Buffalo Soldiers

(1866-1890)

Great Plains • Southwest Frontiers

Brotherhood Rank #190

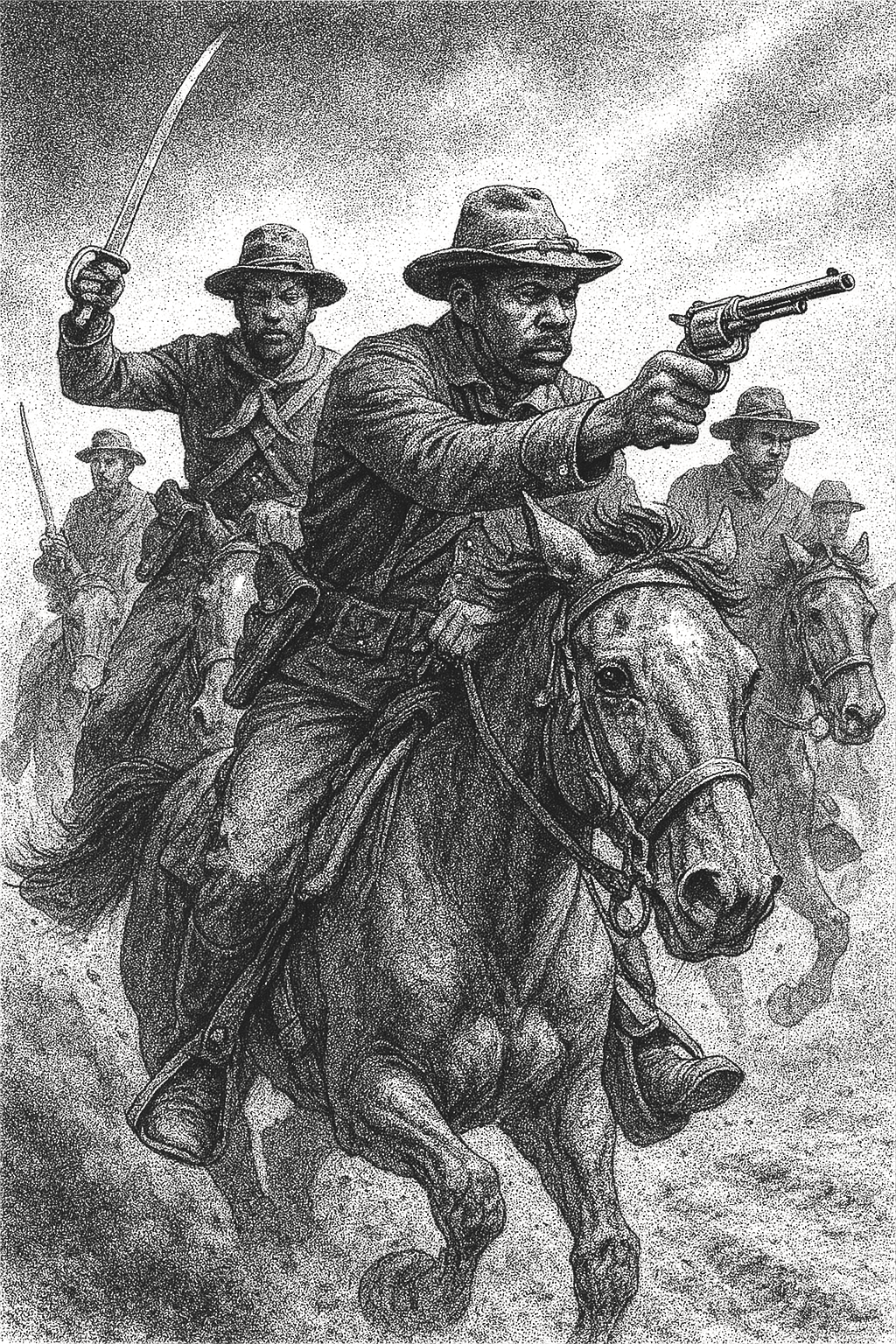

They rode into the smoke before anyone agreed whether the land ahead was a frontier or a graveyard. Hooves hammered through dust thick enough to chew, carbines slung low, sabers useless weight against the saddle, and the wind carrying that quiet warning the prairie gave right before it bared its teeth. The men of the 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry didn’t move like new regiments—they carried themselves with the grim assurance of people who’d already survived a country that barely wanted them alive. The noise of the march said all of it: discipline at the edges, violence beneath, and a slivered patience that snapped fast if pushed.

