The Teutonic Knights

(c. 1190–1525)

Baltic Crusader State, Prussia, Livonia, Eastern Europe

Brotherhood Rank #182

They arrived on the Baltic shore like a legal document sharpened into a blade.

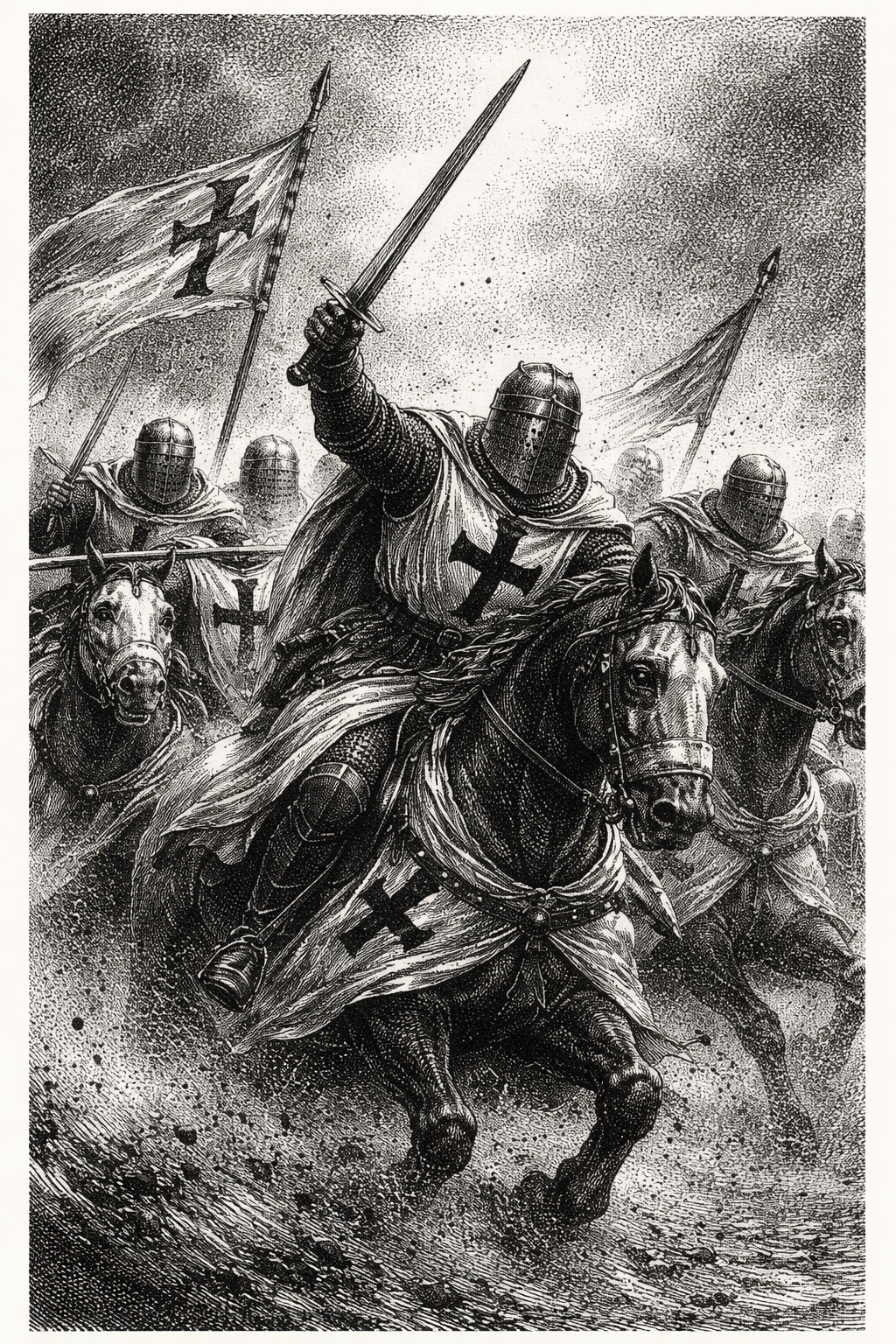

White cloaks stiff with salt and old vows snapped in the wind. Black crosses stark as a verdict. The horses sank fetlock-deep into wet sand while pagan watchfires flickered in the treeline, and somewhere inland a village was already rehearsing its burning. This was not pilgrimage anymore. This was a system moving into place.

