Abd el-Krim

(1882–1963)

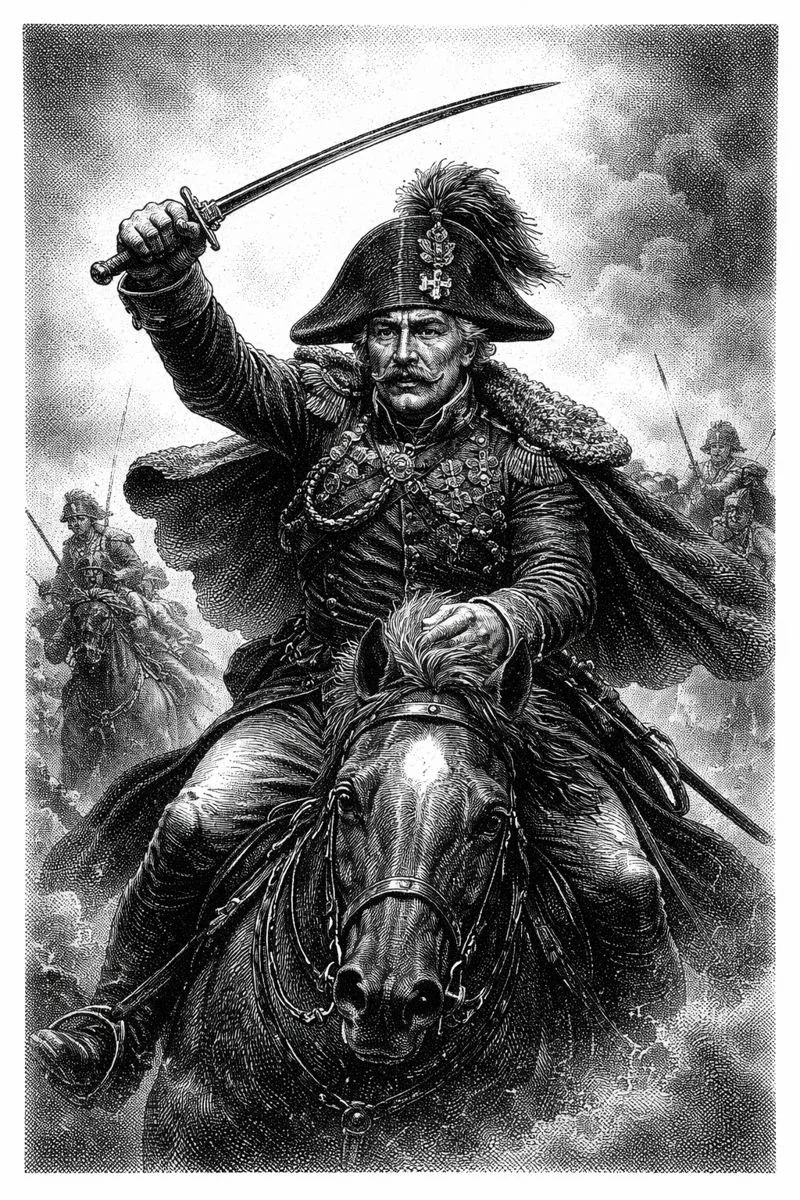

The Mountain Scholar Who Taught Empires to Bleed

“Empires always say they’re bringing civilization. Funny how civilization keeps bleeding out in the dirt.”

— attributed to Abd el-Krim, probably after watching yet another column of Spaniards crumble like wet chalk

Smoke rolls down the ravine like a drunk god’s breath, sour with cordite, dust, and the unmistakable perfume of European panic. You hear it before you see it—Spanish bugles blaring contradictory orders, mules screaming, boots slapping stone, the rapid-fire staccato of rifles that, if we’re honest, are mostly being fired in the wrong direction. And through all that chaos comes a calm voice in the Riffian tongue: “Steady. Let them break themselves.”

Abd el-Krim is sitting his horse like a man who already won the war ten minutes ago and is just waiting for everyone else to notice. The sun is a blade. The canyon is a grave. And Annual—dear, humiliating Annual—is about to become the place where one stubborn Amazigh intellectual with a limp and a library humbles a European empire so hard it considers early retirement.

