Banda Singh Bahadur

(1670–1716)

Revolutionary Sikh warlord; avenger of Sirhind; red-robed rebel saint.

“Mercy? That’s a luxury for men who haven’t yet seen their own intestines.”

— attributed to Banda Singh Bahadur, allegedly, probably not sober

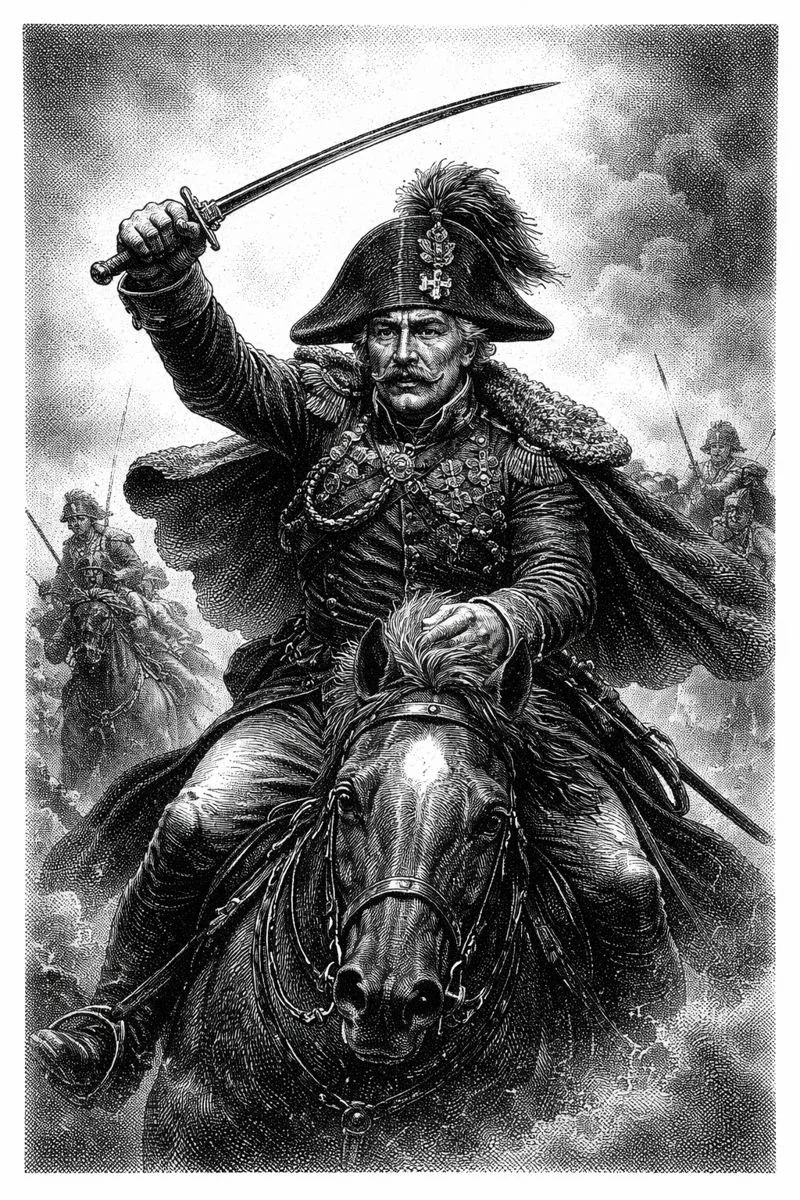

It’s 1710, and the fields of Sirhind are on fire. The smoke tastes of iron and mangoes. Sikh war cries rise over the sound of crumbling Mughal discipline—“Waheguru Ji Ka Khalsa!”—half prayer, half chainsaw. Men in crimson turbans crash through gun smoke like ghosts who forgot to die. At their head rides Banda Singh Bahadur, one hand gripping his sword, the other holding his nerves together by sheer contempt for tyranny. His white horse looks like it’s running through hell with a mortgage to pay.

He doesn’t look like a saint. His eyes are wild, beard ragged, armor mismatched—more apocalypse preacher than general. But in that moment, he’s the wrath of the Khalsa made flesh. Around him, the Mughal lines collapse. Sirhind, the city where the Mughal governor once bricked alive the ten-year-old sons of Guru Gobind Singh, is about to find out what “divine retribution” smells like.

Spoiler: it smells like blood, wet gunpowder, and regret.

