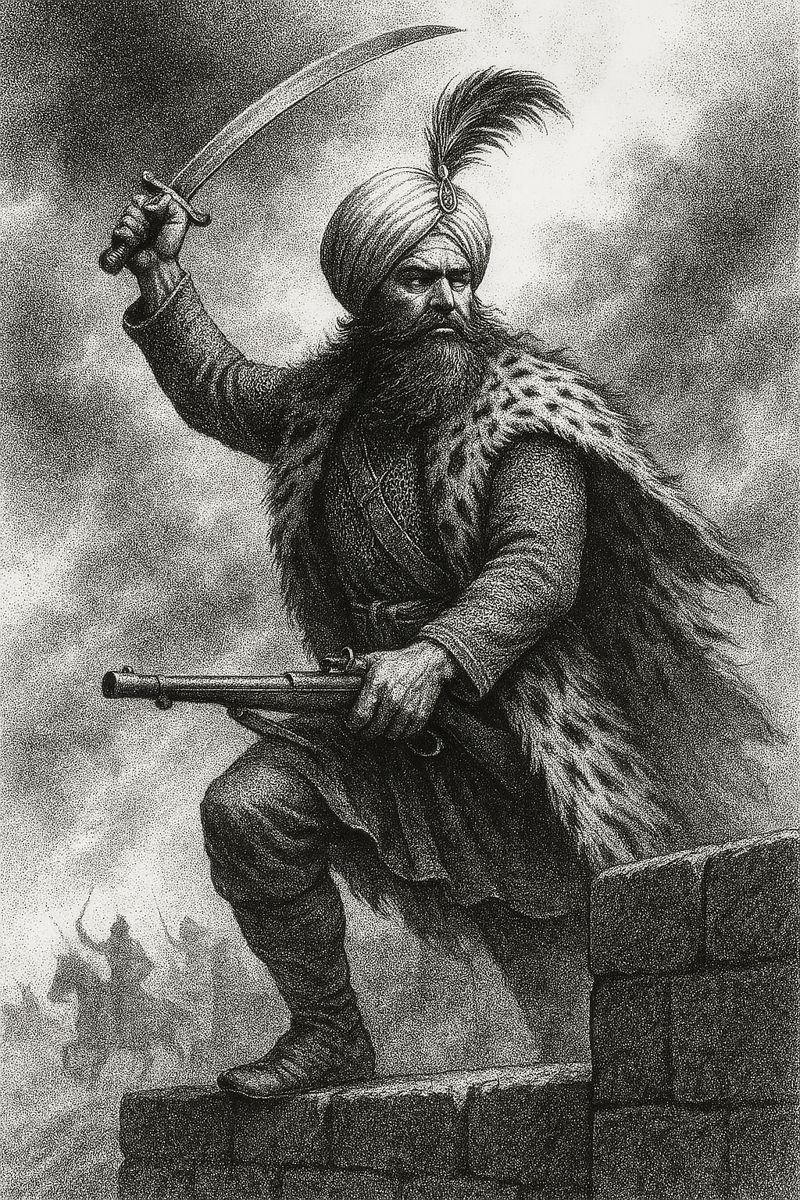

Hari Singh Nalwa

(1791 – 1837 CE)

Sikh lion; frontier conqueror who fixed empires at bay

“God made the man, but Hari Singh made the frontier.”

—Old Afghan proverb, muttered through broken teeth

The first thing the Afghans learned about Hari Singh Nalwa was that you didn’t fight him twice. The second thing they learned was that if you ran, he’d probably chase you into hell just to make sure you stayed there.

It’s 1823, the northwest frontier of the Sikh Empire—Peshawar, the jagged throat of empire, where dust storms taste like old blood and nobody dies clean. The Afghans had been raiding Punjab for centuries, thinking of it as a nice seasonal activity—like harvesting, but with more screaming. And then the Khalsa showed up.

In the middle of that roaring blue tide of steel stood Hari Singh Nalwa, the muscle and moustache of Ranjit Singh’s empire. He wasn’t born royal, but he made royalty kneel. A six-foot Sikh in a world of five-foot corpses, his eyes were the color of molten judgment. Legend says his voice could stop a horse mid-charge. Reality says his sword could cut one in half.

The first time he saw battle, at Kasur, he got his hand nearly hacked off. He didn’t scream. He didn’t retreat. He tied the limb to his side, switched his sword to the other hand, and went right back to killing. The man fought like he owed someone an apology and this was the only language he spoke.

By the time Ranjit Singh unified the Sikh misls into one empire, Hari Singh was his iron right hand—Governor of Kashmir, conqueror of Multan, the empire’s personal nightmare in boots. Every time the Maharaja looked at a map, he saw Nalwa’s fingerprints on another province. “We’ll take Peshawar,” Ranjit said one day. “Fine,” Nalwa replied. “How bloody do you want it?”