The Rise of an Unexpected Nightmare

Let’s get this out of the way: Abd el-Krim did not start out as a warlord, desert demon, or the North African John Wick of anti-colonial dreams. He was a judge. A bureaucrat. A newspaper editor. A man who loved reading so much he could’ve been a Berlitz ad. Born around 1882 in Ajdir in Morocco’s Rif mountains, he grew up in a world caught between tribal codes, Islamic scholarship, and European colonial vultures circling overhead.

He studied in Fez. He wrote essays about modernization, governance, and—tragically for Spain—how an occupied people might resist with more than just bravado. He even worked with the Spanish for a time, which, to be fair, is the kind of resume entry that ages like milk in the sun.

Then Spain arrested him for suspected collaboration with the Germans during World War I. This was less because he’d actually done anything and more because colonial powers had a habit of imprisoning educated natives who looked like they could someday spell “revolution.” He escaped—because of course he did—and limped back to the mountains, where he came to a revelation shared by prophets, bandits, and anyone who’s ever quit a soul-sucking job:

If you want something done right, you do it yourself.

The Rif Republic: From Ink to Iron

Most anti-colonial leaders shout slogans. Abd el-Krim built a state.

Not a pretend state or a “we meet on Thursdays in the back of a café” state. No. A functioning, tax-collecting, law-passing, modernizing Rif Republic in the 1920s that made European colonial administrators spit out their over-sugared coffee.

