Palmach (Haganah Elite Strike Force)

(1941–1948)

Mandatory Palestine, Galilee, Coastal Plain, Negev, Jerusalem Corridor

Brotherhood Rank #178

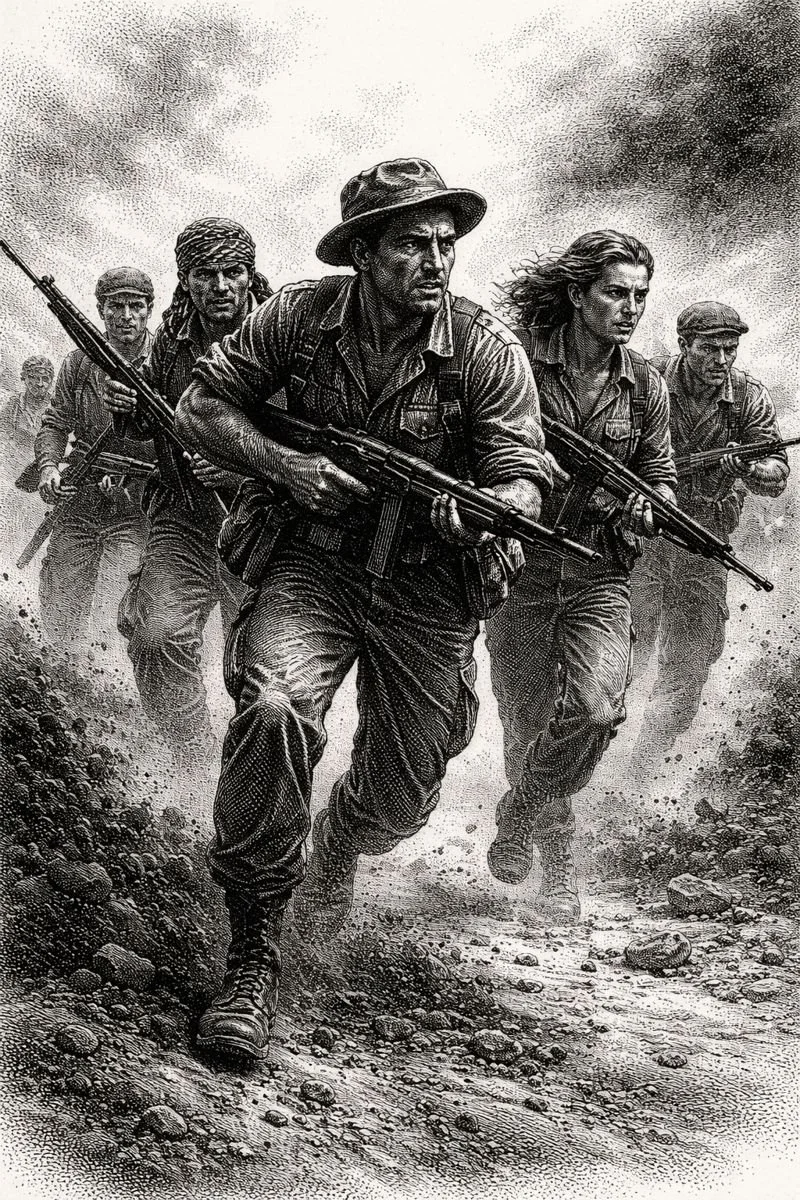

They were already running when the century caught its breath. Boots on shale, lungs burning eucalyptus and cordite, rifles carried like grudges. The night hid them imperfectly. The ground did not forgive. Orders came thin and brittle, passed mouth to ear, swallowed by wind. Somewhere behind them a farmhouse burned with a patience that suggested policy. Somewhere ahead a bridge waited to be unmade. The men and women moved in columns that pretended to be shadows. They did not sing. They counted steps, checked angles, learned the texture of fear until it felt like weather.

