Haji Murad

(1790-1852)

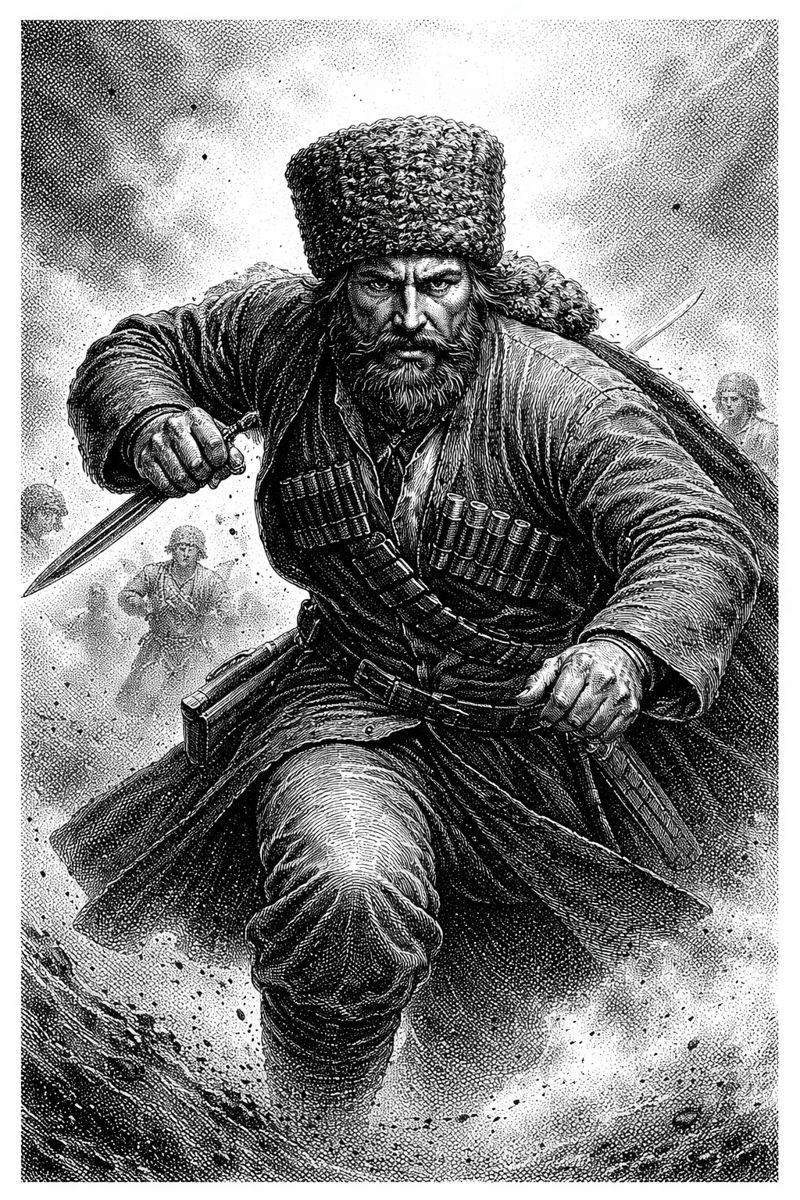

Mountain warlord, master traitor, empire-breaker—killed surrounded, unowned, unforgettable.

“A man can change masters, flags, even gods. He cannot change the mountain watching him bleed.”

— attributed to a Russian officer who survived Haji Murad by accident

The snow had learned his name by then.

Haji Murad burst from the trees like a curse shouted in Arabic, a blur of fur hat, curved dagger, and spite. Muskets cracked. Smoke thickened. A horse screamed the way only horses do when they understand they are about to die for someone else’s ideas. Russian boots churned mud into theology. Somewhere in the chaos, Murad laughed. Not the laugh of joy. The laugh of a man who knows exactly how this ends and intends to make it expensive.

This was 1852, the Caucasus War dragging its diseased body into its fourth decade. The Russian Empire wanted the mountains civilized. The mountains responded by inventing men like Haji Murad.

He had already betrayed everyone worth betraying. He would do it again before sunset.

Born Into Knives and Prayers

Haji Murad was born around 1790 in Avar territory, modern Dagestan, where children learned to walk on cliffs and pray with weapons nearby. The Caucasus did not raise men so much as sharpen them. Blood feuds were inheritance. Loyalty was conditional. Survival was sacred.

Murad was not born a rebel icon. He was born useful. Smart. Ruthless. Charismatic in the way predators are charismatic. He served local khans, then the anti-Russian resistance, then briefly the Russians themselves. If that sounds like opportunism, it was. If it sounds like genius, also yes.