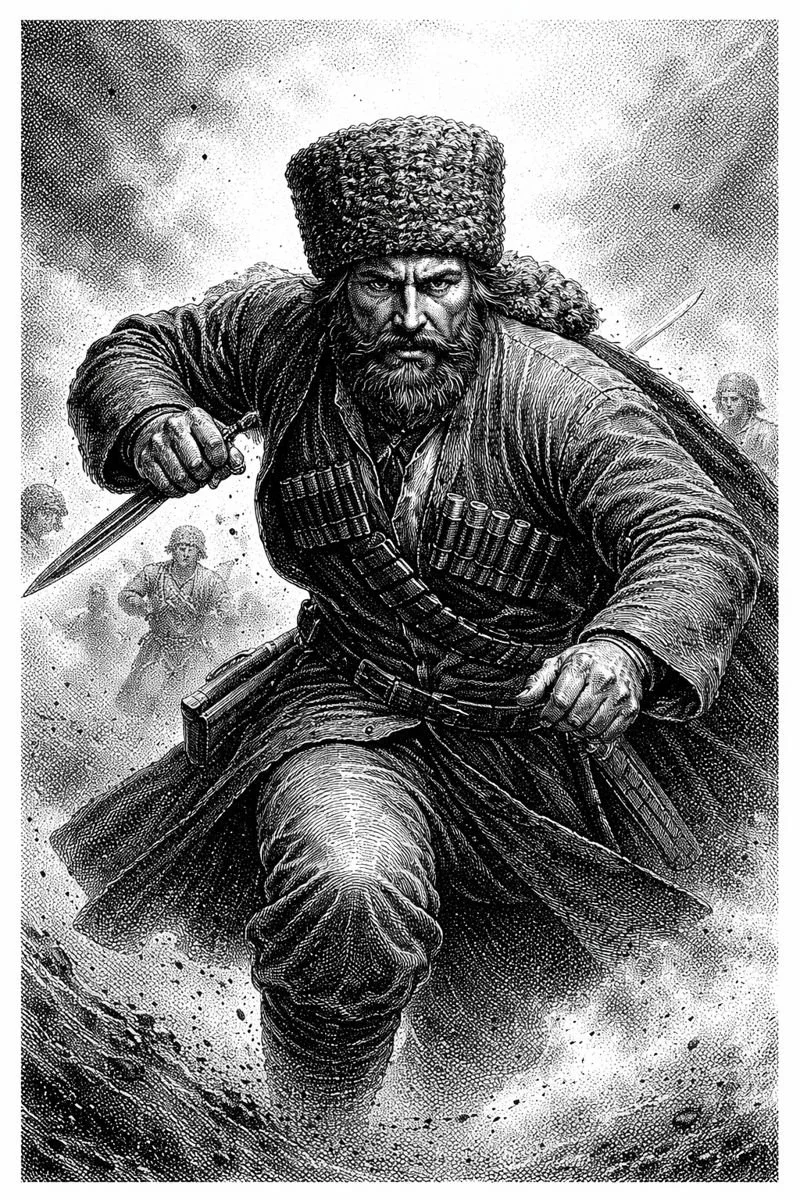

He forged tribal factions into a coherent movement—no small miracle for the notoriously independent Rif clans. He created ministries. Courts. A command structure. He trained fighters with German, Ottoman, and random-mercenary-of-the-week military theory. He built fortifications dug so cleverly into the mountains that, at a distance, they looked like the earth itself growing teeth.

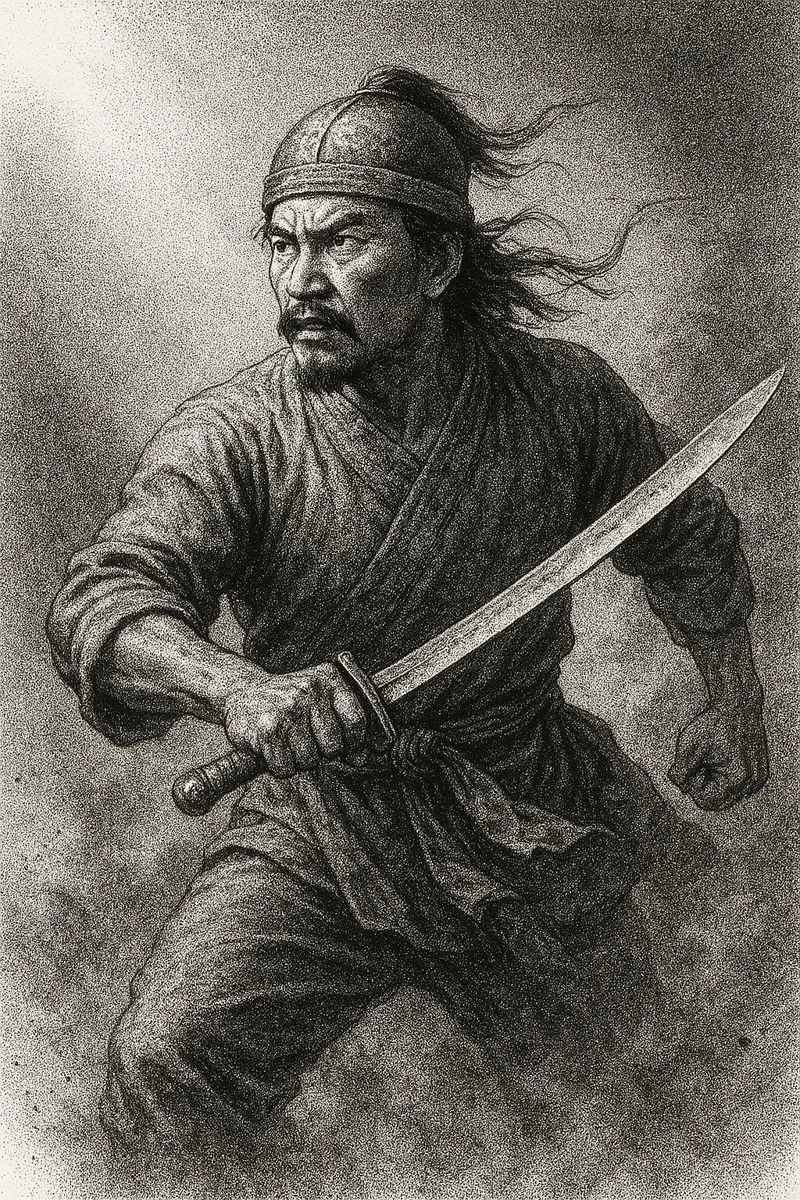

And above all, he preached something the Spanish never believed: that a mountain people armed with rifles, guts, and a terrifying instinct for guerrilla warfare could obliterate a European army.

Which brings us back to Annual.

Annual: The Colonial Oh-Shit Moment of the Century

Picture it: July 1921. The Spanish Army marches confidently into the Rif—because nothing says “good planning” like invading a country you do not understand, across terrain you cannot control, while supply lines sag behind you like wet noodles.

