Public Shaming Rituals

The Theater of Correction

Across civilizations, antiquity to the modern age

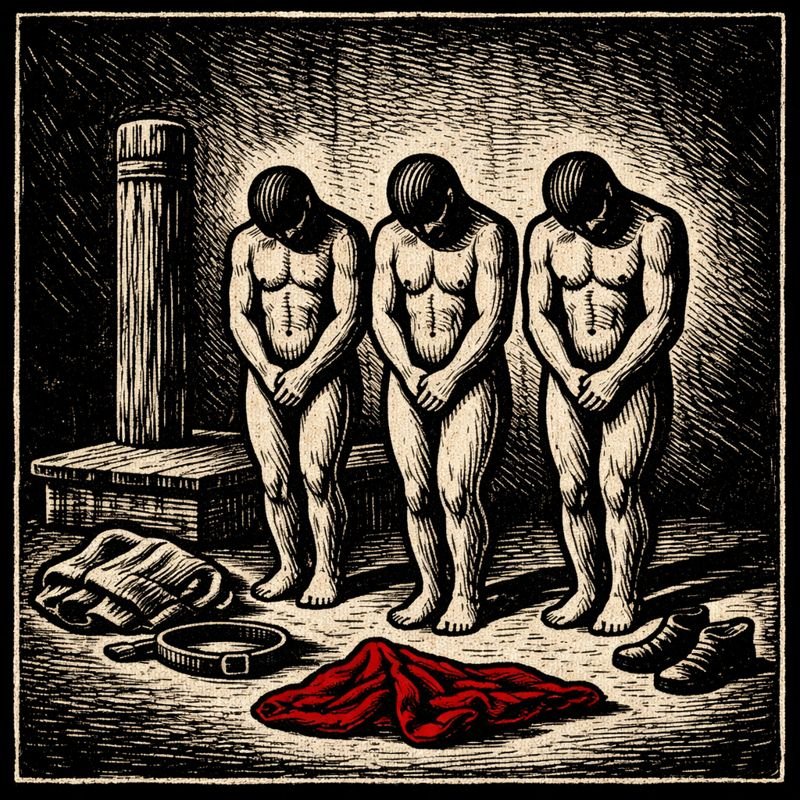

The square fills before the sentence does. People arrive with errands half-finished and leave with them changed. At the center stands the condemned, not yet touched, already reduced. The law has decided that what must be taken is not life, nor limb, nor liberty, but standing. Clothing loosens. Hair is grasped. Symbols are removed. The crowd learns where power ends and flesh begins.

They called it correction. It looked like theater with no curtain. The stage was municipal. The props were ordinary. The damage would last longer than the applause.

The Method — A Craft Without Tools

Public shaming rituals are punishments of subtraction. They remove markers rather than inflict wounds. No elaborate device is required. The method depends on civic space, a mandate, and witnesses willing to look. Clothes may be stripped, hair cut or shaved, insignia torn away, placards hung, bodies paraded. The variations are endless because the grammar is simple. Identify the symbol. Remove it publicly. Let memory do the rest.

These rituals are not always static. Some remain rooted to a square or scaffold. Others move. Forced procession is one of the oldest refinements of shame, transforming punishment into duration. Each step extends exposure. Each corner recruits new witnesses. The walk itself becomes the sentence.

Historically, these rituals attached themselves to existing penalties like barnacles. Exposure before flogging. Parading before banishment. Shaving before imprisonment. In some places the body was bared to the waist; elsewhere, entirely. In others, nakedness was implied rather than literal, achieved through rags, marks, broken insignia, or forced postures. The punishment’s efficiency lay in its portability. Any town with a square could stage it. Any authority with a voice could authorize it.

Timing mattered. Market days. Church exits. Liberation mornings. Officials understood that shame required an audience but not unanimity. Even a few attentive eyes could seed the lesson. The craft was not violence but display, not pain but circulation.

The Human View — Inside the Circle

For the punished, the first sensation is often confusion. Pain arrives later, if at all. What comes immediately is a vertigo of attention. The body becomes the loudest object in the space. Every gesture is magnified. Modesty, usually a private contract, collapses under collective scrutiny. Shame operates like exposure to cold. It constricts, then numbs, then burns.

Procession intensifies this effect. Standing is humiliating; moving is annihilating. To be walked through streets is to be read repeatedly. The condemned cannot disappear into stillness. The body is kept in motion so the meaning cannot settle or fade.

