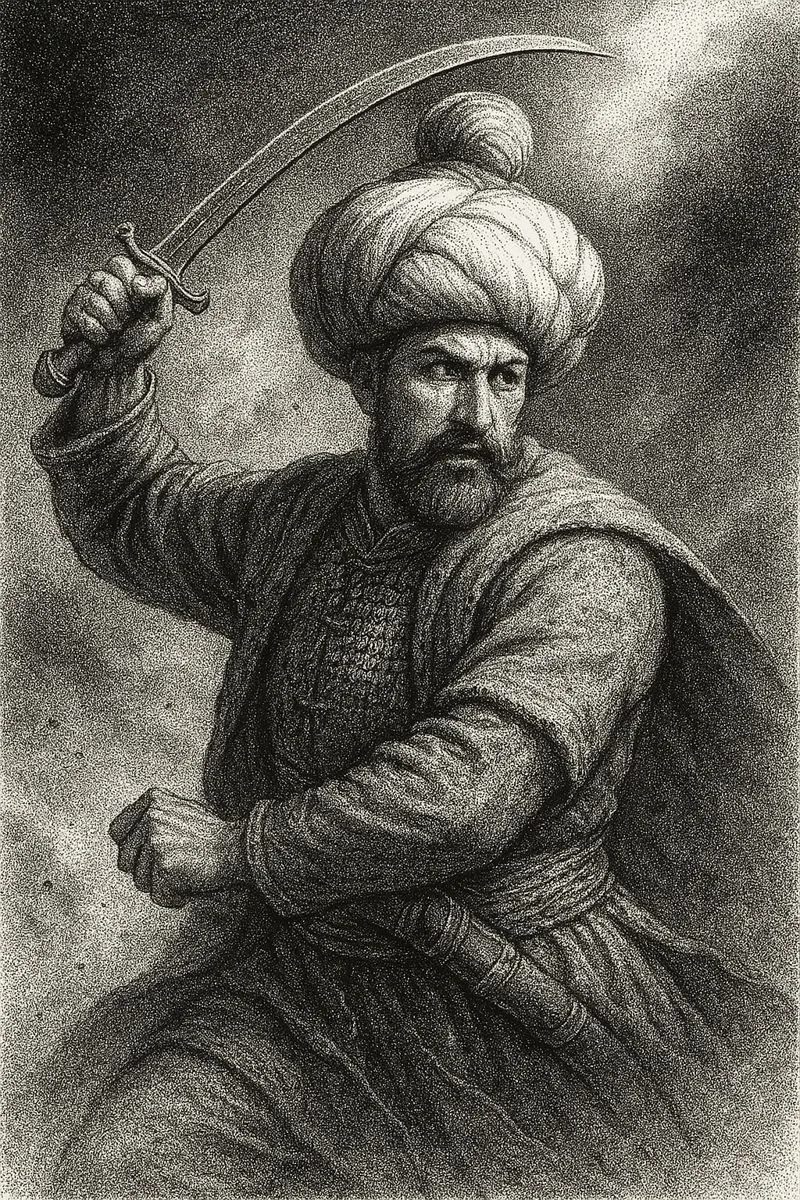

Mehmed II “The Conqueror”

(1432 - 1481 CE)

Ottoman visionary; cannon, faith, and ambition breached Constantinople.

“Either I will conquer Constantinople, or Constantinople will conquer me.” — Mehmed II

The walls of Constantinople had seen a lot of bad ideas. They’d watched Persians, Arabs, Bulgars, Crusaders, and assorted medieval idiots all line up for their turn at disappointment. But on April 6, 1453, they looked out across the plain and saw something new: a teenager with a god complex and a cannon the size of a small cathedral. Mehmed bin Murad, nineteen years old, newly crowned Sultan of the Ottomans, and already looking at the last flickering remnant of Rome the way a wolf looks at a limping deer.

The Byzantines, for their part, were running on fumes and faith. Their emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, had maybe seven thousand defenders, a city full of ghosts, and enough holy relics to choke a mule. The empire that once spanned continents was now basically one big gated community surrounded by enemies. And Mehmed—Mehmed had plans. Big ones.

He called himself Fatih, “The Conqueror,” before he’d even earned it. He studied strategy, languages, and the Quran with equal zeal. He was as comfortable quoting Aristotle as ordering a decapitation. His favorite bedtime stories were about Alexander the Great, and he intended to top them all. Where Alexander stopped, Mehmed planned to plant his banner—and if God objected, well, God would have to learn to negotiate.

The Cannon That Ate Rome

Enter Urban, a Hungarian engineer with more ambition than good sense, who showed up at Mehmed’s court bragging he could build a gun that could knock down the gates of hell. Mehmed paid him well, and soon the Ottoman foundries were sweating molten bronze into something obscene: a bombard 27 feet long, firing stone balls weighing over half a ton. The locals called it Basilica. The Byzantines just called it “oh shit.”