Abd el-Krim watches them come. He waits until they stretch themselves thin, overconfident and under-watered. Then he springs the trap.

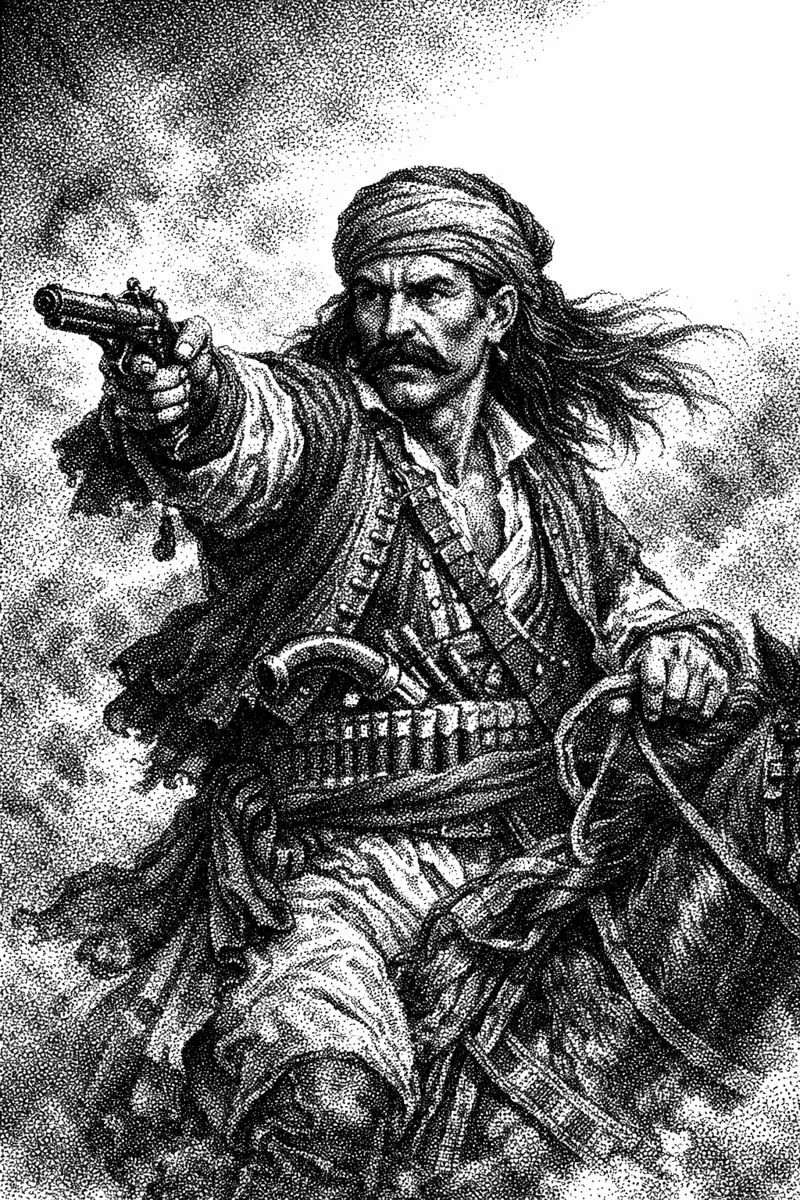

Riffian fighters pour down the cliffs like divine punishment, tight groups of sharpshooters who grew up hitting birds on the wing at 200 yards. They swarm out of ravines that weren’t on Spanish maps. They hit every column, every outpost, every arrogant little forward fort built as though stone walls could stop a people born in rock.

In days—DAYS—the Spanish Army suffers arguably the worst colonial defeat in modern European history. Twenty thousand dead. Artillery abandoned. Commanders fleeing half-dressed. A general allegedly hiding in a bush. Rif fighters collecting so much ammunition from the panicked rout that they joke Spain must’ve shipped them a gift.

Annual isn’t just a defeat. It’s a colonial aneurysm.

And Abd el-Krim? He is suddenly, irrevocably, the nightmare of every European war office from Madrid to Paris. A mountain man who made an empire trip over its own shoelaces and fall down a ravine.

