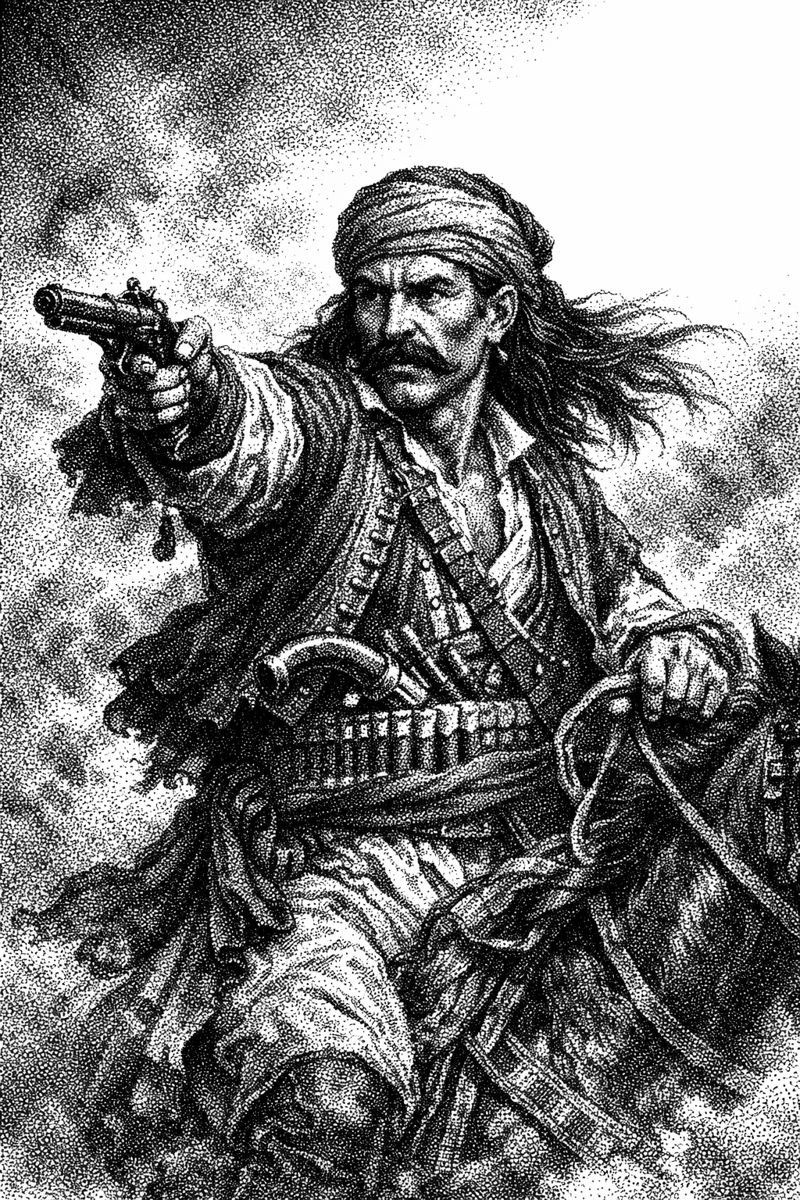

Georgios Karaiskakis

(1780-1827 CE)

Greek revolutionary commander of the War of Independence.

“I was born a bastard and I will die a bastard. The only thing pure about me is my hatred.”

— attributed to Georgios Karaiskakis, probably shouted, definitely earned

The gunshot came from nowhere, which is how all the important ones do.

April 1827. Phaleron. The dust was thick enough to chew, the air buzzing with flies, curses, and optimism’s last death rattle. Greek irregulars crouched behind dirt and bad decisions, facing an Ottoman army that had artillery, discipline, and the confidence of men who had been killing rebels for centuries. Somewhere in this mess stood Georgios Karaiskakis, commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in Central Greece, coughing, swearing, and riding around like a man personally offended by the concept of caution.

He had survived disease, prison, execution orders, betrayal, and his own mouth. He would not survive a random bullet fired by a nervous Greek sentry. History loves irony. It eats heroes with a spoon.

Born Wrong, Raised Worse

Karaiskakis entered the world around 1780 already on the losing side of respectability. His mother was a nun. His father was a klepht. The village solution was to brand him a bastard and move on with their lives. Karaiskakis did not move on. He sharpened it.