The thing took sixty oxen and two hundred men just to move. It could only fire a few times a day before melting itself into slag, but that didn’t matter. Its roar wasn’t just heard—it was felt. The shockwaves shattered glass miles away, and every blast said the same thing: Rome dies today.

When the bombard opened up on April 12, Constantinople trembled. For six weeks, the city withstood hell. Greek fire met gunpowder. Faith met physics. The Theodosian Walls—those smug, triple-layered, thousand-year-old fortifications—started to crumble.

Inside the city, priests paraded icons through the streets, chanting divine protection. Outside, Mehmed sat in his tent, listening to the distant thud of his monster gun and whispering verses from the Quran. Every night, he rode the lines inspecting his men—Turks, Janissaries, mercenaries, dervishes—all drunk on destiny.

A Teenage God at the Gates of Empire

To call Mehmed confident is like calling the Black Death “a mild inconvenience.” The kid had spent his youth humiliated by his own court, dismissed as too inexperienced, too scholarly, too moody. His father Murad had even come out of retirement once to fix his mess. So when Mehmed took the throne again at nineteen, he was done being anyone’s understudy.

He turned the Ottoman war machine into a religion of its own. He built fortresses along the Bosporus, cutting Constantinople’s throat economically. He created a navy to blockade it from the sea. He marched in with eighty thousand troops and a divine complex you could see from orbit.

On May 29, the final assault began before dawn. The Ottomans came in waves—first the irregulars, then the Anatolian troops, then the elite Janissaries. The air was thick with arrows, screams, and prayer. The Byzantines fought like cornered saints, led by Constantine XI himself, sword in hand, shouting, “The city is fallen, but I live!” before vanishing beneath the crush of bodies.

When the sun rose, the Crescent flew over Hagia Sophia. Mehmed rode through the broken gates in armor spattered with mud and blood, dismounted, and knelt in the great cathedral. “There is no god but God,” he murmured, and in that moment, Islam met Rome—and Rome blinked.

Aftermath: The Conqueror and His Hangover

Constantinople—soon to be Istanbul—was his. Mehmed walked through its burning streets like a man touring his own legend. He spared the survivors, rebuilt the city, reopened the markets, repopulated it with artisans, scholars, and opportunists. He didn’t just conquer; he rebooted civilization.

He renamed the Hagia Sophia a mosque but kept its mosaics. He welcomed Greek scholars to translate their dusty texts into Arabic. He revived trade between East and West. For all his brutality, Mehmed wasn’t a barbarian—he was the apocalypse wearing silk.

He didn’t stop there. Serbia, Bosnia, Albania, Wallachia—they all got their turn. He invaded Italy, besieged Rhodes, toyed with Venice. His empire stretched across three continents. And yet, he wasn’t content. He wanted Rome itself. The man who ended Byzantium still dreamed of sitting in St. Peter’s chair.

But hubris, like artillery, has recoil. Mehmed grew paranoid, executing loyal viziers and family members alike. His Janissaries—once his chosen sons—became his leash. And while he dreamed of another invasion, the great Conqueror suddenly died in 1481, likely poisoned by his own physician. The man who breached Constantinople was felled not by sword or cannon, but by chemistry.

The Ghost of Empires

After his death, Europe painted him as the Antichrist and Islam’s Alexander rolled into one. Christians whispered he drank from golden goblets filled with blood. Muslims remembered him as the Fatih, the sword of faith, chosen by prophecy. The truth—somewhere between genius and genocide—got buried under centuries of propaganda.

His descendants kept his dream alive for another four hundred years. Every Ottoman sultan prayed in his tomb before a campaign. Every European monarch feared his ghost. The cannons he built became museum pieces, but the idea—the will to take what was thought eternal and make it fall—never rusted.

Constantinople, for all its thousand-year arrogance, became Istanbul, a new heart for a new empire. The sound of Mehmed’s cannon faded, but its echo—modernity, nationalism, empire—rolled on.

You can still see his tomb today, tucked away near the Fatih Mosque. Pilgrims whisper prayers there, tourists snap selfies, and somewhere under the marble lies a nineteen-year-old kid who looked at the last light of Rome and said, “Mine.”

They called him “The Conqueror.” But history, in its dry way, might offer a more honest title: The Last Emperor of the Middle Ages and the First Dictator of the Modern.

He’d probably take it as a compliment.

In the end, Constantinople fell not to faith or fate, but to a teenager who treated destiny like a siege engine—and loaded it until it screamed.

Warior Rank #140

Sources:

Babinger, Franz. Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Princeton University Press, 1978.

Nicolle, David. The Fall of Constantinople: The Ottoman Conquest of Byzantium. Osprey Publishing, 2000.

Crowley, Roger. 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West. Hyperion, 2005.

The Chronicle of Kritoboulos of Imbros, trans. Charles Riggs, Princeton University Press, 1954.

“Urban’s Gun: The Monster That Broke Byzantium,” Journal of Medieval Warfare, Vol. 8, 2020.

Possibly the ghost of Alexander the Great, smirking from the afterlife.

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125