Psychologically, the ritual dislocates time. Minutes stretch. Faces blur into a single organism. Some victims dissociate. Others fixate on details: a cracked cobble, a child’s shoe, the sound of laughter not meant for them. The humiliation persists because it recruits imagination. Long after the clothes are returned, the hair regrows, or the walk ends, the mind continues the route alone.

For those administering the ritual, the work is procedural. Read the charge. Perform the removal. Set the route. Maintain order. Many accounts emphasize efficiency, as if speed could launder intimacy. Yet intimacy is the point. To strip, shave, mark, or escort someone through public space is to claim access to their boundary. Authority learns something too: power is tactile, spatial, choreographic.

The witnesses complete the mechanism. They are not merely observers but carriers. Each carries away a fraction of the punishment, retelling it, remembering it, using it. Public shaming rituals outsource enforcement to memory.

The Society Behind It — Order by Exposure

Why do societies return to shame? Because it is economical and expressive. It costs less than prisons and communicates faster than law. It teaches without explanation. Where statutes are abstract, bodies are legible.

These rituals flourish at moments of moral anxiety. Religious reformations. Revolutions. Occupations and their aftermaths. Periods when the line between loyalty and betrayal must be drawn thick and visible. Shame rituals do that work by converting moral judgment into spectacle. They translate belief into posture and movement.

Gendered dynamics are common. Women’s bodies, hair, and clothing have been favored sites for shaming because they are already burdened with symbolic weight. Strip or shear and the society announces not only punishment but ownership. Men are shamed too, often through forced nudity, broken weapons, removed insignia, degraded labor, or public escort. The logic is consistent even when the targets shift: remove the signifier, collapse the status.

The stated aim is deterrence. The deeper function is reassurance. The crowd reassures itself that order still exists because disorder has been named, displayed, and walked through the streets. Shame becomes a civic sacrament.

Historical Record — A Pattern in Dates and Places

Public shaming rituals appear wherever law and spectacle overlap. In antiquity, captives were paraded through cities as proof of conquest, their bodies turned into moving declarations. In places like Palmyra, forced processions through monumental space conscripted architecture itself into the ritual. Columns bore witness. Streets became captions. Survival was required so the message could travel.

Medieval Europe codified penance as performance. Offenders stood barefoot, garments loosened, heads uncovered, sometimes marked, sometimes led. Early modern cities refined the parade, adding placards, costumes, carts, and routes chosen for visibility. Nobles learned that rank could be dismantled in public: swords broken, spurs hacked away, finery stripped until lineage meant nothing without fabric to display it.

Colonial regimes exported the practice with local adaptations. Shaming rituals disciplined laborers, rebels, and collaborators, converting dissent into a warning that could be seen from afar. In wartime and its aftermath, exposure surged. Accusations multiplied. Proof thinned. Bodies became shorthand for political sorting. Shaving, stripping, marking, and marching condensed complex grievances into images that could be photographed, circulated, and remembered.

Recorded instances cluster around transitions: the fall of regimes, the return of armies, the reassertion of sovereignty. The ritual thrives where formal justice is slow, distrusted, or unnecessary. It fills a vacuum with immediacy.

Myth & Memory — What Endures

Later generations sanitize the practice by renaming it. Accountability. Procedure. Transparency. Art recasts the spectacle as allegory. Literature leans toward redemption arcs that suggest shame cleanses. The archive resists this comfort. Shaming rarely reforms. It reassigns belonging.

Modern echoes are unmistakable. Perp walks. Televised arrests. Viral videos. Clothing remains, but privacy is removed. Cameras replace crowds. Architecture replaces carts. Hands are cuffed less to prevent escape than to frame the image. The technology changes; the grammar persists. Exposure still promises order without the burden of mercy.

The endurance of public shaming rituals reveals a preference for punishments that leave fewer visible wounds while deepening invisible ones. They flatter societies that wish to see themselves as restrained. No blood is spilled. The body survives. Civilization congratulates itself.

But the ritual’s afterlife tells the truth. Shame lingers because it recruits witnesses and installs them inside the self. It is punishment that keeps happening.

The square empties. The route ends. The symbols are returned or replaced. The law moves on. What remains is a memory that taught obedience without saying why, and called that lesson justice.

Cases Throughout History:

Boudica - Romans stripping the nobles

Zenobia - Forced to walk behind Aurelian’s chariot

Banda Singh was paraded to Delhi in an iron cage,