Kriegsmarine U-boat Crews

(1939–1945)

North Atlantic, Arctic, Mediterranean, Western Approaches

Brotherhood Rank #179

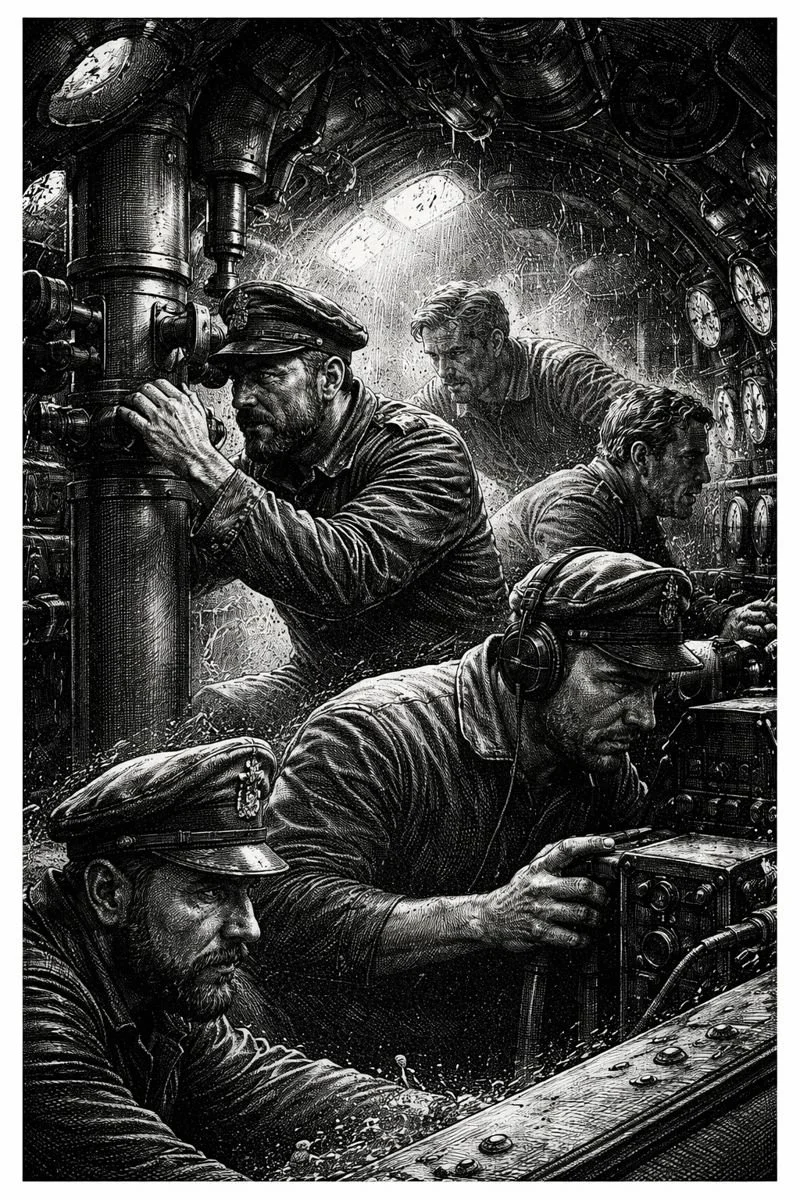

Steel groans before men do. A U-boat under pressure makes its complaints early, popping like knuckles, whining like an animal that knows the sea is trying to fold it in half. Somewhere below the thermocline, depth gauges twitch and sweat beads down bulkheads painted the color of old bones. Diesel fumes mix with unwashed bodies, spoiled bread, and the sweet metallic promise of batteries warming under load. Men count seconds without clocks. They do not pray loudly. They listen. Every sonar ping is a thrown stone, every explosion a hammer searching for the seam.

They live stacked like cargo, boots against faces, faces against torpedoes, torpedoes against faith. They are not cavalry, not infantry, not pilots. They are a pressure-cooked organism sealed inside a steel tube, moving blind through cold water, killing ships they never see die. When they surface, it is brief, furtive, obscene, like a gasp stolen from the enemy’s lungs. Then the hatch slams, and the sea closes its mouth again.

The Kriegsmarine U-boat crews learned early that courage was useless without silence and discipline was useless without luck. They learned the smell of fear in men they trusted with their lives. They learned to read the ocean’s mood the way farmers read skies. They learned that the enemy’s convoys were cities that could drown, and that drowning was contagious. They learned that a torpedo strike was not a duel but an ambush, and that the ambusher still bled when the dogs arrived.