Somewhere ahead, a war party moved—Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne—names the officers whispered like weather reports. The troopers didn’t need the details. They looked into the blank horizon, reading it the way other men read Scripture: the sudden darkening of the sky, an unnatural stillness in the grass, a hawk spiraling low. They knew the difference between quiet and ambush like they knew the taste of ration coffee or the weight of disrespect in a white officer’s voice. Embers of old battles followed them. Shiloh. Appomattox. The last places they’d fought under a flag that promised much and delivered thinly.

But on this day, the promise didn’t matter. The regiment had a job, and men who had been denied everything tend to cling hardest to the one thing they’ve earned: their skill. When the first shots cracked from the ridgeline, they didn’t break. They rotated as a single mind—reins pulled tight, horses stomping, carbines sliding into palms slick with sweat. The reports came fast: one wounded, none down. A good start. The veterans of the 10th moved with a precision that suggested resignation and defiance wrapped together. The 9th advanced in long, controlled bursts, dust rising around them like a curtain meant to hide their intentions.

The frontier had its own physics. Distances lied. Shadows moved. Enemies vanished into draws so shallow you could step across them. The Buffalo Soldiers learned to fight in those illusions, riding until their thighs ached and their lungs rattled, sleeping light, waking fast, forming up at the slightest tremor in the air. Their knives were tools first, weapons second. Their carbines smelled of oil and grudges. Their discipline—well, that was a contested thing. Sometimes ironclad, sometimes furious, sometimes held together by little more than spite. But it was always enough.

By nightfall, the fight had burned down the way frontier fights often did—silent, scattered, resolved at distances too great to read the faces of the dying. They gathered the wounded, checked the horses, counted off quietly. A few officers congratulated themselves. The enlisted men, Black men who had bled at the birth of their own citizenship, just stared at the horizon. Tomorrow the winds would shift. Tomorrow the stories would twist. But tonight, they had lived. And that was the first oath of the brotherhood: ride, fight, endure.

Not for the nation that doubted them.

Not for officers who misused them.

But for the man on the horse next to them—

the one who knew what it cost to stay.

THE MAKING OF A BROTHERHOOD

The 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry were born out of political half-measures and racial fear: Congress wanted loyal, disciplined troops for frontier control but balked at granting Black veterans equal standing. So they split the difference—Black enlisted ranks under mostly white officers—and expected the experiment to fail. It didn’t.

The regiments recruited some of the toughest men in postwar America: former enslaved men who learned survival the hard way; veterans hardened in the Union ranks; freedmen searching for wages and dignity; wanderers who understood that a horse, a carbine, and a steady contract were more stability than they’d ever been offered. The result was a fighting force shaped by hunger, experience, and the relentless need to prove itself in a nation designed to erase their contributions.

From day one, they trained brutally: long drills on open plains, weapon maintenance to forensic perfection, horsemanship that bordered on obsession. Horses mattered more than half the officers—mounts were partners, warning systems, lifelines. A horse that faltered meant a man who died. So the 9th and 10th became master horsemen, capable of silent night movements that startled veteran scouts.

Their discipline wasn’t blind obedience—it was a shared stubbornness. They didn’t work hard because a lieutenant barked orders. They worked hard because failure meant handing ammunition to racists who demanded proof that Black soldiers couldn’t perform. That slow pressure bled into the culture: a constant, bitter insistence on competence.

PSYCHOLOGY OF THE BROTHERHOOD

They operated like a collective under siege.

Not from Comanche arrows or Apache lances—

from the Army itself.

When white officers ignored casualties or botched reconnaissance, the enlisted men compensated. When supply dumps shorted them food, they rationed better than any contemporary unit. When their valor was rewritten to minimize their impact, they built camaraderie out of silence: the understanding that their real record lived only between them.

The Buffalo Soldiers learned to trust each other absolutely, and trust officers selectively. Some leaders earned respect—Benjamin Grierson foremost among them. Others were tolerated. Others resented. But the unit never let internal bitterness crack their field performance.

TACTICS, FORMATIONS, AND KILL-PATTERNS

The frontier demanded adaptation. Traditional cavalry charges were theatrical nonsense against mobile Native forces who out-rode, out-scouted, and out-maneuvered nearly every regiment in the Army. So the 9th and 10th adopted hybrid tactics:

Mounted advance, dismounted firefight: closing distance fast, then fighting on foot with pivoting skirmish lines.

Extended pursuit work: long-distance chases requiring stamina few white regiments could match.

Night marches: disorienting for foes unused to mounted movement after sundown.

Small-unit initiative: sergeants making decisions that captains were too slow to issue.

Their lethality came not from overwhelming firepower but from durability. They outlasted. They tracked. They advanced through terrain others avoided. When forced into close combat, their discipline held. When hit with ambushes, they absorbed the shock and reformed rapidly, something Western scouts remarked on with genuine surprise.

