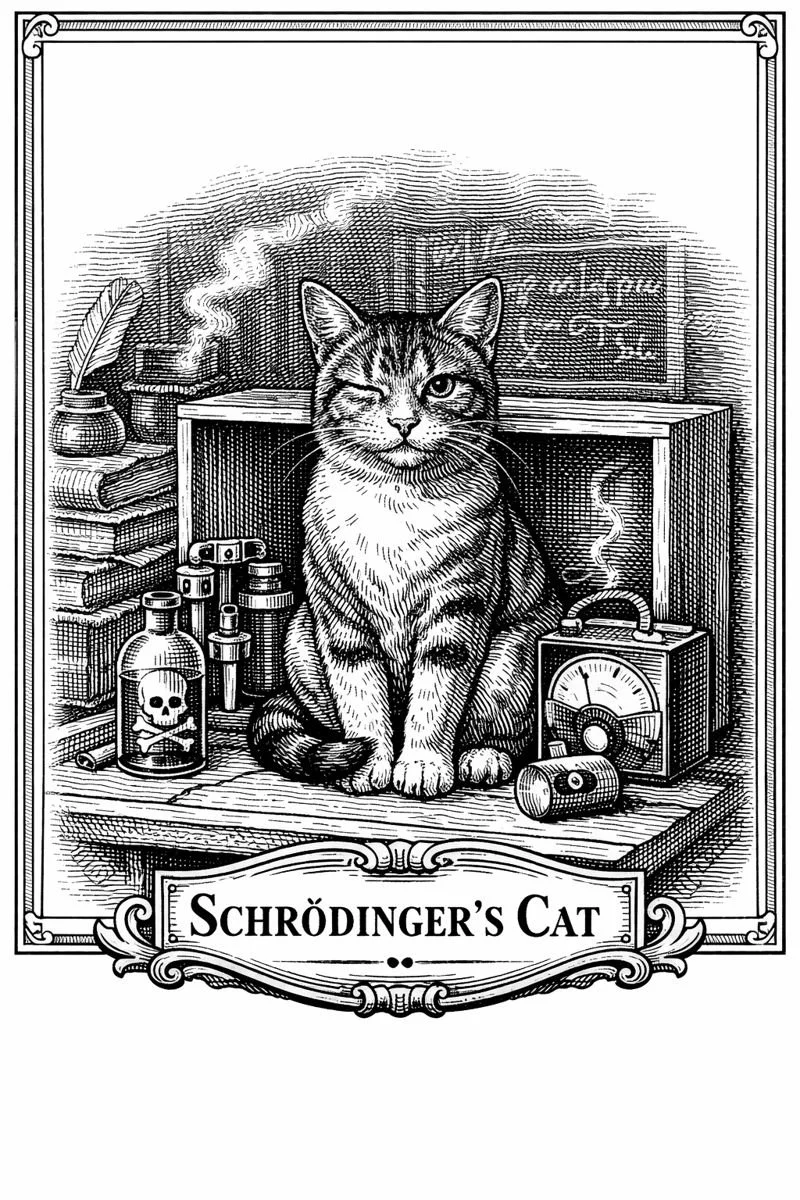

Schrödinger’s Cat

The paradox that proved imagination fatal.

Vienna, 1935. The study smelled of pipe smoke and chalk dust. On the desk, a physicist drew a box — ordinary, wooden, theoretical. Inside he placed a cat. Alongside it, a vial of poison, a lump of radioactive material, and a Geiger counter. The rules were simple: if the atom decayed, the mechanism would trigger, and the cat would die. If it did not, it would live. Until observed, he said, it would be both.

Erwin Schrödinger wasn’t trying to invent cruelty; he was trying to corner reason. Quantum mechanics had claimed that particles existed in all states at once until measured — probability as reality. He made the thought experiment monstrous on purpose, to show how absurd that sounded when translated into flesh.

There was never a real cat. But somewhere between metaphor and mathematics, the image took root. In lecture halls and cartoons, the box became eternal, the cat immortal — forever alive, forever dead, a prisoner of theory. Students laughed at the paradox. Philosophers argued its meaning. Physicists debated what “alive” even meant in a world governed by uncertainty.

Schrödinger himself grew tired of it. He later wrote that the cat had been “misunderstood and overworked.” But it was too late. The experiment had become folklore — an emblem of both genius and unease.

If the cat could speak, it might say the lesson was simpler: that human imagination, once set loose, can make anything suffer, even an idea. In every classroom where the box is drawn, it waits again, suspended between mercy and curiosity — proof that sometimes thinking about cruelty is enough to make it real.