They also learned that survival was arithmetic. Battery hours minus depth minus noise minus air. The sums were unforgiving. Mistakes echoed. Panic killed faster than water. And through it all ran the unspoken truth that every patrol ended the same way: return, be sunk, or be hunted until the steel learned its breaking point. The ocean kept its books meticulously.

Origins in Humiliation and Steel

German submariners did not emerge from nothing. They rose from the wreckage of defeat. The First World War had ended with Germany forbidden a submarine fleet, its U-boat tradition formally strangled by treaty but never buried. Engineers kept sketches. Officers kept memories. Doctrine smoldered in notebooks and mess halls. When rearmament came, it came fast and crooked, a clandestine sprint to rebuild what had once starved Britain and terrified the Atlantic.

Karl Dönitz, himself a veteran submariner of the earlier war, understood that submarines were not ships but weapons systems with souls attached. He preached pack hunting, centralized command, and relentless pressure on merchant shipping. The U-boat arm was sold as elite, modern, decisive. Young men volunteered for the danger because danger promised purpose. The boats were cramped, the pay modest, the odds bleak, but the identity was intoxicating. They were the silent service before silence was fashionable.

Training was brutal but selective. Crews learned to operate blind, to trust instruments and each other over instincts screaming to surface. Mistakes were punished with humiliation, repetition, or expulsion. There was no room for heroes who could not follow orders. There was no room for cowards who could not endure weeks without sunlight. The U-boat was not a democracy. It was a hierarchy welded together by necessity.

The Psychology of the Steel Coffin

U-boat crews functioned as closed ecosystems. Ten, twenty, fifty men living in a space smaller than a city bus for months at a time developed habits that bordered on ritual. Jokes grew darker as air grew thinner. Superstitions hardened. Some boats carried mascots. Others banned whistling, singing, or shaving before contact. Commanders learned the art of controlled terror: enough fear to keep men sharp, not enough to make them brittle.

Sleep came in fragments. Men learned to rest amid noise, vibration, and the constant awareness that a single cracked valve could end everything. Hygiene became theoretical. Food spoiled early. Bread grew mold that was scraped off and eaten anyway. Fresh water was rationed like contraband. When a boat stayed submerged too long, the air turned sour, heavy with carbon dioxide and regret.

The psychological strain did not make them saints. It made them efficient. Empathy dulled. Targets became tonnage. Explosions became confirmation. Survivors in the water were problems, not people. This was not unique to Germans, but the U-boat war made it intimate. Men listened through hydrophones as ships broke apart, as bulkheads collapsed, as cargo shifted and drowned crews screamed into static. Silence afterward felt like success.

Kill Patterns and Cold Arithmetic

Early in the war, the U-boats feasted. Allied convoy systems were immature, air cover sparse, radar unreliable. Lone ships burned across the Atlantic like candles. Crews learned to stalk at night on the surface, using darkness and low silhouettes to slip inside escorts and strike from absurdly close range. The “happy time” was not happy so much as efficient. Sinkings climbed. Decorations followed. Propaganda bloomed.

Tactics emphasized patience and coordination. A single boat might shadow a convoy for days, radioing position while conserving torpedoes. Wolfpacks assembled like a slow tide, converging under centralized command. Attacks came in waves, confusing escorts, overwhelming defenses. When it worked, it was devastating. When it failed, the boats paid in steel and blood.

The arithmetic shifted by 1942. Allied technology accelerated. Radar improved. Huff-Duff triangulated radio transmissions. Aircraft closed the mid-Atlantic gap. Depth charges multiplied and learned to think. Hedgehogs and Squids punched downward with murderous precision. What had been a hunt became a siege, and the hunted were now hunted constantly.

Loss rates soared. Crews went to sea knowing the odds had turned savage. Replacement boats were rushed. Training shortened. Veterans died faster than they could be replaced. The brotherhood absorbed new men who learned terror in real time, under fire, with no rehearsal.

Discipline, Command, and the Edge of Obedience

Commanders carried godlike authority inside their boats. Their word governed depth, speed, attack, and silence. Good commanders cultivated trust and restraint. Bad ones ruled by fear and burned through crews like fuel. Mutiny was rare but not unheard of. More common was quiet dissent: a delayed response, a missed bearing, a hesitation that could be blamed on instruments.

Punishment at sea was limited. There was nowhere to put prisoners. Discipline relied on reputation and memory. Men remembered who panicked, who froze, who cut corners. Survival depended on collective competence, and incompetence was not forgiven easily.

