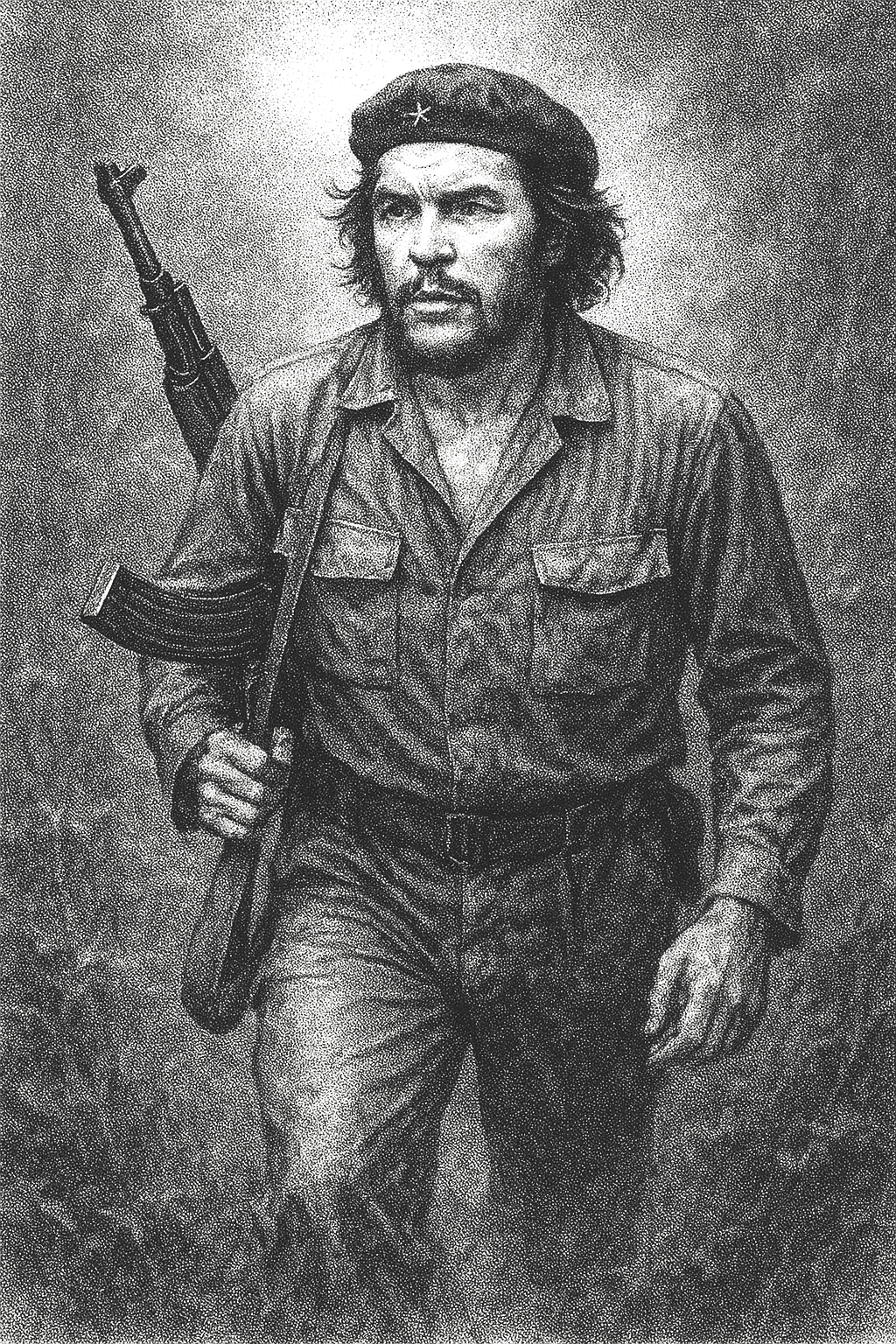

Ernesto “Che” Guevara

(1928 – 1967)

The Doctor Who Prescribed Revolution

“I know you are here to kill me. Shoot, coward — you are only going to kill a man.”

— Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, 1967

Bolivia smelled like wet jungle, diesel, and failure. Che Guevara — doctor, guerrilla, brand icon, and poster child of every freshman dorm — was coughing blood into his beard and still lecturing his men about revolutionary theory like they weren’t starving to death. His boots were ruined, his asthma was back, and the Cuban dream had gone sour somewhere between the ideal and the machete. Once he’d thought the revolution would spread like wildfire; now it was just smoke and mosquitoes.

In the green hell outside La Higuera, the man who’d helped bring down a dictator and danced with history was now being hunted by conscripts with American radios and itchy fingers. It was 1967, and the world’s most photogenic rebel had finally met a country too poor to romanticize him and too mean to care.

The Bolivian army didn’t fear him. They were annoyed by him. To them, Che was a bearded Argentinian tourist in bad health, wandering their hills quoting Marx. To the CIA, he was a PR nightmare who refused to die when it was convenient. To his own men, he was either a prophet or a lunatic — the line between the two measured only by how empty your stomach was that day.

The Doctor Who Prescribed Revolution

Born in Rosario, Argentina, in 1928, Ernesto Guevara was a middle-class kid with asthma and an appetite for both books and bullshit. He read Freud, Marx, and the poetry of Neruda; he rode motorcycles through South America and saw the continent’s sickness — poverty, exploitation, inequality — up close. It disgusted him. He diagnosed capitalism as the disease and armed revolution as the cure. He was, in short, the world’s first militant gap-year student.

After medical school, he drifted north like a politically unstable tumbleweed and found the only man capable of making him look sane: Fidel Castro. The bearded messiah of the Sierra Maestra needed a medic who could shoot, and Che needed a war to validate his ideals. Together they built an army of peasants, dreamers, and sociopaths who overthrew Fulgencio Batista — a dictator so corrupt even the mob thought he was tacky.

When Havana fell in 1959, Che traded his rifle for a minister’s desk. He became the Revolution’s poster boy: finance minister, commander, executioner, philosopher. He ran the firing squads at La Cabaña prison with a bureaucrat’s efficiency and a poet’s justification. “To send men to the firing squad,” he said, “judicial proof is unnecessary.” It wasn’t cruelty; it was cleansing. The revolution needed pure lungs, not debates.

He oversaw land reform, literacy campaigns, and the nationalization of industry — all while Cuba’s economy collapsed faster than his own patience for dissent. To the world, he was the revolutionary idealist in fatigues; to his colleagues, he was the guy who scolded you for enjoying imported wine. Che preached the virtue of asceticism while chain-smoking and wearing a Rolex.

By the early 1960s, he was restless again. Cuba was now a bureaucratic state with Russian babysitters, and Che had never been good at staying in one place. He wanted to export the revolution — to turn the world into one big guerrilla seminar. The problem was that most of the world didn’t want his particular brand of liberation.

Congo: Jungle of Delusions

In 1965, he slipped out of Cuba under a false name, left his family, and flew to Africa to help lead a rebellion in the Congo. His plan: unite the anti-colonial movements under Marxist banners, strike at imperialism’s heart, and probably get malaria.

What he found was chaos. His African comrades didn’t share his discipline or ideology. Some couldn’t read; others couldn’t shoot straight. The local commander believed in magic bullets more than Marxist dialectics. Che, ever the micromanaging messiah, tried to impose structure on a war that barely qualified as one. His asthma flared. His men deserted. His beard collected more rain than victories.

He fled after seven months, half-dead and humiliated. The Congo adventure convinced him of one truth: you can’t spark a revolution in a place that doesn’t want to burn. But that lesson didn’t stick.

Bolivia: The Last Stand

Bolivia was supposed to be different — the perfect tinderbox. Poor, oppressed, mountainous. He would ignite Latin America from its miserable center like a Marxist Prometheus. What he didn’t account for was reality: no peasant uprising, no local support, no food, and no sense of direction. His “Army of National Liberation” numbered fewer men than a soccer team and included Cubans, Bolivians, and one German Marxist whose name nobody could pronounce.

By 1967, the Bolivian army had help from the CIA, who trained and equipped a special unit just to catch him. Radio intercepts gave away his movements. His comrades were captured, tortured, and turned into informants. The revolution died not with a bang but with a whimper and a wheeze.

In October, Che’s ragged band was surrounded near the village of La Higuera. After a brief firefight, his gun jammed, and he surrendered. The Bolivians couldn’t believe it. The legendary guerrilla, the global icon, the guy on the posters — captured alive, coughing, clutching a broken rifle. They marched him into a schoolhouse, tied his hands, and radioed for orders.

