Queen Amina of Zazzau

(c. 1533 – 1600 CE)

The queen who built walls so her enemies had somewhere to die.

“A woman’s place is in the saddle.”

— attributed to Queen Amina of Zazzau, before conquering someone else’s husband’s kingdom

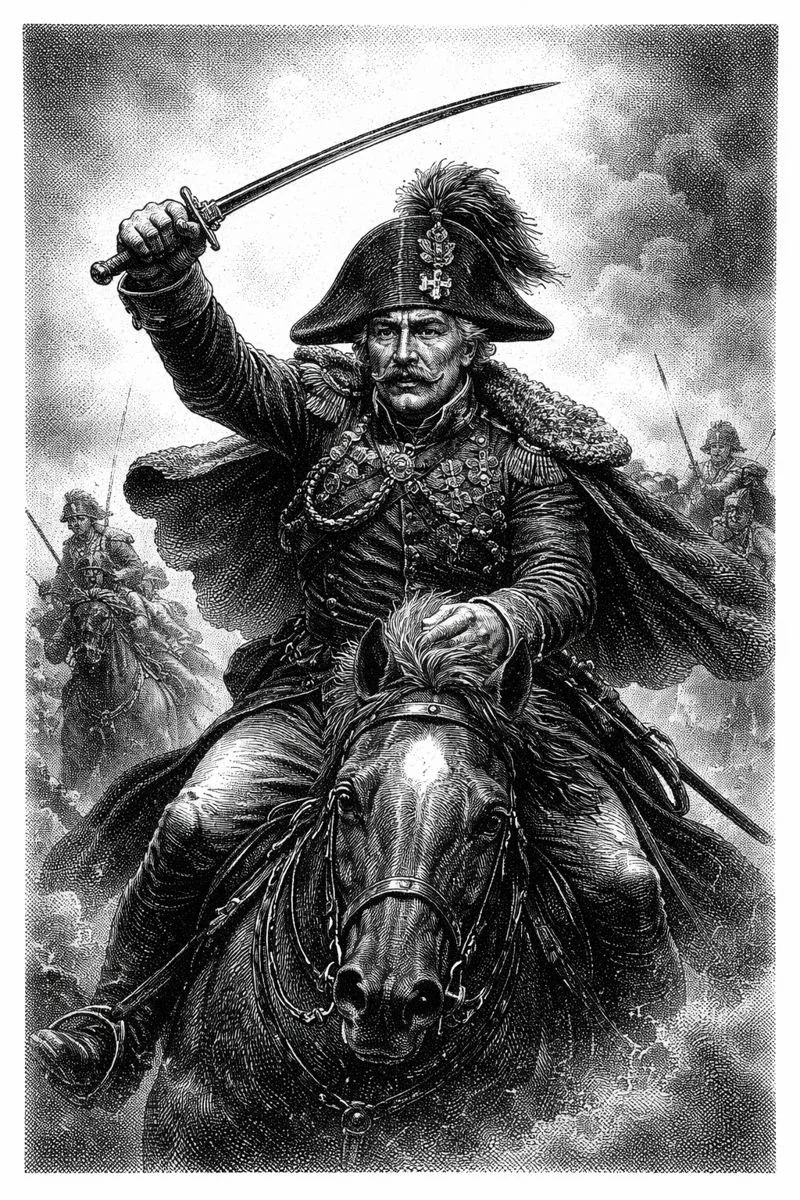

The northern savannah burns gold at sunrise, but this morning it smells like iron and screaming. Riders tear across the dry grass like hornets from a burning nest. Spears flash. The drums sound like thunder having an anxiety attack. And at the center of it all—helmet glinting, jaw set—is a woman who made the Sahara blink first.

Amina, Queen of Zazzau, circa the 16th century—give or take a decade or two, because medieval record-keeping in West Africa had better things to do than timestamp the apocalypse. She’s the Hausa warrior-queen who didn’t just rule her corner of modern-day Nigeria—she fortified it, expanded it, and made her neighbors wonder if maybe diplomacy wasn’t so bad after all.

To say she “broke the mold” is an understatement. Amina ground it into powder and mixed it into the clay of her walls.

The Girl Who Rode Too Hard

She was born around 1533, daughter of Bakwa Turunku, the ruler of Zazzau (modern Zaria). Her mom was already a formidable ruler, so Amina got her first warhorse before her first corset. While other royal daughters were learning courtly etiquette, Amina was out in the training yard spearing straw dummies until they resembled hay-based crime scenes.

When her mother died, her younger brother took the throne (typical), and Amina didn’t pout—she trained. She spent a decade or so commanding the cavalry, proving she could turn a band of horsemen into a mobile buzzsaw. She became so good at killing people for Zazzau that eventually she was allowed to kill people as Zazzau.

By the time she ascended the throne around 1576, everyone knew two things: one, don’t challenge Amina’s authority; two, don’t flirt with her horse—it bites.