LOYALTY AND RUTHLESSNESS

The Buffalo Soldiers carried the double burden of being both indispensable and undervalued. Loyalty ran horizontally, not vertically. Enlisted men followed each other first, the regiment second, the Army a distant third.

Were they ruthless?

When required.

They fought hard, and sometimes harsh. Frontier warfare blurred lines—retaliatory raids, burning encampments, capturing horses, denying resources. When given orders to pursue hostile bands, they did so relentlessly. The Army’s strategy included tactics modern audiences grimace at: forced relocations, punitive expeditions, destruction of winter food stores. The 9th and 10th executed these operations as any federal cavalry unit did. Their duty did not absolve them, but it places them squarely in the machinery of 19th-century American expansion.

They were not saints.

They were soldiers.

And soldiers follow campaigns that history later reevaluates through clenched teeth.

BATTLES AND DEFINING MOMENTS

The Battle of the Mimbres Mountains, Red River campaigns, escorts through Mescalero and Apache territories, brutal winter marches in Wyoming and Kansas—none were grand spectacles, but they forged a reputation: regiments that didn’t break, didn’t complain, and didn’t lose horses unnecessarily. Their fight at Beecher Island, though indirect, still shaped perceptions of their reliability. At Fort Robinson and Fort Supply, they held lines others struggled to maintain.

Their most famous engagement of the frontier period wasn’t a “big” battle—it was the endless chain of small ones: ambushes thwarted, scouts rescued, stage lines protected, settlers escorted, raids countered. No glory, little recognition, but a steady accumulation of proof: these men were among the most effective cavalry the U.S. Army fielded in the 19th century.

RESPECT EARNED—RELUCTANTLY GIVEN

Native opponents respected their tenacity.

White officers respected their results.

The Army respected their statistics.

The public rarely respected them at all. Newspapers often failed to mention them or attributed their successes to white officers. But frontier commanders—those who bled out there—knew the truth. The 9th and 10th were among the few regiments you wanted on the line when the world went sideways.

THE FRONTIER PERIOD CLOSES

By the 1890s, the frontier was collapsing under its own mythology. The Buffalo Soldiers shifted from pacification to patrolling borders, quelling violent disputes, and enforcing increasingly political policies. Their legacy was already complicated: loyal service to a country that degraded them; participation in campaigns that crushed Indigenous resistance; a warrior culture forged through hardship and contradiction.

Their frontier story is one of grit, skill, injustice, endurance, and the sharp-edged truth that duty rarely aligns with righteousness.

They rode anyway.

NOTABLE MEMBERS (W.I.A. STYLE)

Sergeant Emanuel Stance (1843–1887)

A relentless fighter with a temper that rode just ahead of him, Stance earned the first Medal of Honor awarded to a Buffalo Soldier for a violent running battle near Kickapoo Springs. He led from the front, not because doctrine demanded it, but because he refused to let anyone say a Black sergeant hid behind his men. Stance was brilliant, abrasive, and impossible to ignore—qualities that made him indispensable in the field and difficult in barracks. His reputation for aggression wasn’t bluster; it was muscle memory carved from a lifetime of fighting for legitimacy.

First Sergeant Henry Johnson (1850–1904)

Johnson was the kind of cavalryman who turned chaos into order just by existing inside it. Cool under fire, sharper than most of the lieutenants assigned to him, he kept companies alive through judgment refined on forced marches and skirmish lines. His Medal of Honor came from courage, yes, but also from a stubborn refusal to let terrain, odds, or officers dictate outcomes. Men followed him because he never asked for anything he wouldn’t endure first.

Sergeant George Jordan (1847–1904)

Jordan built a reputation on endurance—long chases, nighttime advances, and holding positions that were supposed to collapse. At Fort Tularosa he turned a defensive stand into a story the regiment repeated for years, a testament to what a quiet, steady man could do with a rifle and a will that didn’t bend. His Medal of Honor recognized gallantry; the enlisted men recognized something deeper: a man who made the hard parts of soldiering look almost serene.

sources

Annual Report of the Secretary of War. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1870–1890.

Grierson, Benjamin H. The Records of the Tenth Cavalry. Washington: U.S. Army Archives, 1889.

Leckie, William H. The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Black Cavalry in the West. University of Oklahoma Press, 1967.

Schubert, Frank N. Voices of the Buffalo Soldier: Records, Reports, and Recollections of Military Life and Service in the West. University of New Mexico Press, 2003

Haynes, Robert V. The Buffalo Soldiers and the American West. Texas A&M University Press, 1990.

Holloway, R. M. An Unnecessarily Detailed History of Horses Who Judged Their Riders Harshly. St. Louis: Frontier Equestrian Press, 1911.