Early on, Murad attached himself to Imam Shamil, the messianic warlord of the Caucasus, a man who combined jihad, guerrilla warfare, and administrative discipline with the enthusiasm of a prophet and the paperwork of a tax collector. Shamil needed killers who could think. Murad needed a ladder made of corpses.

Together they were unstoppable. Shamil supplied ideology. Murad supplied results.

Villages fell. Russian columns vanished into ravines. Officers learned new words for fear. Murad became a legend while still breathing. Songs grew fangs. Mothers used his name to scare children into obedience and inspire them into violence.

Rise of the Necessary Monster

Murad was not Shamil’s equal. He was Shamil’s weapon. And weapons are loved only until they are feared.

Murad’s rise came fast and loud. He led raids with surgical cruelty. He negotiated ransoms with a smile. He understood psychology the way surgeons understand anatomy. He knew when to be merciful and when to make an example that echoed for decades.

The Russians wanted his head. The mountain tribes wanted his favor. Shamil wanted his loyalty.

That last one proved complicated.

Murad grew popular. Too popular. He attracted followers who admired him more than the Imam. In revolutionary movements, that is a death sentence delivered with religious paperwork. Shamil, the prophet-general, began to suspect that Murad’s ambition might someday demand a throne.

So Shamil did what all righteous leaders do when threatened by their own champions. He accused Murad of disloyalty and put Murad’s family under house arrest. Faith became leverage. Hostages became theology.

Murad understood the message immediately.

The Betrayal That Saved Him Briefly

In 1851, Haji Murad defected to the Russians.

Yes. That Haji Murad.

The terror of the Caucasus walked into a Russian fort and asked for protection like a man seeking asylum from his own myth. Russian officers stared at him as if a wolf had requested tea. They gave him a house, guards, and cautious smiles. They called him an asset. He called it temporary.

Murad offered intelligence. Routes. Names. Weaknesses. He promised to help crush Shamil. The Russians, always optimistic about paperwork, believed him.

But Murad’s real goal was smaller and sharper. His family. Shamil still held them. Murad needed Russian help to rescue them. Alliances are easier when desperation does the negotiating.

The Russians hesitated. Bureaucracy crept in. Timetables slipped. Meanwhile, Shamil responded to Murad’s defection with classic moral clarity. He had Murad’s son executed and the rest of the family threatened with the same.

Murad learned this the way warriors usually learn such things. Through whispers that smelled like blood.

Escape Attempt, Mountain Style

In April 1852, Murad decided the Russians were too slow and Shamil was too final. He attempted escape.

This was not a quiet exit. Murad and a handful of followers attacked their guards and fled into the hills. The Russians pursued with dogs, cavalry, and professional resentment. What followed was less a chase than a ritual.

They cornered Murad near the village of Nukha. Surrounded. Outnumbered. Wounded. The mountains watching again.

Murad fought anyway.

He charged cavalry with a dagger. He fired pistols until they were empty. He took wounds the way some men take advice. Poorly, but repeatedly. Finally, a bullet shattered him. Another finished the job. When they cut him down, he was still trying to rise, as if standing were a moral obligation.

They severed his head.

Because of course they did.

The Afterlife of a Head

Murad’s head was sent to Tiflis, then to St. Petersburg, preserved like a specimen. Russian scientists examined it with calipers and theories. Was genius measurable? Was rebellion anatomical? Could treachery be weighed?

The empire that failed to tame the Caucasus contented itself with cataloging its monsters.

Shamil lived on. The war dragged. The mountains remained unimpressed.

Decades later, Leo Tolstoy would write Hadji Murad, turning the blood-soaked warlord into a tragic figure crushed between empires and ideals. Literature sanded off the sharper edges. Murad became noble, doomed, almost gentle. Readers wept. History rolled its eyes.

In Dagestan, Murad remained what he always was. A fighter who chose survival over purity. A traitor to everyone and loyal to himself. A man who understood that flags are temporary but enemies are renewable.

What He Was and Wasn’t

Haji Murad was not a freedom fighter in the modern sense. He was not a nationalist visionary. He was not clean. He was not consistent.

He was effective.

He lived by the only law that mattered in the Caucasus. Win now. Apologize never. Die standing.

Empires hate men like that because they cannot be filed properly. Rebels hate them because they remind everyone that ideology is optional when death is mandatory.

Murad died as he lived. Surrounded, bleeding, unrepentant, inconvenient to all narratives.

Which is exactly why the mountains still remember him.

Warrior Rank # 153

Sources and Further Reading

Leo Tolstoy, Hadji Murad

Moshe Gammer, Muslim Resistance to the Tsar

John F. Baddeley, The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus

Russian Imperial military reports, 1840s–1850s

Local Caucasus oral histories, which disagree with each other loudly

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125