Beheading

The Clean Cut of Sovereignty

Europe, Middle East, East Asia — Antiquity to the 21st Century

They called it mercy because it was quick. They called it honor because it was reserved. On the scaffold the air smells of wet wood, iron, and old prayers rubbed thin by repetition. A blade waits above a kneeling body like a punctuation mark deciding the sentence. The crowd leans in, not for blood but for closure. This is not a killing meant to linger. It is meant to end things. Cleanly. Decisively. With a sound that everyone pretends not to hear.

Justice, here, does not rage. It edits.

The Method — The Craft of the Cut

Beheading is among humanity’s oldest solutions to authority gone wrong. The method is brutally simple: separate the head from the body. The tools vary by culture and century. In early Europe, a sword or axe. In Scandinavia, the executioner’s axe with a broad blade and weighted head. In Japan, the katana, applied after ritual suicide to spare prolonged agony. In revolutionary France, the guillotine, a machine designed to remove the last excuses from human error.

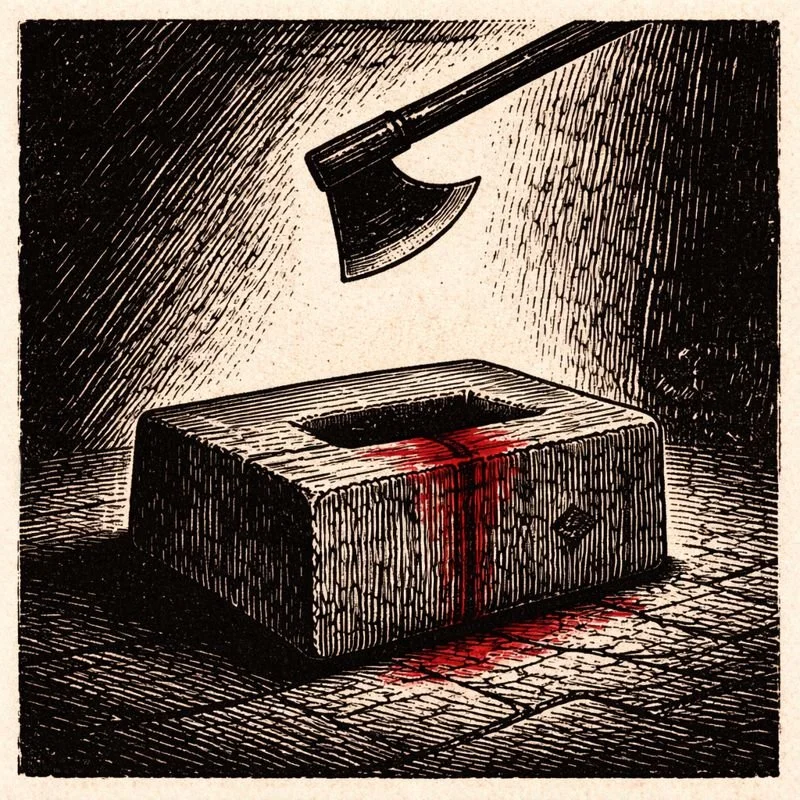

The body is positioned to invite gravity’s cooperation. Kneeling, bent forward, neck exposed. Sometimes a block. Sometimes a plank. The blade must fall or swing with enough force to sever vertebrae, muscle, and tendon in one decisive motion. A clean execution is a professional one. A botched cut is remembered for centuries.

Beheading flourished where hierarchy mattered. Nobles were beheaded. Commoners were hanged, burned, broken. The head was considered the seat of reason, identity, and divine breath. To remove it was to erase the person in a way fire could not. It was both an end and a display.

Across continents, the logic held. In China, decapitation was among the “five punishments,” reserved for the gravest crimes. In the Islamic world, the sword carried both judicial and symbolic weight, echoing battlefield justice. Empires favored methods that spoke clearly. A severed head speaks.

The Human View — Neck-Level History

For the condemned, time distorts. Knees ache. The wood is colder than expected. There is often a hood, sometimes not. Final words are requested, not always heard. The body prepares for pain it may never fully register. Neurologists still argue about seconds of consciousness. The crowd already knows the answer it prefers.

For the executioner, the act is labor. Reputation matters. Payment depends on competence. A single stroke is pride. Multiple strokes are shame. In some cities, the executioner lives on the edge of society, both necessary and untouchable. He sharpens the blade like a craftsman because that is what he is. The work does not allow philosophy.

For witnesses, beheading is theater without illusion. No flames to mesmerize. No prolonged suffering to savor. Just anticipation and aftermath. The head is often displayed, held up by hair or shown to the crowd. Proof is part of the ritual. The body collapses like a marionette cut free. The crowd exhales.

The Society Behind It — Order in One Motion

Beheading teaches a specific lesson: power is centralized, swift, and irreversible. It is punishment without chaos. States that favor beheading favor clarity. The condemned is not tortured into repentance. They are removed from the equation.

Religion often sanctified the act. A clean death suggested divine efficiency. Law wrapped itself in ritual to avoid the appearance of cruelty. The blade fell not in anger but in accordance with statute. This distinction mattered deeply to societies that believed order was fragile.

Public beheadings reinforced hierarchy. Only certain people qualified. To be beheaded was, perversely, a privilege. It acknowledged status even in death. The crowd learned who mattered by how they died.

And always there was the head itself. Displayed on spikes. Preserved in salt. Sent to distant cities as political correspondence. The message traveled faster than armies.

Historical Record — Heads That Changed History

In 1536, Anne Boleyn knelt on the green at the Tower of London. Henry VIII imported a French swordsman for the job, a gesture of both efficiency and irony. One stroke. A queen reduced to evidence. England learned that marriage was provisional.

In 1649, Charles I was executed outside Banqueting House. The scaffold was built low, the crowd dense. When the blade fell, monarchy itself seemed to flinch. Europe watched in disbelief as a king became a corpse. (See also: Charles I — from The Warrior Index.)

In 1793, Louis XVI died beneath the guillotine, the Revolution’s favorite verb. The machine was meant to democratize death. It succeeded. