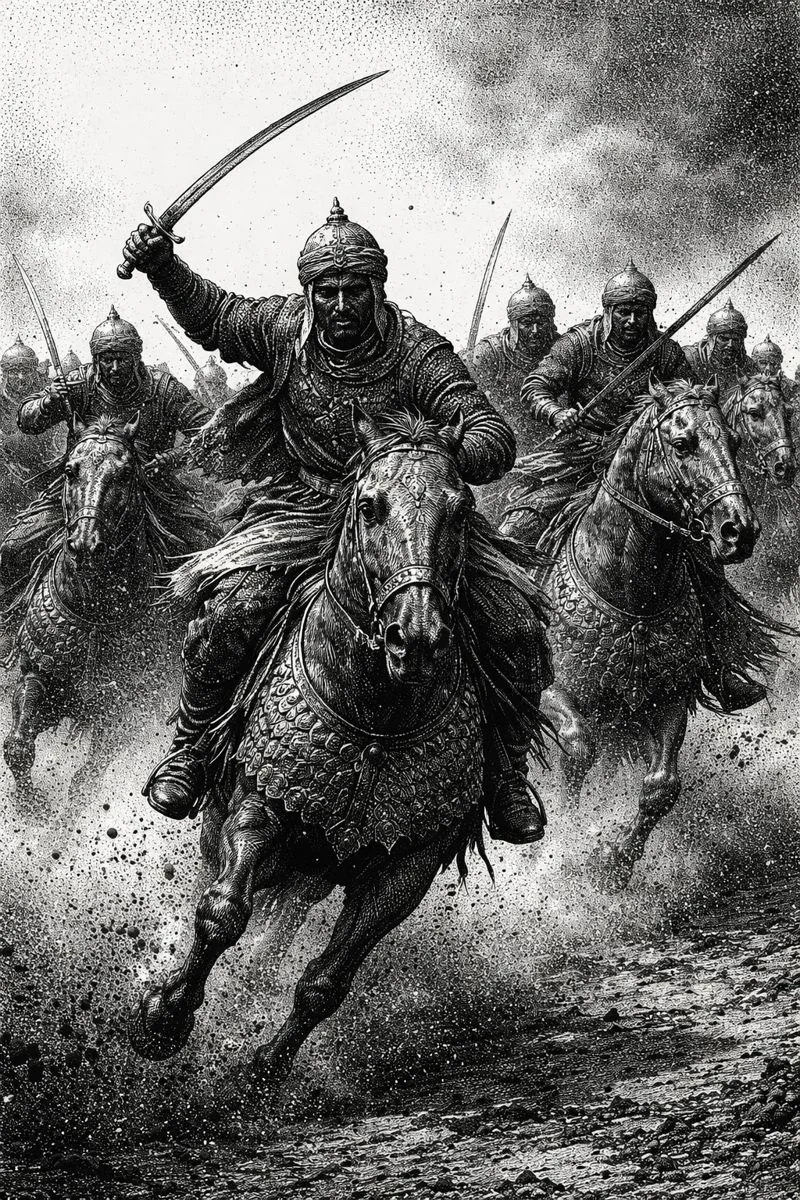

Fatimid & Ayyubid Mamluk Cavalry

(c. 909-1250 CE)

Egypt, Syria, Hejaz, Upper Mesopotamia

Brotherhood Rank #180

They come on horseback, not charging so much as arriving, a tide that has already decided the shoreline is guilty. Mail whispers. Lamellar ticks like teeth. The horses are compact, angry things with barrel chests and scabbed knees, trained to absorb shock and keep breathing. Above them ride men bought young, broken young, renamed young, their pasts erased and replaced with a geometry of drills and punishments. The lances dip and rise. The bows flex. A cavalry line folds and refolds like a living hinge, and the battlefield begins to accept a new grammar.

The first mistake is thinking of them as a unit. They were a system. They were a market that turned boys into weapons and loyalty into a currency. Under the Fatimids they learned how to be ornamented and lethal at the same time, riding in parades one week and cutting down Bedouin raiders the next. Under the Ayyubids they learned hunger, discipline, and how to survive a court where praise curdled overnight into exile or execution. Across dynasties, the Mamluk cavalry learned the same lesson again and again. Horses age. Sultans die. Steel endures.

They moved like a profession that expected to be hated. Their victories were efficient, rarely merciful, often misunderstood. Chroniclers admired their horsemanship and flinched at their cruelty. Poets gilded them. Jurists tolerated them. Peasants prayed they would pass through quickly. They were foreign-born defenders of Islam, enslaved soldiers who guarded caliphs, a paradox sharpened on whetstones imported from Damascus. When they rode, the ground learned to keep quiet.

The Fatimid court in Cairo dressed them first. White banners, black banners, green banners. Processions thick with incense and money. The cavalry learned to look like the state. Then the Ayyubids taught them how to break one.

Origins: Purchase, Conversion, and the Machinery of Obedience

“Mamluk” meant owned. Not metaphorically. Literally. Boys were bought from the Eurasian steppe and the Caucasus, Turkic speakers most often, sometimes Circassians, sometimes Kipchaks. They were converted, trained, renamed. The system was neither uniquely Fatimid nor uniquely Ayyubid, but Egypt made it durable. Cairo’s wealth allowed repetition. Repetition made a culture.

Under the Fatimids, these cavalrymen existed alongside other military households. Their education emphasized horsemanship, archery, lance-work, formation riding, and the etiquette of court. They were drilled to be visible. Fatimid rule was ideological, Ismaʿili Shiʿi, and spectacle mattered. The cavalry were both blade and banner. Loyalty was personal, vertical, transactional. Pay arrived on time or rebellions did.

The Ayyubids inherited the system while quietly sharpening it. Saladin’s Sunni restoration did not dismantle the Mamluk cavalry. It reorganized them. New barracks. Tighter discipline. More brutal expectations. The cavalry’s psychology shifted from ornament to instrument. They became a closed fraternity of competence. Initiation was survival. Punishment was public. Advancement was earned in blood, not pedigree. Their loyalty was to the household commander, then the sultan, then the abstraction of jihad as statecraft demanded. Ideology was present, but habit did the heavy lifting.

The myth that they were all ex-slaves bound forever by gratitude is attested in later chronicles and often exaggerated. Manumission followed service. Wealth followed success. Many Mamluks became patrons themselves. The bond was not gratitude. It was professional pride welded to fear.

Tactics: Mobility as a Theology

On the field, the cavalry behaved like a weather system with opinions. They favored movement over mass. Feints were currency. Horse archery softened lines. Lances finished the conversation. They were trained to fight tired, to remount quickly, to read terrain like a ledger. They could advance under missile fire, pull back without panic, and return at an angle that made infantry regret having feet.

Against Crusader heavy cavalry, the Mamluk method avoided frontal stupidity. They bled horses. They targeted cohesion. They made knights chase ghosts until the sun did the killing. Against Bedouin and Turkmen raiders, they punished speed with speed, counter-raiding camps, seizing herds, cutting the supply of tomorrow’s theft. Against urban revolts, they rode narrow streets with a patience learned from siegecraft, using intimidation as an accelerant.

Their defensive capacity was quiet and stubborn. They could hold passes, bridges, wells. Their offensive temperament was predatory. They pressed advantage without ceremony. Their lethality was cumulative. Chroniclers rarely offer per-capita numbers, but the pattern repeats. Engagements ended with broken enemy morale, scattered survivors, and cavalry units still intact enough to fight again next week.

Cruelty followed success like a shadow. Executions were efficient. Prisoners were useful until they weren’t. Later chroniclers dispute the scale of atrocities, and some accounts are embellished, but there is no doubt the cavalry enforced order with terror when ordered to do so. Mercy was tactical, not habitual.

Courts and Knives: Living Inside Power

The cavalry’s internal life was a study in compressed time. Youth was brief. Training was long. Promotion was sudden. Death arrived without announcement. Oaths were real but elastic. The brotherhood policed itself with rumor and steel. Cowardice followed a man. Brilliance attracted rivals. Patronage protected until it didn’t.

Under the Fatimids, factionalism was constant. Under the Ayyubids, it was lethal. The cavalry learned to read court weather the way they read wind. When Saladin died, they watched his sons quarrel and quietly sharpened their autonomy. They served Ayyubid princes across Egypt and Syria, sometimes fighting each other with professional courtesy and personal venom. The state was fragmented. The cavalry was not.