“A Small Problem for Spain” Becomes a Big Problem for France

Spain licks its wounds, cries into its uniforms, and begs France for help. France—always eager to prove it can outdo Spain in both hubris and overreaction—responds by marching into the Rif too.

This is the part in the horror movie where someone says, “We should split up,” and everyone dies.

Abd el-Krim was not impressed by French swagger. In 1925 he attacked their positions, scoring victories that embarrassed them almost as badly as Annual embarrassed Spain. The French military, in response, fell back on its favorite tactic:

“We are losing. Time to commit a war crime.”

Enter chemical weapons.

France dropped more gas bombs on the Rif than a chemist having a nervous breakdown. Mustard gas rolled through valleys, poisoning crops, families, fighters—anything that breathed. It was grim, apocalyptic, and the Europeans pretended for decades it hadn’t happened because nothing says “civilizing mission” quite like blister agents melting your face off.

Even then, Abd el-Krim held out. But two empires at once—even incompetent ones—are hard to beat forever.

The Fall: A Lion Caged by Cowards

By mid-1926, the Rif Republic is bleeding out. Ammunition is low. Food is scarce. Gas attacks scorch the earth. French and Spanish troops—coordinated at last—press in from all sides like the closing jaws of a steel trap.

Abd el-Krim makes a decision almost no warlord ever chooses: he surrenders to save his people.

He walks out not as a beaten man but as a man disgusted by how far his enemies were willing to go to maintain their delusion of superiority. The French exile him to Réunion, a tropical island far from anything and everything he ever fought for.

Does he brood? Of course he broods. But he also studies, writes, and becomes a symbol—proof that a colonized people could stand up, spit in an empire’s eye, and make it blink first.

After years of exile he’s eventually transported to France… where he promptly escapes again. Because Abd el-Krim treats captivity like a temporary inconvenience, the kind one solves by climbing out a window and boarding a boat to Egypt.

He spends the rest of his life in Cairo, advising anti-colonial movements and scaring the hell out of diplomats who want North Africa to stay “manageable.” He becomes a myth—half-fact, half-legend, all stubborn fury.

He dies in 1963, old and undefeated by anything except time.

The Legend: Rebels, Revolutionaries, and Revisionists

Abd el-Krim left more traces in the world’s political bloodstream than most national leaders. Anti-colonial fighters from Ho Chi Minh to the Algerian FLN studied him like scripture. Bin Laden later cited him too—proving that once history makes you a symbol, you don’t get to choose your fans.

Moroccans still argue about who “gets to claim” him—Berbers? Islamists? Nationalists? Historians? The correct answer is: whoever can handle a legacy built on outsmarting two empires and paying for it in blood, exile, and mustard gas.

In Europe, he became a ghost story told by colonial veterans who couldn’t believe they’d been outmaneuvered by a man whose army had more goats than artillery. In Spain, his name still triggers generations-old guilt and the muscle memory of scrambling downhill under rifle fire.

Pop culture mostly ignores him—he’s too serious for Hollywood and too triumphant for European comfort. But in the Rif, he’s the mountain wind: invisible, sharp, and impossible to ignore.

He didn’t win the war. But he won the narrative. And some victories echo longer than any empire survives.

The Closing Shot

History likes to pretend that Abd el-Krim was a “rebellious tribal leader,” but the truth is simpler and sharper:

He was the man who taught Europe that the mountains remember—and they hate being underestimated.

Warrior Rank #171

Sources

David S. Woolman, Rebels in the Rif: Abd el Krim and the Rif Rebellion (serious)

Sebastian Balfour, Deadly Embrace: Morocco and the Road to the Spanish Civil War (serious)

Rom Landau, The People of the Winds (serious)

General Primo de Rivera’s extremely salty dispatches (serious-ish, unintentionally comedic)

The Collected Whining of French Colonial Officers, Vol. 1: “It Wasn’t Our Fault, It Was the Terrain” (tongue-in-cheek)

Mountain Warfare for Idiots: The European Edition (tongue-in-cheek)

U.S. Army officer whose calm, uncompromising leadership at the Battle of Ia Drang defined modern airmobile warfare and the brutal reality of command under fire.

Rank - 139