Egyptian New Kingdom Chariot Corps

(c. 1550–1070 BCE)

Nile Valley, Levant, Nubia

Brotherhood Rank #183

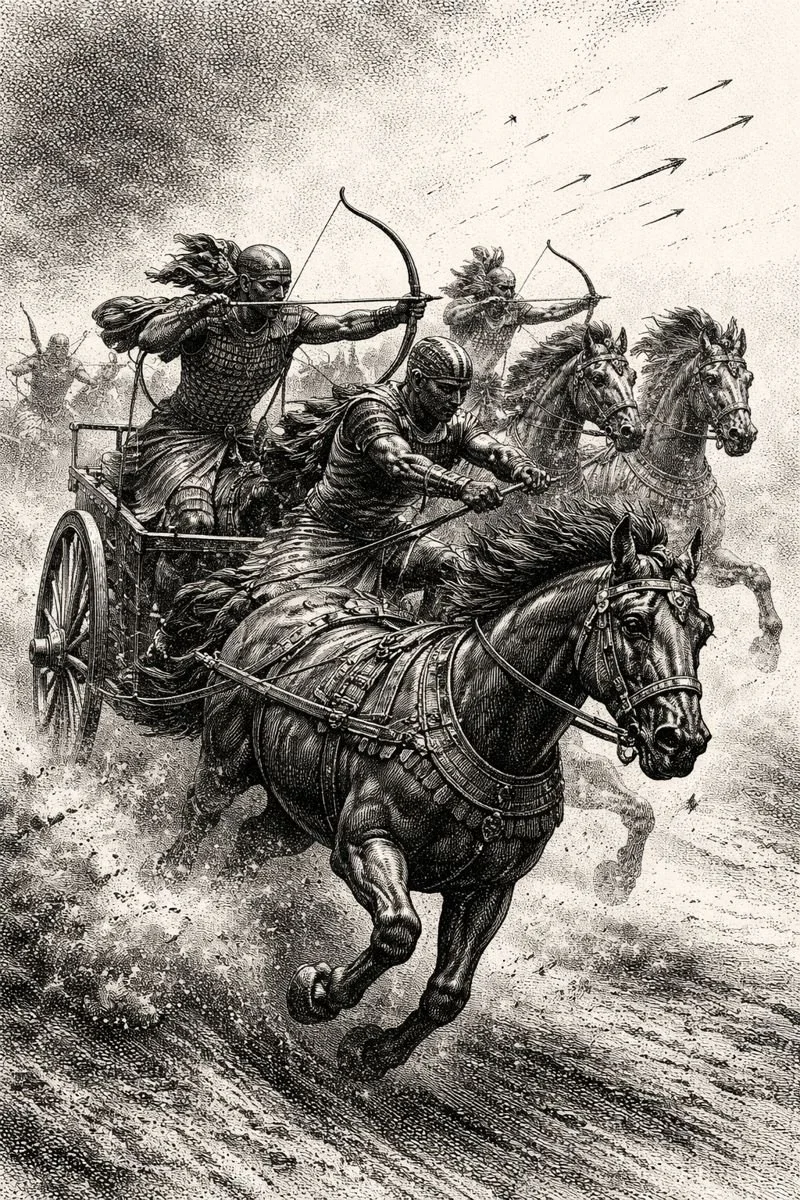

The dust arrives before the sound. It always does. A low brown veil rolling over the baked plain, lifting in sheets under hooves that never touch the earth long enough to apologize. Then the noise comes apart in layers: leather creaking, wheels screaming, horses breathing like bellows pushed past reason, men shouting short commands that are already obsolete by the time they leave the mouth. Bronze flashes. Feathers shake. The horizon fractures into motion.

This is not infantry war. This is speed weaponized. The New Kingdom chariot corps does not advance so much as rupture the day.

They come in pairs. Always pairs. One man with the reins, one with the bow. Balance over brute strength. Control over frenzy. The chariot is light, a bentwood skeleton stitched with rawhide and arrogance, small enough to dance, strong enough to kill kings. It skims, pivots, recoils, returns. The corps fights like a nervous system, firing signals faster than the enemy can understand them. Arrows fall not in volleys but in answers. A threat appears. The chariot is already gone, already somewhere else, already bending the battlefield into something unfamiliar.