Their legend grew in the gaps. Songs praised their charges. Mosque sermons thanked their vigilance. The people learned a shorthand. When Mamluk cavalry arrived, something was about to end.

The Mongol Test

In 1260, at ʿAyn Jalut, the Mamluk cavalry faced an enemy that had eaten cavalry cultures for breakfast. The Mongols brought discipline, speed, and terror refined across continents. The battle has become a touchstone, sometimes over-romanticized, sometimes flattened into inevitability. What matters is method.

The Mamluks absorbed shock. They used terrain. They concealed reserves. They counter-feinted a master of feints. The victory did not end Mongol power, but it proved something essential. The cavalry system that began as purchased obedience could evolve into sovereign force. The Ayyubid order cracked. The Mamluks stepped through.

This is where myth thickens. Later chroniclers crown the cavalry as saviors of Islam. Modern historians argue about contingency, numbers, and leadership. Both can be true. The cavalry won because they were good at winning that kind of fight, on that kind of ground, with that kind of preparation.

Metamorphosis: From Brotherhood to State

The Mamluk Sultanate followed. What had been muscle became brain. The cavalry did not dissolve. It metastasized into bureaucracy, tax farms, architectural patronage, and ritual violence. The training system remained. The psychology hardened. The brotherhood survived by becoming the country.

This was not a moral victory. It was an administrative one. The same men who rode down enemies now balanced accounts and sponsored madrasas. Their ruthlessness migrated indoors. Succession crises became blood sport. Assassination became punctuation.

The Fatimid and Ayyubid chapters were prologue. The cavalry learned how to exist without a master and how to pretend they still had one. Their cultural afterlife is noisy. They appear in nationalist histories as guardians, in romantic histories as knights of Islam, in sober scholarship as a durable military caste born of slavery and fed by violence.

They were not unique. They were exemplary.

Legacy

They left roads safer and courts deadlier. They broke crusades and broke their own princes. They taught empires that buying boys could buy time, but only training could buy survival. When the banners finally changed and the names on the coins shifted, the cavalry kept riding, because riding was the only honest thing left.

They did not save the world. They reorganized it at spearpoint.

Final Line: Their legacy is a country shaped like a saddle, polished smooth by centuries of men who learned early that loyalty lasts only as long as the horse keeps moving.

Notable Members

Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb (Saladin), 1137–1193

Not a Mamluk by birth, but the architect who made them indispensable. He understood the cavalry as a tool that needed both faith and pay, and he provided both with a steady hand. His campaigns disciplined their appetites and gave them a cause big enough to swallow rivalries. He trusted them without loving them, which kept everyone alive longer. When he died, the cavalry inherited the consequences.

ʿIzz ad-Dīn Aybak, c. 1200–1257

A former Mamluk who clawed his way to the throne after the Ayyubids collapsed. He married power, then learned it bites back. Aybak embodied the system’s promise and its cost. His reign was brief, violent, and instructive. He proved the cavalry could rule, and that ruling invited knives.

Saif ad-Dīn Qutuz, d. 1260

The sultan who carried the cavalry into ʿAyn Jalut and lived just long enough to win. His leadership in the Mongol crisis was decisive and unsentimental. He was murdered on the road home by men who wanted the crown more than the memory. Qutuz is remembered for a victory and a warning. Win first. Watch your back immediately.

Rukn ad-Dīn Baybars, c. 1223–1277

A Mamluk’s Mamluk. Scarred, brilliant, merciless. Baybars turned battlefield competence into statecraft and made terror an administrative tool. He fortified coasts, crushed enemies, and sponsored mosques with the same hand. Chroniclers alternately praise and recoil. He understood the cavalry as an institution that must never rest.

Resources

al-Maqrīzī, al-Sulūk li-Maʿrifat Duwal al-Mulūk.

Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh.

David Ayalon, Studies on the Mamluks of Egypt.

Peter Thorau, The Lion of Egypt: Sultan Baybars I and the Near East in the Thirteenth Century.

Amalia Levanoni, A Turning Point in Mamluk History: The Third Reign of al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun.

Anonymous Stablehand, Horse Sweat as Political Theory: Notes from the Saddle, Vol. III (Cairo, printed on leather, tragically misplaced).