Steel did not clatter. It moved with the quiet confidence of men who believed the paperwork was already done.

The Teutonic Knights did not ride in shouting. They rode in alignment. Saddles straight. Ranks closed. Silence enforced by habit rather than fear. Their violence was administrative, ritualized, audited. They did not hate the Prussians, the Lithuanians, the Samogitians, the Livonians. Hatred was inefficient. They converted or erased with the same steady hand, because the Order’s God preferred outcomes over emotion.

The cross on their chests was not a symbol of mercy. It was a logo.

They had been born far from this damp frontier, in the sun-bleached chaos of the Third Crusade, as a German hospital brotherhood tending the sick outside Acre. Caretakers first. Then guards. Then men who learned the easiest way to protect a hospital was to own the countryside around it. The Holy Land spat them back out after a century of failure, and the Order went looking for a place where crusade still paid dividends.

They found it in the north. Forests thick enough to swallow armies. Rivers that froze into highways. Tribes with no pope, no king, no Latin contracts to argue over. A blank ledger, waiting for ink.

Here, the Teutonic Knights did not just fight wars. They built war. Brick by brick. Charter by charter. Castle by castle. A military order that learned how to rule, tax, import settlers, regulate trade, and still ride out to slaughter at dawn.

They were monks who mastered siegecraft. Bureaucrats who perfected terror. Men who could hear confession at dusk and hang a village at dawn without feeling the contradiction itch.

This was not chivalry. This was colonization with absolution baked in.

The Order as Machine

The Teutonic Order functioned less like an army and more like a refinery.

Men entered stripped of family, inheritance, and softness. Three vows. Poverty that still allowed warhorses worth a barony. Chastity enforced with surveillance and punishment. Obedience that extended from battlefield maneuver to how long a candle burned in a dormitory.

Discipline was not inspirational. It was procedural.

Knights sat atop the hierarchy, noble-born heavy cavalry with mail and plate, but they were only the visible tip. Beneath them churned sergeants, half-brothers, priests, mercenaries, colonists, engineers, merchants, and enslaved labor. The Order recruited German settlers by the tens of thousands, reshaping the demographic spine of the Baltic coast while the sword cleared space.

Punishment was swift and internal. Breaches of discipline could mean flogging, demotion, expulsion, or imprisonment in castle cells that learned your breathing patterns. Chroniclers attest to severe internal justice, though details are often filtered through later moralizing lenses. What is not disputed is that cohesion mattered more than mercy.

This produced a collective psychology that prized endurance over brilliance. Individual heroics were tolerated only if they did not disrupt formation. The Order trusted repetition. Drill. Predictable lethality.

On the field, they advanced like a tide with armor.

Founding a State That Could Kill

Invited by Polish dukes in the early 13th century to subdue pagan Prussians, the Order immediately began renegotiating the invitation into ownership. Papal bulls and imperial charters followed. The Knights did not conquer land for others. They conquered it for the Order.

What followed was not a campaign but a century-long strangulation.

Prussian tribes were crushed in stages. Revolts flared and were drowned. Leaders were executed, sometimes ritually. Survivors were baptized, resettled, taxed, conscripted, or erased from record. Archaeology and chronicles align on the devastation, though casualty numbers remain debated. Entire cultures were extinguished with methodical efficiency.

The Order fortified everything. Marienburg rose on the Nogat River like a stone doctrine. Red brick castles spread across Prussia in geometric patterns, each a logistics hub, granary, armory, prison, and chapel. These were not romantic fortresses. They were infrastructure.

From these walls rode raids timed to seasons, frozen rivers enabling deep strikes into Lithuanian territory. Summer meant harvest and siege. Winter meant ice roads and surprise.

The Knights excelled at sustained pressure. They could lose men and replace them. Lose battles and still grind forward. They were less flexible than nomad enemies, but far harder to exhaust.

Their brutality was not exceptional for the era. What made it distinct was scale and persistence.

Battlefield Temperament

The Teutonic Knights fought like men who trusted armor and formation more than intuition.

Heavy cavalry charges anchored their doctrine, disciplined lances breaking enemy lines while infantry and auxiliaries secured ground. Against lightly armored Baltic warriors, the impact was devastating. Against steppe-style mobility, they struggled.

They preferred open ground. They disliked marsh and forest unless methodically cleared. When ambushed, they regrouped rather than scattered, often turning disasters into grinding withdrawals that still bled pursuers.

