Ham

The space chimp who took humanity’s first cruise in orbit.

January 31, 1961 — Cape Canaveral, Florida. Dawn through fog, the metallic scent of rocket fuel thick on the air. Inside the narrow capsule, a chimpanzee named Ham sat strapped in a molded couch, electrodes on his chest, sensors glued to his hands. He had been trained to pull levers when lights flashed — reward was a banana pellet, punishment a jolt of electricity. His heartbeat registered at 200 before launch.

Ham was three and a half years old, the first chimp chosen by NASA’s “Project Mercury.” The mission: test if a living body could think and move under rocket pressure. The engineers called him Number 65 to keep from forming attachments in case he died. Someone later broke the rule and gave him a name, borrowed from the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center: H.A.M.

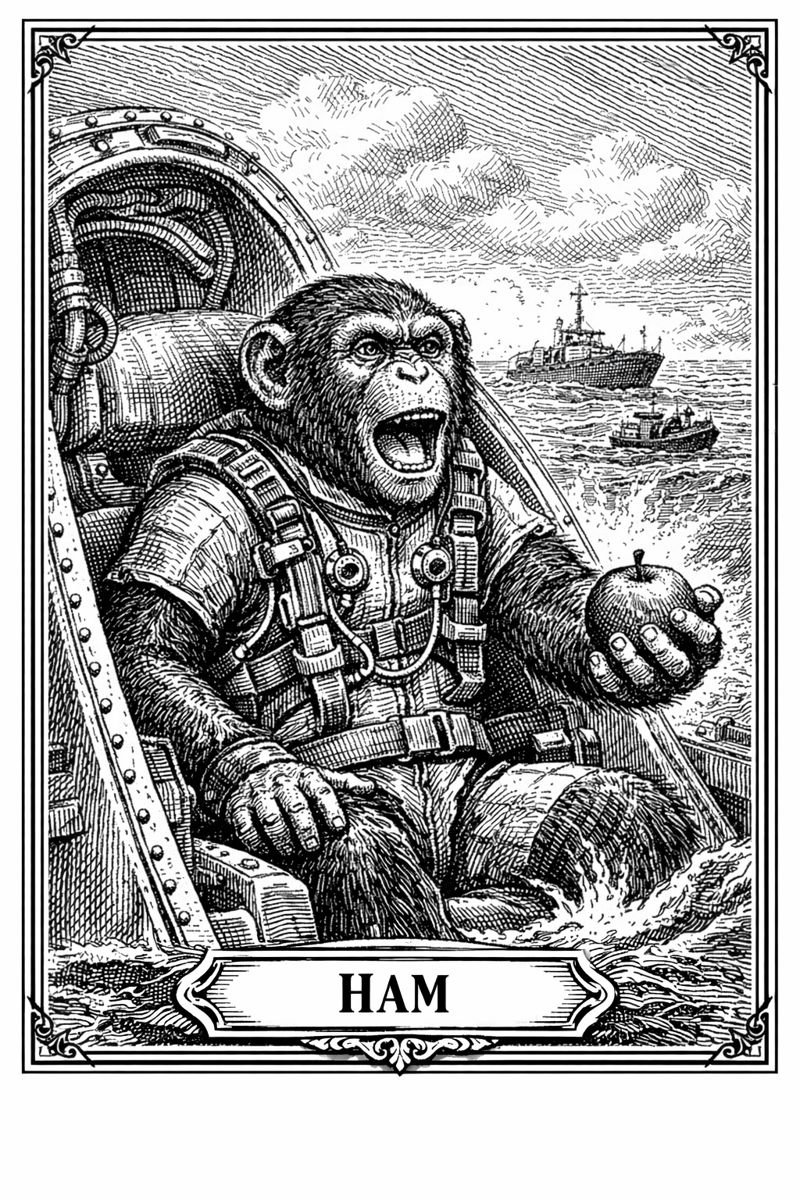

At 11:55 a.m. the Mercury-Redstone 2 rocket ignited. For 16 minutes he rode the edge of Earth’s atmosphere, weightless, instruments failing. Cabin pressure dropped; the capsule overheated. He still pulled every lever on cue. The craft splashed down 130 miles off course, slamming into the Atlantic. The recovery crew found him soaked, furious, but alive — teeth bared, lungs screaming at the sky.

When they opened the hatch, he reached out, shaking with adrenaline, and took an apple from the flight surgeon’s hand. The newspapers called him a hero; the lab called him data. The next mission, with a human pilot, used his telemetry to map the dangers he’d endured.

Ham spent the rest of his life in zoos, first in Washington D.C., later in North Carolina. Children pointed at him through glass, the “space chimp.” When he died in 1983, they buried him at the Space Hall of Fame in New Mexico. The stone over his grave carries the NASA emblem and a line as brief as his flight:

“Ham — The First Astronaut.”

He had gone farther than any of them knew how to thank him for.