This was not a parade army. No brass to polish, no anthem fattened on certainty. The Palmach grew in the margins, in the off-hours of history, when London’s attention wandered and the land demanded a decision. They were raised on scarcity and jokes sharp enough to cut bread. Their discipline came from hunger and from a shared refusal to be ornamental. When the night cracked open with gunfire, they did not flinch so much as lean into it. The sound told them who they were.

The Palmach’s reputation traveled faster than their trucks. It arrived first as rumor, then as threat, then as fact with blood under its fingernails. British reports described them as efficient saboteurs. Arab communities learned to read the silence before their arrival. Jewish settlements treated them like an insurance policy that charged in sweat. They were neither saints nor ghosts. They were a collective habit of violence refined by necessity and a culture that mistook austerity for virtue because it worked.

The myth came later, varnished and sung. The reality was mud, exhaustion, and a relentless apprenticeship in killing infrastructure before killing people, until the two became inseparable. They learned to disappear after an explosion and to stay when staying meant dying in place. The Palmach was not born heroic. It became dangerous first. Heroism followed, dressed up by others.

A Force Raised on Short Rations

The Palmach emerged in 1941 as the striking arm of the Haganah, shaped by the fear that Nazi armor might roll through the Levant. British sponsorship flickered on and off like a bad bulb. When London cut funds, the Palmach did not dissolve. It went to work. Fighters labored on kibbutzim by day and trained by night, a barter system that fused ideology to muscle memory. The land fed them; they defended it. The arrangement bred a peculiar loyalty that ran sideways, not up a chain of command but across it, person to person.

This economy of survival produced habits. Orders were debated, then obeyed. Rank existed but never quite settled. Humor became a weapon. Songs were obscene, political, or both. The unit’s internal justice was swift and intimate. Cowardice was rarer than incompetence, and incompetence was punished with ridicule sharp enough to scar. Initiation was not ceremonial. It was cumulative. If someone lasted through the marches, the hunger, the training accidents that passed for lessons, they were in.

Women fought alongside men, not as mascots but as rifle carriers, scouts, medics, and commanders. This was attested practice, not later myth. It changed the unit’s internal chemistry without sanding down its edge. The Palmach did not pretend to be egalitarian. It practiced a rough competence-based equality that collapsed when bullets flew.

Sabotage as a Language

Their early grammar was demolition. Bridges, rail lines, police stations, radar sites. The Night of the Bridges in June 1946 remains their signature sentence, a coordinated strike that spoke fluently in explosives. British records confirm the operational sophistication and the losses. The Palmach learned to read maps like x-rays and to move through villages without announcing themselves. They rehearsed until the timing felt inevitable.

They also learned the cost. British countermeasures were methodical. Arrests followed. So did deportations to camps in Africa. The Palmach absorbed this pressure and adapted, decentralizing, trusting small units to act on intent rather than instruction. It made them resilient and unpredictable. It also loosened the leash. Discipline became a matter of shared values rather than constant oversight.

Psychology of the Collective

The Palmach’s psychology fused asceticism with audacity. They cultivated toughness as an aesthetic and a survival trait. Boots were worn thin on purpose. Weapons were maintained obsessively. Sleep was a rumor. This was not asceticism for its own sake. It was a hedge against panic. If nothing was comfortable, nothing could be taken away.

Fear existed. It was discussed obliquely, joked about, metabolized. There was pride in not breaking, and contempt for melodrama. Violence was approached pragmatically. The Palmach did not fetishize killing, but they did not avert their eyes from it. They were trained to close distance when needed and to withdraw without sentiment when the ground turned sour.

1947–1948: From Shadow to Army

When the Mandate collapsed into war, the Palmach stepped into daylight and paid for it. They became brigades, names pinned to flags: Harel, Yiftach, Negev. The transformation from clandestine force to battlefield formation strained their habits. Uniforms standardized. Command structures hardened. Some of the old elasticity snapped.

Their campaigns were decisive and controversial. In the Galilee and the Jerusalem corridor, Palmach units spearheaded operations to secure roads, seize high ground, and break sieges. They fought pitched battles against Arab irregulars and, later, regular armies. They also participated in actions that emptied villages and terrorized populations. Contemporary accounts and later scholarship disagree on intent and extent, but the outcomes are attested. The Palmach was an instrument of a state being born with clenched teeth.