The Reign of “No Chill”

Queen Amina didn’t just rule; she expanded. She treated the Hausa city-states like a buffet. Kano, Katsina, Nupe—all fell under her lance. Over thirty years of campaigns, she turned Zazzau from a trade hub into an empire with a body count.

Her armies stretched hundreds of kilometers, her conquests financed by the trans-Saharan trade in salt, gold, and “whatever’s left of your army.” Her genius wasn’t just martial—she understood infrastructure. She ordered walled fortresses built around her territories—massive earthen ramparts called ganuwar Amina, “Amina’s walls.” Some of them still exist today, a reminder that when she said “build a wall,” she actually did.

Legend says she built a fortress every night wherever her army camped. Which, if true, means she ran the most brutal civil engineering internship program in African history.

The Queen and Her Lovers (Spoiler: It Never Ends Well)

Now, because history is written by men with time on their hands, we get some gossip with the bloodshed. Chronicles claim Amina took lovers in every conquered city, but—here’s the fun part—executed them the morning after. Apparently, pillow talk was a capital crime.

Is it true? Probably not. But let’s be honest—it’s a hell of a rumor. Amina, the warrior-queen who stormed fortresses by day and left heartbreak and corpses by dawn, sounds exactly like the sort of bedtime story patriarchy invents when it’s nervous.

Still, the symbolism sticks: she was the one who conquered, not the other way around. Every male-dominated society she rode through had to make peace with that or make excuses. Guess which they chose.

The Moment of Godhood

Somewhere between 1580 and 1600, Amina hit the point of no return—the moment when a mortal stops being a monarch and starts being a myth. Picture her at the head of her cavalry—hundreds of riders draped in dyed leather, the air thick with dust and adrenaline. Her horse rears; she levels her spear at the horizon.

Every tribe, city, and merchant caravan from the Niger to the Benue knows her name by now. Mothers whisper it to their children—half in fear, half in pride. Her soldiers carve it into shields. Traders stamp it into coin routes.

She’s not just a queen; she’s a continental weather pattern.

Death, The Great Plot Twist

The records disagree on how she died—poison, battle, or maybe just exhaustion from carrying West Africa on her back. Oral history leans toward battlefield death, because a woman like that doesn’t die quietly in bed. Some say it happened in Atagara (now near Idah), during yet another campaign.

Picture it: her army victorious but bleeding, the queen’s armor streaked with mud and glory. A spear catches her between ribs—she doesn’t flinch. She orders the attack to continue, blood bubbling through her teeth. When she finally falls, her horse bolts, dragging her half a mile before she hits the dust.

The drums stop. The sky goes silent. The grass remembers.

Her soldiers build one last wall—this time, around her grave.

Myth Maintenance 101

After her death, the legend of Amina metastasized in the best possible way.

The Hausa, the Nupe, even her enemies began claiming some connection to her—bloodline, story, miracle. She became a folk archetype: the warrior-queen, the builder, the avenger. Her story traveled so far that by the time colonial writers stumbled on it centuries later, they didn’t know what to do with her—too violent for a princess, too competent for a footnote.

So they sanitized her. The British chroniclers of the 19th century turned her into an “Amazon,” which is like calling a tiger “a big orange cat with potential.” Missionaries edited her into a moral parable about the dangers of female ambition. Nigerian folklore made her a ghost, appearing on city walls to bless or curse villages depending on their architecture.

And of course, Hollywood ignored her entirely—though, to be fair, no one’s yet figured out how to market Game of Thrones: Hausa Edition without making a mess of it.

Still, her fingerprints remain. Towns across northern Nigeria still trace their old walls to her reign. Oral historians still tell her story at festivals. And every Nigerian girl learning history gets at least one bright, bloody paragraph about Amina—the queen who did everything they said she couldn’t, and then dared to do more.

Legacy: The Wall Stands

Today, Amina of Zazzau lives somewhere between national symbol and mythological cautionary tale. The feminist retellings call her the first woman to lead an African army. The traditionalists say she restored the honor of her ancestors. The skeptics call her an allegory.

Maybe she was all three.

But if you stand on the crumbling edge of an old Hausa wall and squint at the horizon, you can almost hear the drums—hoofbeats rolling like distant thunder, a spear catching the dawn, and a voice shouting across centuries:

“Tell them Amina built this.”

History builds walls to keep women out. Amina built hers to keep the world in.

Sources (more or less sober):

Palmer, H. R. “The Kano Chronicle.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 38 (1908): 58–98.

Sa’ad, A. “Amina: The Warrior Queen of Zazzau.” Kaduna Historical Review 1 (1973): 45–60.

Nigerian National Archives (Kaduna). Oral Traditions Recorded in Northern Nigeria. Field recordings and transcripts, 1950s.

British Colonial Service. “Walls of Amina.” Unpublished field notes, Northern Provinces Administration, 1930s.

Totally Reliable Rumors & Pillow Talk: The Untold Queens of Hausa Land, (unpublished manuscript, possibly imagined).

U.S. Army officer whose calm, uncompromising leadership at the Battle of Ia Drang defined modern airmobile warfare and the brutal reality of command under fire.

Rank - 139