Harambe

The silverback martyr of modern spectacle.

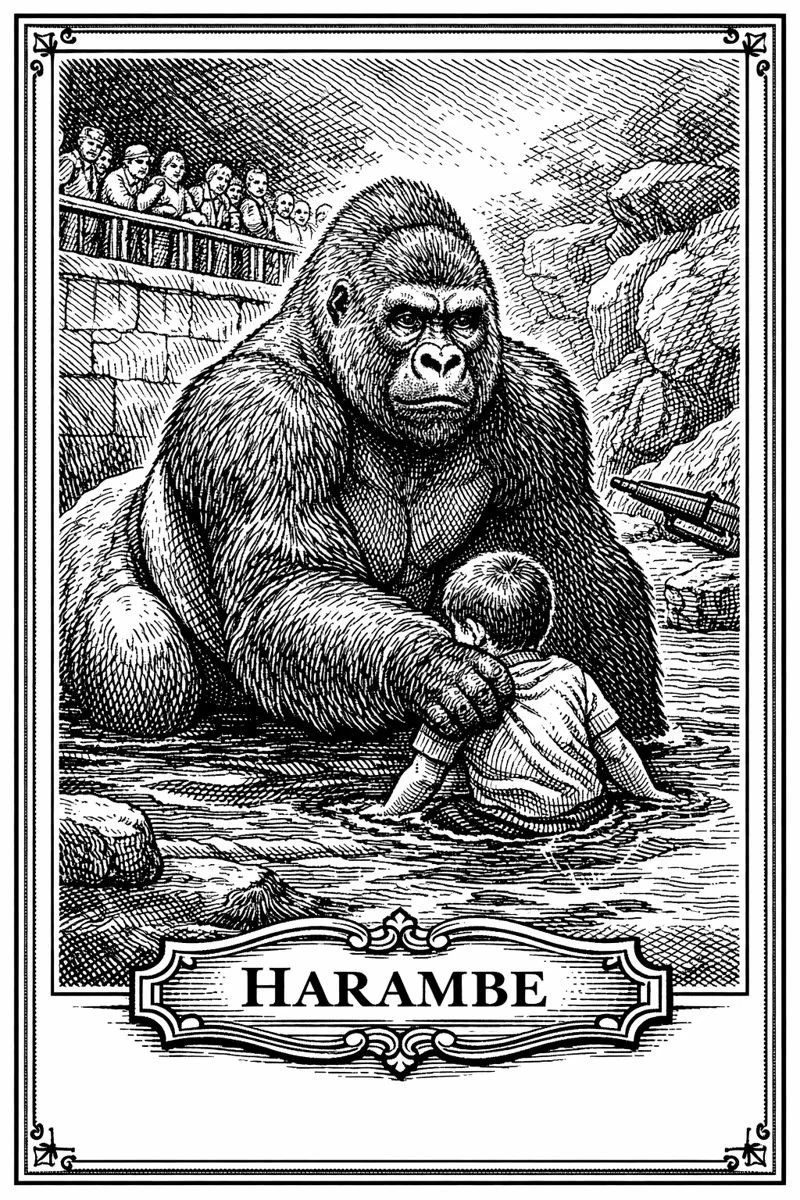

May 28, 2016 — Cincinnati Zoo. Afternoon heat pressed against the concrete moat of the Gorilla World enclosure. Families leaned over the railing, cameras raised. A three-year-old boy slipped through the barrier, tumbled fifteen feet down, and landed beside the 440-pound western lowland gorilla named Harambe.

The crowd screamed. Harambe approached — slow, curious, uncertain. He touched the boy’s back, then took him by the leg and dragged him through the water, half protective, half panicked. Zookeepers shouted. The tranquilizer would take too long. A single rifle shot echoed across the exhibit.

Harambe died in seven seconds. The boy lived.

The footage spread before the blood dried. Within hours, the world had opinions — outrage, grief, blame, memes, petitions, jokes. His name became a hashtag, a chant, a punchline. Millions mourned him, though few had ever known a gorilla’s face before that day.

He had been born in Texas, raised in social groups, transferred between zoos as part of a conservation program. His species was already endangered. His death became a digital resurrection: the internet’s first martyr of attention.

The zoo staff received death threats. The child’s mother vanished from public view. Statues, songs, graffiti — RIP Harambe — appeared across cities. For months, the world talked about him as if guilt could reverse a bullet.

His body was cremated, his remains kept private. The official statement read: “The choice was heartbreaking, but necessary.”

Harambe’s image endures — a reminder of what happens when a wild thing meets the lens, when compassion and spectacle collide, and neither species wins.