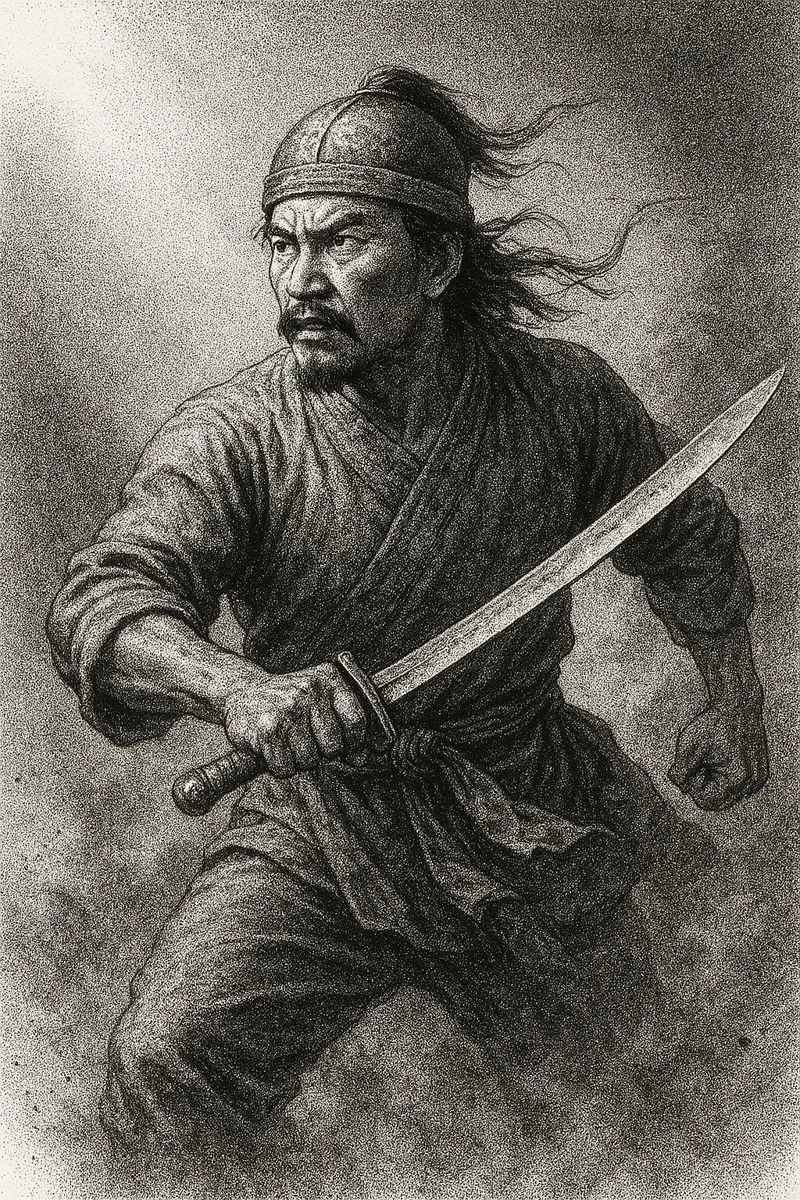

The Saint Who Snapped

Before he became the executioner of tyrants, Banda Singh was a holy man named Lachhman Das, meditating in the forests of Rajouri. A vegetarian ascetic, they say, and soft-spoken—until life kicked him in the teeth. In 1708, he met Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh Guru, who told him about the massacre of the Guru’s family and the rivers of blood left by Mughal persecution. Something in the young ascetic cracked. The monk put down his rosary and picked up a sword.

When he left Nanded, he wasn’t Lachhman Das anymore. The Guru renamed him Banda Singh Bahadur—Banda the Brave Servant—and gave him five arrows and five men. That’s not a metaphor. That’s the full starter pack for a rebellion.

Within two years, Banda’s little warband became a goddamn army.

The Khalsa Unleashed

1710 looked like the Mughal Empire’s hangover year. Emperor Bahadur Shah I was busy playing musical thrones with his brothers, and up north, Punjab was seething. Banda and his Khalsa—an army of farmers, tradesmen, and pissed-off survivors—began burning their way across the plains. They seized Samana, killing the officials who’d executed Sikh saints. Then they hit Sirhind, the Mughal stronghold, where Wazir Khan had murdered the Guru’s sons.

The Khalsa didn’t take prisoners. When the city fell, the people who had laughed at the Guru’s dead children were introduced to a very new theology—one preached with talwars and torches.

