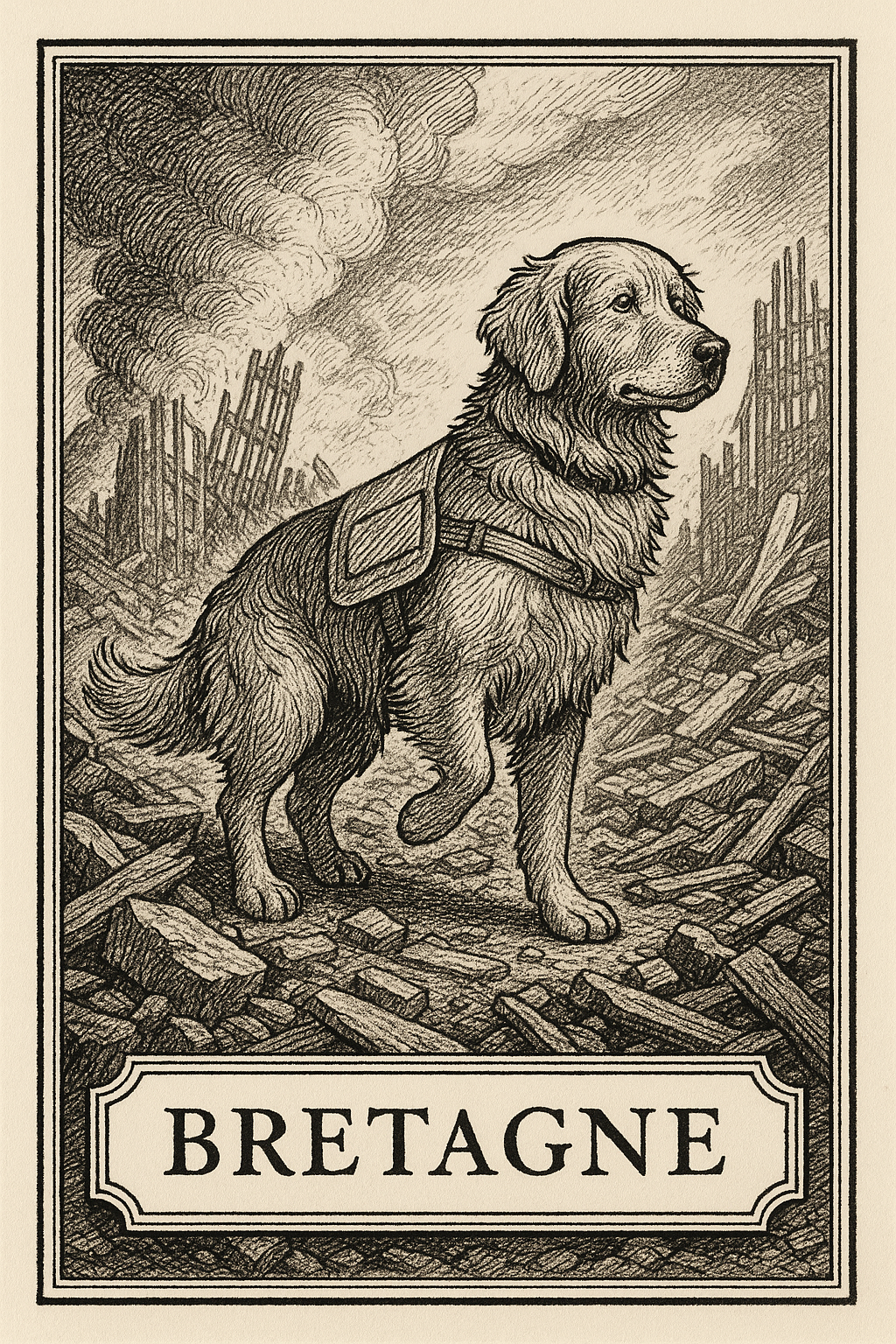

Bretagne

The golden retriever who outlived the smoke.

September 12, 2001 — Lower Manhattan. The air was a burning chemical fog, dense enough to taste. The towers were gone, replaced by a mountain of ash and glass. Firefighters and police moved through it like ghosts made of grit, calling names that would never answer. Somewhere in the gray, a golden retriever lifted her nose, caught a scent beneath the stench of jet fuel, and began to dig. Her handler, Denise Corliss of the Texas Task Force 1, followed silently. The dog’s name was Bretagne — pronounced “Brittany,” like the coastline that never sleeps — and she was three years old, eager, gentle, and newly trained for disaster. By the end of the week, she was covered in dust, her fur turned the color of ruin.

She’d come from suburban beginnings, a search-and-rescue program in Cypress, Texas. Her training was methodical: scent cones, rubble piles, commands in short bursts of optimism. She learned to find the living, to ignore the dead, and to bark only when she’d found hope. Nothing in the drills prepared her for New York. At Ground Zero she worked twelve-hour shifts beside firefighters and cadaver dogs, climbing steel skeletons slick with ash. She crawled through voids where stairwells used to be, slipped on melted glass, and kept moving. Her paws split open. Corliss wrapped them in duct tape and gauze, and Bretagne kept searching.

Rescuers began treating her like a colleague. They spoke to her softly, fed her bottled water, wiped her eyes with saline. When she found no one alive — which was most of the time — she sat beside the spot until someone came to mark it. Grief needed ritual, and she supplied it. One firefighter later said she “reminded us to breathe.” Another, interviewed years later, said she was “the only thing still unbroken.”

When the formal search ended, Bretagne left behind 1.8 million tons of wreckage and the names carved into granite that replaced it. She went home to Texas, resumed training, and deployed again: first to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, then to Hurricane Rita. By then her muzzle was whitening, her hips stiffening, but she kept showing up. She never found fame the way mascots or military animals did; her job was to be steady, to arrive where the world fell apart.

In retirement, she visited elementary schools and reading programs, lying patiently while children stumbled through sentences aloud. They’d rest their hands on her back without realizing they were touching history. Corliss called it “her soft deployment.” Parents cried in parking lots and didn’t explain why. Bretagne didn’t need to understand. She was there, which was most of the work.

By 2016, her body began to fail — kidneys first, then joints. When the time came, firefighters lined the walkway outside her veterinary clinic in Cypress, saluting as she walked in one last time. She wore her search-and-rescue vest, sun faded and frayed. Flags were lowered. The men and women who’d dug beside her fifteen years earlier stood silent, dustless this time, but no cleaner.

She was thirteen. They called her the last 9/11 dog, though that was only half true — there were others, scattered, unnamed, gone quietly before her. But she had outlasted the smoke, and that was something. Her ashes were placed in a flag-draped box, her vest folded over the top. Someone slipped in her favorite toy. Someone else whispered, “Good girl.”