The CIA wanted him alive for interrogation. The Bolivians wanted him dead for morale. Eventually, both agreed: a corpse made a better message.

The next morning, Sergeant Mario Terán was chosen to do the honors. Che faced him calmly. “I know you are here to kill me,” he said. “Shoot, coward — you are only going to kill a man.”

Terán fired point-blank into his chest and arms, avoiding the head so the journalists could have their martyr. Che died slowly, bleeding on the floor of a rural schoolroom, eyes open, one last revolutionary tableau.

The Corpse and the Cult

They tied his body to the landing skids of a helicopter and flew it to Vallegrande, where soldiers and CIA agents posed for photos with the corpse. The image — shirtless, eyes open, surrounded by gawkers — looked uncannily like a crucifixion. The world saw it and wept or cheered, depending on their politics. The CIA, masters of irony, had just turned him into a saint.

The Bolivians buried him in a secret grave, but the myth refused to stay underground. Che became an icon of defiance, a logo of cool rebellion for people who never read a word of his speeches. His face — that perfect storm of bone structure and righteousness — was plastered on T-shirts, vodka ads, and college walls. Somewhere in capitalist heaven, Marx was rolling in his grave while the marketers cashed in.

His writings were published, his legend inflated. He was no longer the man who executed dissidents and failed at logistics; he was the eternal revolutionary, the romantic corpse, the symbol of pure resistance. Jean-Paul Sartre called him “the most complete human being of our age,” which probably says more about Sartre’s standards than Che’s sainthood.

Meanwhile, Cuba embalmed his memory the way it embalmed everything else — in slogans and statues. “¡Hasta la victoria siempre!” became the revolutionary Amen. His bones were rediscovered in 1997 and flown back to Santa Clara, where they built him a mausoleum big enough to make Lenin blush.

Che had wanted to die in a blaze of revolutionary triumph; instead, he became the patron saint of disillusioned teenagers and Western consumer guilt. You can find him today staring out from fashion boutiques, coffee mugs, and iPhone cases — the capitalist afterlife of a man who tried to destroy capitalism.

The Man, the Myth, the Merchandise

Che’s life reads like a tragicomic morality play about idealism weaponized. He was brave, brilliant, and utterly insufferable — a man who believed violence could cure inequality the way chemotherapy cures cancer: by killing everything first. He preached self-sacrifice and lived it, even when it killed his followers. He loathed hypocrisy but drowned in it, a Marxist missionary with a Swiss watch.

To his admirers, he’s the Christ of the Left — slain for humanity’s sins, eternal in his purity. To his critics, he’s a murderous zealot whose incompetence got people killed. Both are right. That’s the trick of mythmaking: it sandpapers the contradictions until the icon fits the need.

The real Che was neither saint nor demon — just a man too convinced of his own righteousness to see the collateral damage. His courage was real; so was his cruelty. He fought for the poor but distrusted them. He despised capitalism but became its most bankable image.

In the end, the revolution devoured him — not in a blaze of glory but in a slow, miserable unraveling. His last breath was taken not in Havana’s triumph or Congo’s chaos but in a forgotten schoolroom, staring down a terrified conscript with an M2 carbine. The hero’s death he wanted became a photo op. The irony would’ve made him furious — or maybe proud.

Because if you squint hard enough, dying for a doomed idea still counts as victory. And Che, more than anyone, understood that immortality doesn’t require success — just a good pose, a few quotable lines, and a corpse that looks good on camera.

He dreamed of lighting the world on fire. Instead, he became the matchbook.

Warrior Rank #181

Sources:

Jon Lee Anderson, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (Grove Press, 1997).

Jorge Castañeda, Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara (Knopf, 1997).

CIA Declassified Files, “Death of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara” (1967).

Fidel Castro, History Will Absolve Me (1953).

The Motorcycle Diaries (2004 film, where Che learns that poverty sucks and so does riding in the rain).

“Che Guevara: The T-shirt Messiah,” The Economist (2007).

Revolutionary Chic: How Marx Lost to Marketing (imaginary but probably accurate).

Simon Sebag Montefiore, Titans of History (2012).

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125