Banda Singh didn’t just fight; he rewrote the social order. He issued his own coins and land grants in the name of the Khalsa. For the first time, peasants owned the land they plowed. He told the poor they were sovereign and told the rich they were compost. In a country chained by caste, that was revolutionary—and absolutely unforgivable.

The Mughals called him a heretic. The peasants called him a messiah. His enemies called him “the red-robed demon.” Everyone else called him sir.

The Mad Monk of Punjab

If charisma was gunpowder, Banda Singh was a munitions dump. He fought like a man who’d already seen the end of the world and decided to bring souvenirs. Every battle was a sermon. Every victory, an act of vengeance carved into history.

He didn’t care for imperial etiquette. Where the Mughals issued decrees, Banda sent messages pinned to corpses. He minted coins not in his own name, but in the name of “Guru Nanak-Gobind Singh,” welding faith and rebellion together in silver. He founded a capital at Lohgarh, building a citadel that spat defiance at Delhi itself.

For a brief, electric moment, it worked. The Sikh Confederacy was born in blood and idealism, a flash of equality amid empire.

Then the empire sobered up.

The Fall of the Lion

The Mughal response came slow but heavy—like an elephant learning to dance. By 1715, the imperial army finally cornered Banda Singh in the fortress of Gurdas Nangal. Thousands of Khalsa warriors, starving but unbroken, fought for eight months. When the food ran out, they ate bark. When the water ran out, they drank mud. When the walls fell, they fought with stones and teeth.

Captured, Banda Singh was paraded to Delhi in an iron cage, his followers chained and starving beside him. Contemporary reports describe the procession as a macabre parade: men impaled, beheaded, flayed, their bodies left to rot along the road.

And yet, witnesses said, Banda smiled.

When offered food while his men starved, he refused. When told to convert, he laughed. When forced to watch his son murdered before him, he meditated, motionless. The executioner grew impatient.

They tore his flesh with red-hot pincers. They cut him into pieces. They left the legend intact.

The man died in Delhi in June 1716, but the story didn’t.

Resurrection by Reputation

You can’t kill an idea that’s been baptized in blood. Banda Singh Bahadur became something between Che Guevara and the Archangel Michael in Sikh lore—a symbol of righteous vengeance, revolutionary justice, and pure, unyielding defiance.

His name turned into a banner for those who refused to kneel. The British later painted him as a fanatic; the Sikhs remembered him as a prophet with a sword. Modern India remembers him as both saint and insurgent—a warrior who took the Guru’s gospel and made it scream.

And of course, pop history did what it always does: polished him up. The red robe became “symbolic.” The massacres became “justice.” The rebellion became “a movement.” Banda Singh the man—scarred, furious, tragic—was replaced by Banda Singh the statue.

But the real one? He was the sound of the oppressed finally kicking back, the grim joke whispered by every farmer with a rusted blade: “If the kings won’t protect us, maybe it’s time we protect ourselves.”

Epilogue: Blood and Bureaucracy

The Mughals thought they’d made an example of him. They were right—just not the way they hoped.

After Banda Singh’s death, the Khalsa didn’t vanish. They went underground, reemerging as the Sikh Misls—the warrior brotherhoods that would, a century later, build an empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

It turns out the price of killing a rebel saint is eternal instability. Empires fall. Legends don’t.

And somewhere in the smoke of every revolution since, there’s still a man in a tattered red robe smiling at the executioner.

They flayed his flesh, but he’d already stripped the empire’s soul—turns out you can’t skin an idea.

Warrior Rank #170

Sources (serious & slightly unhinged):

Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Vol. 1: 1469–1839 (Oxford University Press, 1963)

J.S. Grewal, The Sikhs of the Punjab (Cambridge University Press, 1990)

Harbans Singh, Encyclopaedia of Sikhism (Punjabi University, Patiala, 1992–98)

S.S. Gandhi, History of the Sikh Gurus Retold (Atlantic Publishers, 2007)

“Mughal Empire’s HR Department: Banda Singh’s Exit Interview Went Poorly” — Unverified Memoirs of an Anonymous Executioner, 1716, Delhi (definitely fake)

“The Red Saint and the Empire: A Love Story” — Khalsa Today (satirical broadsheet, circa never)

Oral traditions recorded by Bhai Mani Singh, possibly embellished by people who really, really wanted to annoy the Mughals.

U.S. Army officer whose calm, uncompromising leadership at the Battle of Ia Drang defined modern airmobile warfare and the brutal reality of command under fire.

Rank - 139