The Battle of Jamrud was where his legend turned myth. But before that, there were the amusements: chasing Durrani warlords out of forts, slapping Pathan chiefs into vassalhood, and introducing Afghan skulls to Punjabi architecture. His enemies called him Bagh Nalwa—the Tiger. He wore the title like armor.

There’s a story they still whisper in the passes: once, Nalwa wrestled a live tiger barehanded because it mauled a villager. The beast pounced. Nalwa caught it mid-air. When the dust settled, the tiger was dead and Hari was late for lunch. He had the hide made into a coat and wore it to battle, because subtlety was for the British.

Speaking of the British—those powdered hypocrites were watching closely. The East India Company had learned long ago to fear fanaticism, but the Sikhs weren’t just fanatics—they were professionals. Nalwa’s army didn’t march; it thundered. Drilled, armed, disciplined, and drunk on both faith and adrenaline, the Khalsa were the last serious obstacle between the Company and continental domination. The British took notes. They called Nalwa “the Lion of the Punjab,” which was a polite way of saying “we’d rather not meet him.”

The frontier of India was a godless mess—sand, fever, and men who worshipped nothing but knives. Nalwa’s job was to hold that line. So he built the line himself: a chain of forts from Attock to Jamrud, staring straight into Afghanistan like a dare. And for once in history, the Afghans blinked.

Peshawar fell to the Khalsa in 1834. The Durranis, who had once ridden elephants into Delhi, now fled like thieves. The Sikhs entered the city to the sound of temple bells and musket volleys. Nalwa, true to form, didn’t loot; he administered. Schools, taxes, patrols, law. The Afghans called him a tyrant. The Punjabis called him civilization. Both were right.

But the frontier is never quiet for long. Dost Mohammad Khan, Emir of Afghanistan, wanted his lost jewel back. So he sent an army of tribesmen to remind the Sikhs who used to own whom.

It was early spring, 1837. Hari Singh Nalwa was fifty, which is roughly a thousand in frontier years. His beard had gone white; his temper hadn’t. He was stationed at Jamrud Fort, a half-finished brick claw wedged in the Khyber Pass. A few hundred men under his command. A few thousand enemies coming their way.

You can imagine how that looked.

At dawn, the Afghan host appeared like a sandstorm on fire. Drums, war cries, smoke, banners. Nalwa’s scouts barely made it back alive. Inside the fort, his officers debated retreat. Hari cut them off: “If the Lion retreats, the cubs will follow. Close the gates.”

The battle that followed was textbook frontier apocalypse. The Sikh gunners opened up from the walls; the Afghans swarmed like ants with better curses. Cannon smoke and musket fire turned the fort into a furnace. Nalwa rode along the parapets in his tiger-skin coat, musket in one hand, tulwar in the other, yelling verses from the Japji Sahib between shots.

He was hit by a musket ball early in the fight—gut wound, the kind that makes priests nervous. His men begged him to fall back. He refused. “If they see me die, they’ll lose heart,” he said. So he ordered them to hide his body behind the walls and spread word that the Lion still lived.

He died within the hour. But the rumor worked. The Sikhs fought like lunatics, convinced their general was still watching. The Afghans, demoralized by the endless resistance, eventually withdrew before reinforcements arrived. Hari Singh Nalwa had defended the Khyber Pass even in death.

What followed was the strangest kind of victory. The Khalsa kept the frontier. The Afghans stopped raiding Punjab for good. But the Lion was gone, and with him went the pulse of Ranjit Singh’s empire.

The British later picked apart that empire piece by piece, smiling while they did it. They praised Nalwa in reports, called him “a man of rare courage and genius,” then built their own forts on his bones. Typical.

In Afghanistan, mothers used his name to scare their children into obedience. “So ja, nahi toh Hari Singh aa jayega!”(“Sleep, or Hari Singh will come for you!”)

In Punjab, they sang ballads about the man who stood at the edge of the world and told it to stop moving.

Modern historians sanitize him as “a capable administrator” or “a frontier commander of note.” That’s adorable. The truth is, he was an avatar of organized wrath—a man who built a border out of discipline and willpower, then personally guarded it until his intestines failed.

There’s a grim poetry to his end. The Sikh Empire collapsed within a decade, bled out by politics and British tea-drinkers. But the line Hari Singh Nalwa drew—the one between India and Afghanistan—still stands. The Khyber Pass is still a wound that never heals, and his ghost still patrols it, humming battle hymns through the dust.

The frontier, as they say, remembers.

And if you listen carefully at Jamrud Fort when the wind cuts west, you can still hear a voice muttering in Punjabi: “I told you not to run.”

Warrior Rank # 143

Sources:

The Sikh Empire: Ranjit Singh and His Generals by Jean-Marie Lafont

History of the Sikhs by Khushwant Singh

Afghan Frontier: Feuds, Faith and Fury by Victoria Schofield

Oral folklore of the Punjab & Pashtun regions

“Things the British Took Credit For” — unpublished notes, drunk Punjabi uncle, circa 1974

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125