The ideology of the regime pressed down from above, but inside the boat it thinned. Men cared about each other more than slogans. Loyalty was local. The Führer was distant. The captain was everything. This did not absolve them of crimes, but it explains the shape of their obedience.

Atrocity and Indifference

U-boat warfare was ruthless by design. Merchant sailors were legitimate targets under German doctrine, and early adherence to prize rules evaporated under pressure. Ships were sunk without warning. Lifeboats were ignored. In some documented cases, crews fired on survivors or denied assistance deliberately. These acts were not universal, but they were not anomalies either. The ocean learned to expect no mercy.

The Laconia incident of 1942, where U-boats attempted a rescue and were attacked from the air, hardened attitudes further. Orders followed discouraging rescue attempts. Compassion became a liability. Men who hesitated endangered their boats. The war at sea stripped morality to its skeleton.

Collapse Under the Waves

By 1943, the U-boat arm was bleeding out. Sinkings plummeted while losses mounted. Boats were destroyed faster than they could be built. The Atlantic became a killing field for submarines. Crews went down with their boats in the dark, unnamed, unrecovered. Some commanders continued to fight with fatalistic resolve. Others knew the war was lost but sailed anyway.

Technological gambits came too late. Snorkels extended submerged endurance but increased vulnerability. New boats promised speed and stealth but arrived in trickles. Training could not compensate for Allied dominance of the air and sea. The brotherhood thinned to ghosts.

When the war ended, surviving submariners carried the pressure home with them. Many were young men who felt ancient. They returned to a defeated nation that had little appetite for their stories. The sea kept most of their comrades. Memory did the rest.

Afterlife and Myth

Postwar narratives split. In some tellings, U-boat crews became apolitical professionals, sailors trapped by duty and circumstance. In others, they remained instruments of a criminal regime. Both contain truth and evasion. The brotherhood was real. So was its service to a murderous state.

Popular culture polished them into archetypes: stoic captains, creaking hulls, noble endurance. Films and memoirs emphasized claustrophobia and courage, often sidestepping the tonnage of drowned civilians. Historians pushed back, rebalancing the scales. The myth still floats. The wrecks do not.

The Kriegsmarine U-boat crews left no monuments on land, only rusting graves beneath shipping lanes, where the sea still presses down and listens.

Notable Members

Karl Dönitz (1891–1980)

A submariner who became an admiral and then briefly a head of state, Dönitz believed in arithmetic more than rhetoric. He built the U-boat arm into a strategic weapon and watched it bleed itself dry against industrial reality. Loyal to the regime until the end, he left behind a doctrine stained by both brilliance and blindness. History remembers him as the architect who refused to stop building when the foundations were already underwater.

Günther Prien (1908–1941)

Commander of U-47, Prien became a national hero after slipping into Scapa Flow and sinking HMS Royal Oak. His success fed the myth of U-boat invincibility at the war’s opening. He vanished with his boat in 1941, swallowed by the Atlantic before the legend could curdle into failure. The sea kept him young and useful to propaganda.

Otto Kretschmer (1912–1998)

Germany’s most successful U-boat ace by tonnage, Kretschmer favored night surface attacks and ruthless efficiency. Captured in 1941 after his boat was crippled, he spent most of the war as a prisoner, surviving while others died. Postwar, he served again in a different navy, carrying the weight of numbers that never quite washed off.

Wolfgang Lüth (1913–1945)

Charismatic, decorated, and deeply enmeshed in the regime’s image-making, Lüth embodied the cultivated face of the U-boat commander. He survived combat only to be shot by a sentry in a tragic postwar accident. His death felt like a footnote written by irony, not fate.

Heinrich Lehmann-Willenbrock (1911–1986)

Commander of U-96, later immortalized in fiction, he became the template for the weary professional. His patrols captured the grind more than the glory, and his survival allowed him to narrate the war from inside the pressure hull. The myth grew around him because he lived long enough to explain it.

Bibliography

Blair, Clay. Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunters, 1939–1942. New York: Random House, 1996.

Blair, Clay. Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunted, 1942–1945. New York: Random House, 1998.

Dönitz, Karl. Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990.

Milner, Marc. The Battle of the Atlantic. Stroud: Tempus, 2003.

Stern, Robert C. U-Boat Commander. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2012.

Kapitänleutnant Otto Schraubenschlüssel. Advanced Submarine Feng Shui and Other Things That Definitely Existed. Berlin: Verlag für Tiefsee-Philosophie, 1947.