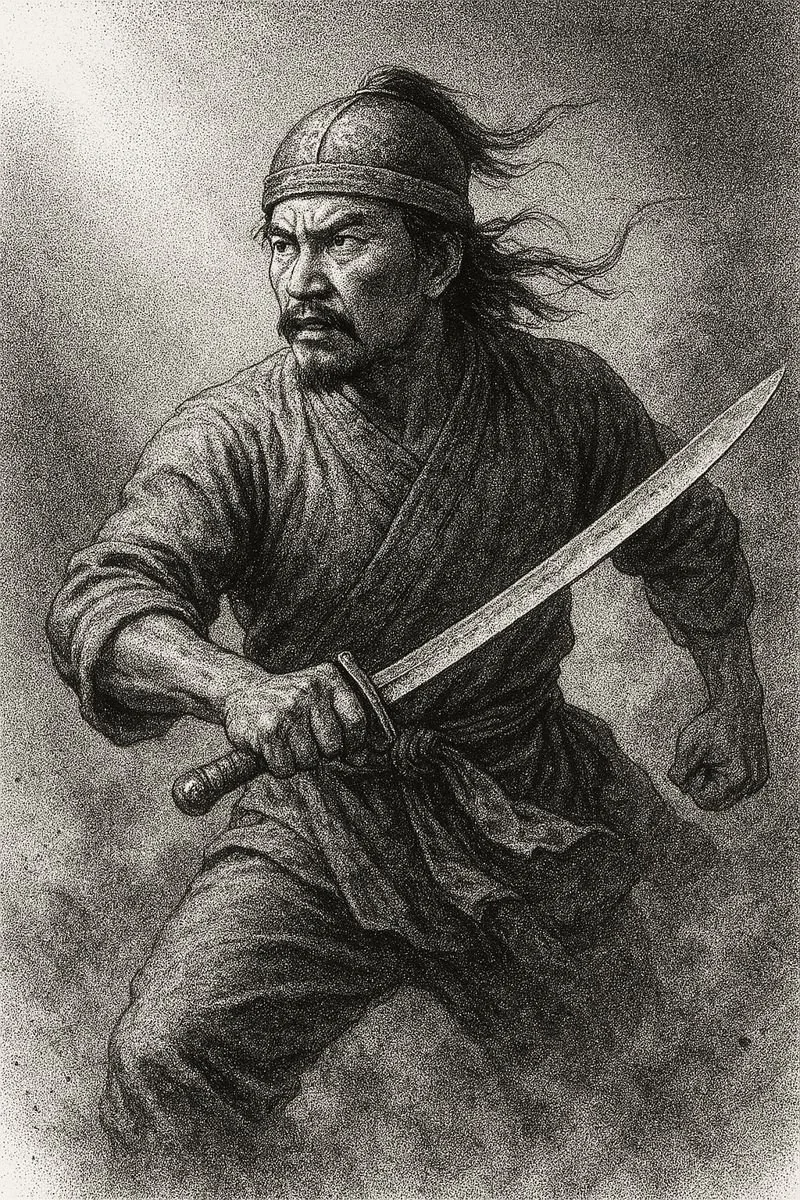

Lê Lợi

(1385 – 1433 CE)

Vietnamese patriot-king; guerrilla brilliance liberated his nation.

“A nation’s freedom is a blade sharpened in the dark.” — attributed to Lê Lợi, maybe, maybe not.

The jungle breathes like a living thing—humid, heavy, and hiding teeth. The rain doesn’t fall so much as hang there, like a waiting ambush. It’s 1427, deep in the hills of Lam Sơn, and the Ming army—China’s finest imperial machine—is being unmade one spear thrust, one poisoned bamboo stake, one whispered rumor at a time. Somewhere under the dripping canopy, a wiry Vietnamese nobleman-turned-guerrilla commander is crawling through the mud with a blade between his teeth and a grudge that could set the world on fire. His name is Lê Lợi, and he’s about to do what no one in his starving, battered homeland thought possible: kick an empire in the teeth until it chokes on its own pride.

Let’s rewind a little.

Vietnam in the early 1400s was a bleeding wound. The Ming dynasty had swept in, toppled the local Trần dynasty, and installed themselves like smug landlords, all while pretending they were “civilizing” the place. They burned libraries, outlawed Vietnamese culture, enslaved laborers, and drained the land of rice and gold. The message was clear: China owned Vietnam, body and soul.

Enter Lê Lợi. A landowner from Thanh Hóa with the face of a farmer and the ambition of a king, he had enough of watching his people bow and die. In 1418, he decided to do something suicidal—raise a rebellion against the most powerful empire in Asia. He called his ragtag army the Lam Sơn uprising, named after his home, and their equipment was mostly sticks, borrowed swords, and pure spite.

In another century, he’d be a freedom fighter. In his own, he was just another lunatic in the jungle.

