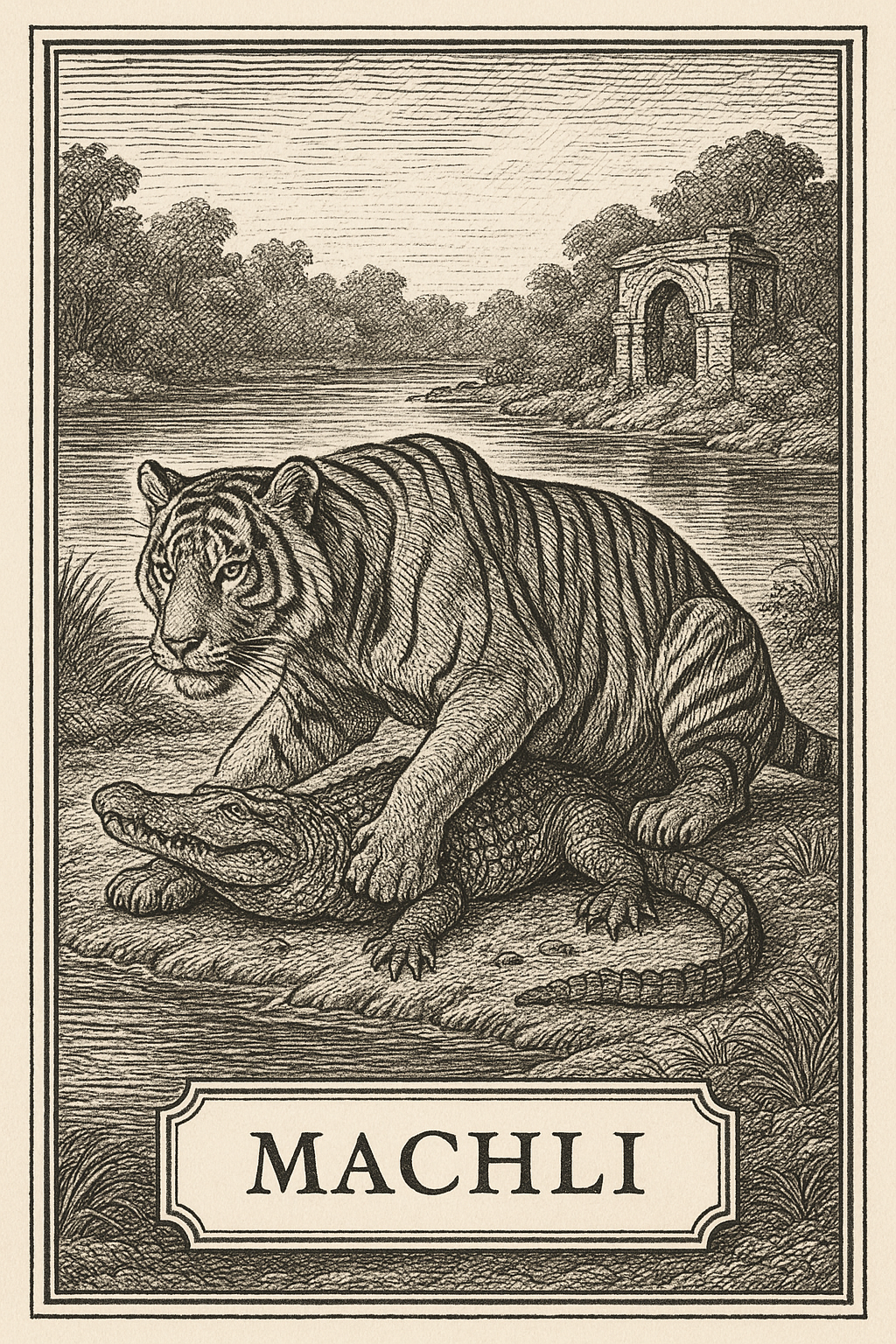

Ranthambore National Park, Rajasthan — dawn, May 2003. The lake was still, the air heavy with rot and monsoon breath. A ripple cut the surface: a mugger crocodile, thick as a log and twice as patient. On the bank, a tigress crouched, eyes steady, shoulders coiled like drawn bowstring. The tourists thought they were about to witness nature’s balance. They were about to watch a coup. When the crocodile lunged, she met it halfway, jaws closing on scaled armor, dragging it to shore. The fight lasted fifteen minutes. The tiger won. The crocodile became a footnote. Machli—the “fish-eyed” tigress—had just secured her throne.

She was born around 1996, daughter of Ranthambore’s reigning female, and inherited her mother’s kingdom the way most rulers do: by surviving long enough to be feared. Her territory spanned the lakes and ruins of the old fort—stone steps, banyan roots, the ghost of empire. Tourists came for her as much as for the architecture. She raised cubs under the broken arches of temples and hunted deer across ancient courtyards. Her presence alone funded an entire conservation economy; one tiger sustaining a village, a bureaucracy, and a myth. Guides called her Lady of the Lake. Scientists called her T-16. Locals called her money.

Machli understood ownership in a way economists would envy. She fought rivals, drove off her own offspring, and hunted with the arrogance of royalty. When park officials tried to track her, she learned the sound of their Jeeps and vanished into brush until she felt like being seen again. Photographers built careers on her patience. Magazines called her “the world’s most photographed tiger,” which was true, if you ignored how little she cared about the cameras. She tolerated their noise like a monarch tolerates applause—necessary, boring, beneath her.

For years she ruled uncontested. Her daughters and granddaughters inherited the park’s prime territories, spreading her bloodline across northern India. Poachers stayed away; killing her would have meant war with both the government and the global tourist market. Her image appeared on postage stamps, conservation posters, and grant proposals. She became an industry—proof that the living could be more profitable than the dead. The park credited her with bringing in over ten million dollars in tourism revenue. Machli never saw a rupee.

By the end, she was blind in one eye, missing two canines, and moving slowly but without surrender. Rangers found her scavenging near the park’s edge, half-starved, regal even in decay. They expanded her protected zone so she could die comfortably—a state pension, tiger edition. In August 2016 she lay down near a dry streambed she’d crossed a thousand times and didn’t get up again. The rangers cremated her with full Hindu rites: incense, marigolds, the kind of ceremony reserved for deities and dignitaries. The ashes scattered into the soil of a kingdom that had already begun to forget what silence sounded like.

Her descendants still patrol the same ruins. Tourists still whisper her name through telephoto lenses, hoping for a glimpse of something equally divine.