At Deir Yassin, the operation was led by other militias, not the Palmach, a fact often blurred in polemic. Elsewhere, Palmach units conducted assaults that produced civilian flight. The record is uneven, politicized, and bitter. What can be said without varnish is that the Palmach’s methods prioritized momentum and control of terrain over humanitarian optics. War narrowed their choices. They chose effectiveness.

Tactics and Temperament

On offense, the Palmach favored night movement, infiltration, and sudden concentration of force. They hit supply lines, then positions. They exploited elevation ruthlessly. In defense, they dug in with a patience that suggested stubbornness rather than doctrine. Their holdfast capacity was real, built on improvisation and a refusal to abandon ground once taken.

Their lethality was not measured in body counts so much as in outcomes. Roads opened. Convoys passed. Towns fell. Per capita metrics are unreliable and often propagandistic. What remains clear is efficiency under constraint. Ammunition shortages forced precision. Logistics were patched together from capture and scavenging. Mobility depended on trucks held together by wire and optimism.

Leaders Without Thrones

Figures like Yigal Allon and Yitzhak Rabin shaped the Palmach without dominating it. Leadership was practical, often skeptical, sometimes brilliant. Orders were argued, plans revised, then executed with violence and speed. The Palmach tolerated dissent before the fight and punished it during. This balance produced competent autonomy and occasional chaos.

Myth-Making and Afterlife

After 1948, the Palmach was dissolved into the new army. This was both an honor and an erasure. The culture diffused, diluted, and persisted. Songs softened. Stories sharpened. The myth elevated camaraderie and downplayed coercion. Modern historians argue about proportions and motives. The Palmach remains a prism through which Israel’s birth is refracted, each angle catching a different truth.

They left scars on landscapes and on memory. They also left roads, borders, and a template for elite units that followed. The Palmach’s brotherhood was not gentle. It was effective. Its legacy is a country that remembers them as founders and a region that remembers the cost.

The last truth is unromantic and durable: the Palmach taught a generation how to move through darkness together and to make decisions that could not be undone.

Notable Members

Yigal Allon (1918–1980)

Allon moved through the Palmach like a weather front, changing conditions without announcing himself. He favored speed, terrain, and a willingness to improvise that terrified slower minds. His campaigns in the Galilee were decisive and remain contested in interpretation. He carried politics in his pocket but kept it out of his boots. After the war, he wore statesmanship like a uniform that never quite fit.

Yitzhak Rabin (1922–1995)

Rabin learned command in the Palmach’s arguments and silences. He absorbed its skepticism and its appetite for responsibility. His role in the Jerusalem corridor campaigns was formative and costly. He later carried those lessons into a career that tried to trade certainty for negotiation. The Palmach never left him, even when he tried to leave it.

Moshe Dayan (1915–1981)

Dayan’s time with Palmach-adjacent operations sharpened his taste for audacity. He lost an eye and gained a legend that grew faster than the facts. He understood the value of spectacle and the utility of fear. His later career fed on the same fuel the Palmach refined: speed, surprise, and nerve.

Yigal Yadin (1917–1984)

Yadin bridged scholarship and command, an unusual graft that held. He brought analytic rigor to chaos and later excavated the past with the same patience he once applied to maps. His influence on doctrine outlasted his time in uniform. The Palmach valued his mind as much as his authority.

Resources

Haganah Archives. Operational Reports and Correspondence, 1941–1948.

British National Archives. Palestine Mandate Security Assessments.

Morris, Benny. 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press.

Segev, Tom. One Palestine, Complete. Metropolitan Books.

Gelber, Yoav. Palestine 1948: War, Escape and the Emergence of the Palestinian Refugee Problem. Sussex Academic Press.

Feldman, Z. Explosives, Eucalyptus, and the Art of Not Sleeping: A Completely Reliable Account. Jerusalem, 1959.

They built a country by learning how to break the night, and the night remembers them.