They say it started with a sword. The legend goes that Lê Lợi found—or was given—a magical blade inscribed with heavenly power, a sword of destiny that shone with justice. The blade supposedly came in two parts: one half pulled from a fisherman’s net, the other discovered in a forest. When joined, they formed the Thuận Thiên, “Will of Heaven.”

In reality? It was probably a decent piece of steel with a catchy backstory. But when you’re trying to get peasants to follow you into hell against armored imperial troops, a little myth goes a long way. “Heaven gave me this sword,” Lê Lợi told them. “Now let’s go return it to the bastards who think they own heaven.”

And damned if it didn’t work.

For nearly a decade, he led a campaign so dirty, so clever, and so unrelenting it makes modern insurgency manuals look like children’s coloring books. He fought from the shadows—ambushes in bamboo thickets, night raids, hit-and-run attacks that left the Ming spinning. When his men starved, they ate bark. When they froze, they burned their own dead for warmth.

The Ming called him a demon. His people called him “the Great Patriot.” Both were right.

At his side was the kind of cast that would make a propaganda poet weep: Nguyễn Trãi, the scholar-strategist who could weaponize words sharper than any sword; Lê Lai, his lieutenant who once disguised himself as Lê Lợi and led a suicide attack so his real commander could escape; and a few thousand dirt-poor, rice-fed badasses who believed they were writing their own epic.

The Ming sent armies—hundreds of thousands strong—down from Yunnan and Guangxi, bristling with crossbows, steel armor, and arrogance. The rebels met them with sharpened bamboo, elephant charges, and psychological warfare that would make Sun Tzu flinch.

By 1426, the tide turned. The Vietnamese had learned to melt away like mist and then hit back like thunder. The Ming general Wang Tong, marching south with 100,000 men, found himself trapped and bleeding in a swamp. Lê Lợi didn’t just beat him—he humiliated him. The Ming troops surrendered en masse.

A year later, at the Battle of Chi Lăng–Xương Giang, the final act came: the Ming relief army was annihilated, its commander tricked into a death march. The empire cracked. Heaven’s Mandate, as the Chinese liked to call it, had apparently decided to take a vacation.

And then came the twist.

In 1428, after ten years of war and starvation, Lê Lợi rode into Thăng Long (modern Hanoi) not as a rebel, but as a king—the founder of the Later Lê dynasty. The Ming, exhausted and humiliated, recognized Vietnam’s independence. The people hailed him as a god-sent savior. The legend of the magic sword came full circle: one day, they said, a giant golden turtle rose from the lake in Hanoi, demanding the return of Heaven’s blade. Lê Lợi dutifully tossed it back into the water. “Heaven’s Will has been done,” he supposedly said. The turtle swam away.

Poetic, sure. Also great PR.

The truth? Lê Lợi didn’t exactly retire to monkhood. His rule was absolute, his paranoia biblical. He purged rivals, executed ministers, and exiled anyone who questioned him—including the same Nguyễn Trãi who’d written his glorious manifestos. The man who liberated a nation became another weary monarch obsessed with conspiracies and ghosts.

Freedom, it turned out, was easier to win in the jungle than to govern in a palace.

When Lê Lợi died in 1433, at 48, he left behind a country scarred but sovereign—and a legend too good to die. His dynasty would rule for nearly 400 years (minus a few brief collapses), and his name became shorthand for Vietnamese resistance itself.

Over the centuries, they polished him into a saintly icon: the patriot-king who rose from mud and myth to cast out the invaders. Statues, schools, and cities bear his name. The lake in Hanoi where the turtle took his sword—Hoàn Kiếm, “Lake of the Returned Sword”—is still there, still green and murky, still full of ghost stories.

But somewhere beneath the marble and myth, there’s the real Lê Lợi: not just the savior of Vietnam, but a man who learned that rebellion is glorious, and ruling is hell.

The thing about revolutions is they never end. The faces change, the flags shift, the speeches recycle. Every generation digs up Lê Lợi’s ghost, sharpens the “Will of Heaven” again, and points it at whoever’s wearing the imperial crown this century.

Maybe that’s the real sword—the idea that some men are born to fight, and others are born to make fighting mean something.

Lê Lợi did both.

He didn’t just win a war. He rewrote what victory meant.

And somewhere in the mist over Hoàn Kiếm Lake, if you squint just right, you can still see a glint of light breaking the surface.

Heaven, apparently, still hasn’t had enough of him.

Warrior Rank #145

Sources (alleged, approximate, and occasionally sane):

Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư (The Complete Annals of Đại Việt), 15th century chronicles.

Nguyễn Trãi, Bình Ngô Đại Cáo (“Proclamation of Victory over the Ming”), 1428 — part poetry, part mic drop.

K.W. Taylor, A History of the Vietnamese (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Oral traditions and turtle enthusiasts around Hoàn Kiếm Lake.

“Heaven’s Will and the Sword That Wouldn’t Stay Dead,” Journal of Southeast Asian Mythology, Vol. 7 (fictional, probably).

Heaven may have lent Lê Lợi its sword—but hell was the one that taught him how to use it.

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125