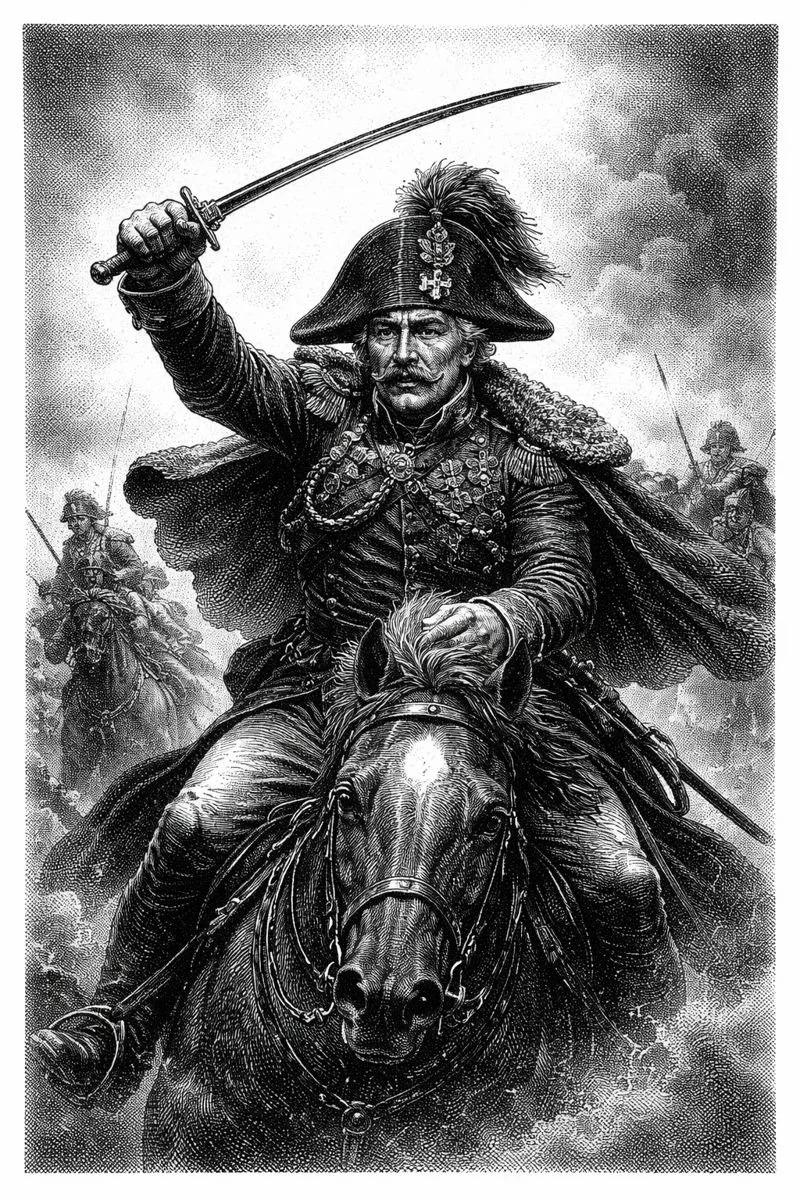

Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher

(1742 - 819 CE)

Relentless Prussian marshal, anti-Napoleon hammer, charged forward, broke empires.

“Forward is the only direction I recognize.”

— attributed to Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, moments before doing something inadvisable

The rain came down sideways at Ligny, turning the Belgian countryside into a brown soup of blood, manure, and misplaced optimism. Cannons coughed iron. Men slipped, screamed, and vanished under hooves. Somewhere in the chaos, a seventy-two-year-old Prussian cavalry general was doing exactly what no one had asked him to do: charging straight at Napoleon Bonaparte like an aging bull with a personal vendetta against geography.

This was Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. To friends, “Papa Blücher.” To enemies, “Marshal Forward.” To his doctors, a recurring headache with legs.

He had no business being there. He was old. He had been trampled by his own cavalry before. He had been captured by the French before. He had spent the better part of his career proving that caution was for people who planned to live past dinner. And yet, here he was again, sword out, mustache bristling, riding directly into the meat grinder of the Grande Armée.

History likes its heroes polished and marble. Blücher was mud, sweat, broken ribs, and rage held together by buttons.

He started nowhere special. Born in 1742 in Rostock, a provincial backwater, Blücher was Prussian in the way bricks are buildings: solid, angry, and allergic to subtlety. He joined the Swedish army first, got captured by the Prussians, and promptly switched sides. Loyalty, for Blücher, was a practical arrangement. He served Frederick the Great and learned the trade of war in an era when discipline meant starvation with extra steps.