Their castles allowed them to lose tactically without losing strategically. A retreat did not mean collapse. It meant the enemy had to break teeth on walls.

Cruelty followed victory. Executions were common. Forced conversions enforced. Hostages taken. These acts served psychological warfare as much as punishment.

Enemies feared the Order’s refusal to negotiate once judgment had been passed.

Myth, Propaganda, and Self-Image

The Teutonic Knights wrote themselves as holy warriors on civilization’s edge.

Chronicles emphasized martyrdom, divine favor, and righteous extermination. Pagan resistance was framed as demonic stubbornness. Losses were trials. Victories were proof.

Modern historians note the propaganda density of these sources. Accounts of miraculous interventions, heroic last stands, and sanctified brutality often inflate the Order’s moral clarity while minimizing internal dissent and strategic blunders.

Yet myth mattered. It attracted recruits. It justified taxation. It smoothed the conscience of Europe’s donors.

The black cross became a brand recognized from Rome to Riga.

Cracks in the Armor

The Order’s greatest enemy was success.

As pagan neighbors converted or centralized, the legal basis for crusade thinned. Lithuania’s conversion to Christianity undercut the Order’s raison d’être. Wars continued anyway, now nakedly political.

At Grunwald in 1410, the machine broke.

Polish-Lithuanian forces shattered the Order’s field army. The Grand Master fell. The defeat did not destroy the Order immediately, but it cracked the myth. The Knights could bleed. Badly.

What followed was decline by accounting.

Indemnities drained coffers. Mercenaries demanded payment. Internal tensions rose between German elites and local populations. The castles still stood, but their meaning shifted from expansion to defense.

By 1525, the last Grand Master secularized Prussia, converting the Order’s territory into a duchy. The monk-knights became landlords. The crusade ended not in fire but in signatures.

The Order survived elsewhere in diminished, ceremonial forms. Its teeth were gone.

Cultural Afterlife

The Teutonic Knights linger as symbols more than soldiers.

In nationalist myth, they are alternately civilizers or monsters. In popular culture, their black crosses echo ominously, stripped of context, repurposed for aesthetic menace.

Historians continue to argue over their balance of brutality and governance. What is settled is this: they proved that holy war could be systematized into a state apparatus and sustained across generations.

They turned faith into logistics.

They built a kingdom that knew how to kill, and forgot how to stop.

The Teutonic Knights left behind brick castles, emptied forests, rewritten maps, and a lesson Europe would relearn repeatedly: that righteousness armed with paperwork can be deadlier than fury.

Notable Members

Hermann von Salza (c. 1170–1239)

Grand Master during the Order’s rise from obscurity to Baltic dominance. Diplomat as much as killer, he maneuvered papal and imperial politics with surgical precision. He understood that charters could conquer faster than swords if backed by both. Under his leadership, the Order secured legitimacy that outlived individual campaigns. He rarely appears blood-soaked in chronicles, which is precisely why his fingerprints are everywhere. Empires often begin with men who never raise their voices.

Ulrich von Jungingen (c. 1360–1410)

Grand Master at Grunwald, and the embodiment of the Order’s overconfidence. Brave, aggressive, and strategically rigid, he led the charge that broke the Knights against a united enemy. Killed in the fighting, his death marked the end of the Order’s illusion of invincibility. Chroniclers later tried to soften the failure with heroics. The battlefield did not cooperate.

Winrich von Kniprode (c. 1310–1382)

One of the longest-reigning Grand Masters, presiding over the Order’s territorial peak. Administrator, colonizer, and war manager rather than crusading romantic. He expanded fortifications and stabilized governance while keeping pressure on Lithuania. His reign shows the Order at its most efficient and least introspective. The machine hummed under his hand.

Albert of Brandenburg-Ansbach (1490–1568)

The last Grand Master in Prussia and the man who ended the crusade with a conversion. He secularized the Order’s lands, becoming Duke of Prussia and abandoning monastic rule. To some, a traitor. To others, a realist who read the balance sheet. He buried the sword and kept the land.

Resources

Peter von Dusburg. Chronicon Terrae Prussiae. c. 1326.

William Urban. The Teutonic Knights: A Military History.

Eric Christiansen. The Northern Crusades.

Alan V. Murray. Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier.

Norman Davies. God’s Playground: A History of Poland.

Brother Konrad’s Ledger of Perfectly Reasonable Executions, Vol. VII, allegedly misplaced behind the altar sometime after lunch.