Later scribes will carve them into stone as eternal victors, wheels frozen mid-spin, horses frozen mid-snort, enemies frozen mid-collapse. Reliefs do not show panic. They do not show missed shots. They do not show the corps turning back because the ground was wrong, the horses spooked, the lines tangled. But the dust remembers. The bones remember. And the chariot corps remembers itself as something more than decoration for temples. It remembers the first time speed decided an empire.

Egypt did not invent the chariot. It stole it, learned it, and then sharpened it until it fit the Nile like a blade fits a hand. The Hyksos had brought the technology centuries earlier, humiliating Egypt with mobility it could not answer. When the New Kingdom rose from that humiliation, it did so with a grudge, and the chariot became the argument that never needed to be repeated. Pharaohs stopped waiting behind walls. They went out hunting kingdoms.

The corps became the visible nerve of imperial ambition. Not peasants with spears. Not massed ranks chanting discipline. This was an elite culture on wheels, fed better, trained harder, buried with honors that suggested they had touched the gods by moving too fast for death to keep up.

They were not invincible. They were expensive, temperamental, and murderous only when everything worked. But when it worked, the world bent.

The New Kingdom’s chariot arm emerged as a solution to a problem Egypt could no longer ignore. Infantry could hold ground. Archers could bleed an enemy at range. Neither could decide wars across deserts, rivers, and foreign hills with speed. The chariot offered reach. It offered pursuit. It offered spectacle. Pharaohs needed all three.

Origins lie in adaptation, not revelation. Egyptian craftsmen stripped weight from Near Eastern designs, moved the axle to the rear for tighter turns, widened the stance for stability, and tuned the whole machine for open ground. Horses were imported, bred, and trained obsessively. This was not a farmer’s army. It was a state project with a logistical tail that ran from pasture to palace.

The men who rode were drawn from the elite. Sons of nobility, retainers of the court, warriors who could afford the time and risk. This shaped the corps psychologically. They were not anonymous. Names mattered. Reputation mattered. A charioteer’s failure echoed loudly, and success echoed longer. Reliefs and inscriptions name them. Tombs remember them. This visibility sharpened both courage and recklessness.

Training fused horsemanship, archery, and coordination until the pair functioned as a single organism. The driver was not a lesser role. He was survival. Control at speed over uneven ground while arrows hissed past demanded a calm bordering on coldness. The archer had to shoot accurately from a platform that refused to stay still, compensating for motion, wind, and panic. Together they created a moving killing field that punished anything slow enough to be noticed.

Discipline was real, though filtered through status. Punishment existed, but shame was often sharper than the lash. Cowardice in the corps did not just fail the state. It failed the image of the warrior aristocracy. Oaths bound them to pharaoh, but ambition bound them to each other. Glory was a shared currency.

On the battlefield, the corps behaved less like a wall and more like weather. They did not hold. They harassed, flanked, isolated, and pursued. Against infantry, they were predators, skirting the edges, firing into exposed backs and sides, breaking cohesion until foot soldiers forgot which way safety lay. Against other chariots, fights became duels of nerve and skill, wheels threading impossible gaps, arrows exchanged at terrifying proximity.

Kadesh remains the corps’ most famous trial by fire, largely because Egypt never stopped talking about it. The reliefs present a pharaoh alone against a sea of enemies, chariot charging heroically into history. The reality, reconstructed from Egyptian and Hittite sources, is messier. Egyptian chariot units were surprised, scattered, then rallied. They did not annihilate the enemy. They survived, regrouped, and fought their way out. It was not clean victory. It was institutional resilience under catastrophic error. The corps absorbed shock and did not dissolve. That mattered more than triumph.

Tactically, they relied on composite bows with bone and sinew, weapons that rewarded strength, technique, and maintenance. Arrows were armor-piercing enough to maim horses, men, and morale. Spears and axes existed for close work, but the chariot’s soul lived at range. Kill-patterns favored disruption over slaughter. A broken army died later, elsewhere.

Logistically, the corps was a constant headache. Horses required fodder and water in environments that offered neither generously. Chariots broke. Wheels warped. Leather dried and split. Campaigns demanded preparation bordering on paranoia. This vulnerability shaped strategy. Chariot warfare thrived on plains, roads, and valleys. Mountains and forests were negotiated reluctantly or avoided outright.

The corps’ relationship with brutality was pragmatic rather than sadistic. Prisoners were taken, paraded, and sometimes executed, often ritualized to reinforce royal authority. Mutilation of enemies appears in records, hands and phalluses counted as proof of kills, but these acts served bureaucratic accounting as much as terror. The chariot corps was an instrument of state violence, not a freelance horror show. That distinction did not make it kinder.