He was not clever in the Napoleonic sense. He didn’t sketch elegant maneuvers on maps or wax philosophical about destiny. Blücher believed in momentum. If something was in front of you, you attacked it. If something was behind you, you turned around and attacked that too, just in case.

This approach did not age well during Prussia’s humiliation at Jena-Auerstedt in 1806, where Napoleon crushed the old Prussian army like a brittle relic. Blücher fought anyway, retreating, counterattacking, and refusing to accept the concept of “defeat” even when it arrived in written form. He was eventually surrounded, exhausted, and forced to surrender. The French treated him with wary respect, the way one might regard a wild boar that refuses to die.

Prussia collapsed. The army was gutted. Napoleon restructured Europe like a bored god rearranging furniture.

Blücher waited.

He fumed. He trained. He aged like a piece of iron left in the rain, rusted but dangerous. When Prussia rose again in 1813, fueled by nationalism, vengeance, and an unholy amount of resentment, Blücher was back in command, somehow promoted by sheer force of personality. His real weapon wasn’t strategy; it was stubbornness weaponized into doctrine.

At Leipzig, the “Battle of Nations,” Blücher hurled his troops forward again and again, absorbing casualties like an accountant who refused to acknowledge negative numbers. His army bled. Napoleon’s bled more. When the French finally broke, it was Blücher who wanted to march straight to Paris and kick the door in. Diplomats begged for restraint. Blücher ignored them with professional enthusiasm.

He hated Napoleon with a purity usually reserved for family feuds. This was not abstract rivalry. This was personal. The Corsican had humiliated Prussia, broken its army, and forced its kings to bow. Blücher intended repayment with interest.

Which brings us back to 1815.

Napoleon had escaped exile because history occasionally enjoys slapstick. Europe scrambled. Armies mobilized. Blücher, now well past the age where men are supposed to sit near windows and remember things, took command of the Prussian army one last time.

At Ligny, Napoleon caught him first. The French smashed into the Prussians hard, and Blücher did what he always did: attacked. Late in the day, leading a cavalry charge like it was still 1794, Blücher’s horse was shot out from under him. He went down. Hooves crushed him. French cavalry rode over his body. For a moment, history nearly ended in a puddle.

He survived. Because of course he did.

Pinned under his dead horse, Blücher lay there in the dark, bones broken, lungs screaming, listening to the French pass by. His aides eventually found him, half-dead, soaked, furious. Defeated on paper, he refused the word. Instead of retreating east, as logic suggested, Blücher limped his army north, toward Wellington.

Napoleon assumed the Prussians were finished. This was his last mistake.

Two days later, at Waterloo, the British line was cracking. Wellington was holding on through stubbornness, mud, and divine luck. And then, late in the day, black shapes appeared on the French right. Prussian banners. Blücher had come anyway.

Old, broken, barely able to ride, he forced his army onto the field, hammering Napoleon’s flank while Wellington held the front. It was not elegant. It was not clean. It was decisive. The French army collapsed under the weight of two enemies and one very old man’s refusal to quit.

Napoleon fled. Europe exhaled. Blücher rode into Paris and immediately wanted to blow up the bridge at Jena in revenge. Cooler heads stopped him. Barely.

He died four years later in 1819, not on a battlefield but in bed, which feels like an administrative error. His body was buried. His legend wasn’t done.

Prussia turned him into a symbol: the unstoppable old warrior, the avatar of national revenge, the man who never retreated. Later Germany wrapped him in iron and myth, shaving off the inconvenient bits like recklessness, insubordination, and his alarming habit of charging first and thinking later. His name was given to battleships, streets, and eventually a heavy tank in World War II, because nothing says “historical continuity” like naming a steel monster after a man who treated war as a personal insult.

Pop culture remembers him as the hero of Waterloo. History remembers him as a blunt instrument who happened to be swung at exactly the right moment.

Blücher was not subtle. He was not kind. He was not safe to stand near. He was the last man Napoleon expected and the first one Europe needed.

And when the smoke cleared, the old man finally got what he’d been chasing for decades: not peace, but the satisfaction of seeing his enemy fall before he did.

Warrior Rank # 141

Sources, credible and otherwise

Peter Hofschröer, 1815: The Waterloo Campaign

David Hamilton-Williams, Blücher: The Scourge of Napoleon

Christopher Duffy, The Military Experience in the Age of Reason

Various Prussian officers who survived Blücher and never emotionally recovered

One extremely battered horse, consulted posthumously

Some men retire. Blücher advanced until history tripped over him and broke its nose.

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125