He grew up among klephts and armatoloi, those semi-legal Balkan predators who lived by ambush, extortion, and the flexible morality of mountain warfare. The Ottoman Empire tolerated them the way one tolerates wolves: with bribes, threats, and the understanding that sometimes the wolves bite back. Karaiskakis learned early that loyalty was temporary, authority negotiable, and survival a contact sport.

He also learned tuberculosis, which chewed on his lungs for most of his adult life. He hacked blood, rode anyway, and developed the personality of a man who knew he was dying slowly and planned to make it everyone else’s problem.

Rise of a Filthy Genius

When the Greek War of Independence ignited in 1821, it did not begin as a noble revolution with clean flags and stirring speeches. It began as a riot with musket fire. Karaiskakis fit right in.

He was vulgar, brilliant, profane, and strategically gifted in the way only men raised on ambushes can be. He knew terrain like a lover’s scars. He turned peasant bands into mobile nightmares, striking Ottoman columns, vanishing into hills, then reappearing somewhere worse. He insulted priests, generals, and politicians with equal enthusiasm, often in front of witnesses.

He also won. Repeatedly.

That bought forgiveness.

Despite being arrested, accused of treason, imprisoned by his own side, and generally behaving like a rabid genius, Karaiskakis clawed his way upward. By 1826, with the Greek cause fraying and Ottoman forces pushing hard, he was named commander-in-chief in Central Greece. This was not because the politicians liked him. It was because everyone else was dead or failing.

Karaiskakis did not suddenly become respectable. He simply became indispensable.

The Art of Making the Enemy Miserable

Karaiskakis understood something many revolutionary leaders never grasp: battles are optional. Demoralization is not.

He avoided set-piece engagements when possible, preferring harassment, supply disruption, and psychological warfare. Ottoman soldiers feared his name not because he was honorable, but because he was unpredictable. He fought dirty, retreated strategically, and returned at angles that made commanders doubt their maps and their gods.

His camps were chaos. His discipline was personal. His speeches were obscene. His men adored him.

When Athens fell to the Ottomans in 1826, Karaiskakis orchestrated a campaign to harass the besiegers and relieve pressure on the Acropolis. He won key engagements, including a sharp victory at Arachova, where Ottoman troops were annihilated in winter conditions so brutal they seemed biblical. Heads were displayed. Messages were sent.

For a moment, it looked like the Greeks might actually pull this off.

Death by Friendly Fire, Courtesy of Fate

Then came Phaleron.

Foreign advisors, including British officers with polished boots and clean theories, pushed for a conventional assault to relieve Athens. Karaiskakis hated the plan. He said so loudly. He was right. The Ottomans had artillery. The Greeks had courage and vibes.

On April 22, 1827, the day before the planned engagement, Karaiskakis rode forward to observe skirmishing. A shot rang out. Accounts differ. Some say it came from Ottoman lines. Others say it was Greek. The most damning rumor says it was accidental friendly fire. History, again, shrugs.

The bullet struck his lower body. Infection followed. Tuberculosis laughed.

They carried him back to camp. He knew. Everyone knew. The army he held together with profanity and genius was about to lose its spine.

He died the next day, reportedly ordering his men to continue the fight and not waste time mourning him. They mourned anyway. Then they lost the Battle of Phaleron catastrophically. The relief effort failed. Athens remained under Ottoman control.

Karaiskakis did not die in a blaze of glory. He died because someone pulled a trigger at the wrong time. This is how most wars actually work.

From Bastard to Banner

After independence, Greece needed heroes. Preferably clean ones.

Karaiskakis was a problem. He was rude, anti-clerical, insubordinate, and documented as all hell. So the myth machine went to work. The vulgarity was sanded down. The politics simplified. The rebel brigand became a national martyr. Statues rose. Streets were named. Football stadiums borrowed his name and ignored his mouth.

The man who called everyone a bastard became one himself: claimed by the nation, edited for children, embalmed in bronze.

But the real Karaiskakis still leaks through the cracks. In his tactical legacy. In his refusal to bow. In his understanding that freedom is not won by speeches but by men willing to be hated and effective at the same time.

He was not noble. He was necessary.

And that is far more dangerous.

Greece remembers him as a hero, but he lived and died like a curse that just happened to point in the right direction.

Warrior Rank #151

Sources & Further Mischief

David Brewer, The Greek War of Independence

Douglas Dakin, The Greek Struggle for Independence

C.M. Woodhouse, The Greek War of Independence

Greek Army General Staff Historical Service publications

A half-empty flask, a bad map, and the uncomfortable parts of national memory

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125