Respect followed them. Allies admired their speed and polish. Enemies feared the sound of wheels. Nubian campaigns saw chariots used to devastating effect against forces unused to such mobility. In the Levant, city-states learned to fortify and negotiate rather than meet them in open ground. The corps became shorthand for Egyptian power, its image exported alongside grain and gold.

Myth grew quickly. Pharaohs were shown personally driving chariots, arrows flying with divine accuracy. These scenes are propaganda, but not pure fiction. Kings did ride. They did train. Yet the corps was not a one-man show. Its effectiveness lay in coordination, repetition, and collective competence. The myth flattened this into hero worship, but the machine beneath remained visible to anyone who had stood near it while it moved.

Decline came quietly. Not with a single defeat, but with changing economics and enemies. Iron weapons spread. Infantry tactics adapted. Chariots remained potent but increasingly situational. The cost-benefit ratio worsened. States that could not afford chariot corps found other ways to fight. Egypt’s political fragmentation after the New Kingdom eroded the centralized support the corps required. Horses still ran. Wheels still turned. But the edge dulled.

By the time Assyrian cavalry perfected mounted warfare, the chariot was already aging into ceremony. It did not vanish. It transformed, lingering in ritual, memory, and art long after it stopped deciding wars. The corps faded not because it failed, but because war learned to move even faster.

The cultural afterlife of the New Kingdom chariot corps is enormous. It survives in stone, in textbooks, in the shorthand of “pharaoh on a chariot” as a symbol of ancient might. Modern retellings exaggerate its dominance, flatten its limits, and forget its fragility. Yet beneath the myth, the reality remains sharp. This was a brotherhood that taught empires to think in terms of speed, shock, and coordination. It made motion lethal.

Their legacy is not that they always won, but that after them, standing still became a mistake.

Notable Members

Ahmose I (c. 1550–1525 BCE)

Founder of the New Kingdom and inheritor of humiliation, Ahmose rode chariots not as theater but necessity. He fought the Hyksos with their own stolen tools and made the chariot a symbol of reversal. Sources suggest active participation in campaigns, though later inscriptions inflate his lone heroics. His reign welded technology to kingship and set the tone for centuries. He did not perfect the corps, but he made it inevitable.

Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BCE)

The most aggressive mind ever to sit behind Egyptian reins. Thutmose III used chariot units as surgical instruments, exploiting speed to fracture coalitions in the Levant. At Megiddo, his willingness to gamble on terrain showed a commander who trusted mobility over caution. Inscriptions praise divine favor, but patterns of maneuver reveal a ruthless professional. He turned the corps into an empire-expanding engine.

Amenhotep II (c. 1427–1401 BCE)

A king who boasted of strength and skill, Amenhotep II leaned hard into the image of the warrior-charioteer. Athletic displays and exaggerated claims surround him, some disputed by modern historians. Yet campaigns suggest competent use of chariot forces to suppress rebellion. He embodied the aristocratic warrior ethos that defined the corps’ culture. Pride was both his fuel and his flaw.

Ramesses II (c. 1279–1213 BCE)

The loudest voice in Egyptian stone. At Kadesh, Ramesses II survived disaster and turned it into legend, with the chariot corps as his supporting cast. Egyptian accounts center him alone, but the reality credits regrouped units and allied contingents. He understood propaganda as a weapon equal to arrows. The corps under him became immortalized, flaws and all.

Panehsy (fl. 13th century BCE)

A lesser-known chariot officer named in inscriptions, Panehsy represents the professional backbone beneath royal myth. Likely responsible for unit command and discipline rather than spectacle. Figures like him kept wheels turning and horses fed. History remembers kings, but men like Panehsy kept the corps alive. His obscurity is the point.

Resources

Ahmose, Son of Ebana. Autobiographical Inscription. New Kingdom primary source inscriptions.

Ramesses II. Battle of Kadesh Reliefs and Poem. Temple inscriptions at Karnak and Abu Simbel.

Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Spalinger, Anthony J. War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom. Blackwell Publishing.

Darnell, John Coleman. The Ancient Egyptian Warrior Culture. Yale University Press.

Hori, Scribe of Nowhere. How to Win a Chariot War Without Breaking the Wheels. Papyrus lost, footnotes suspicious, confidence unearned.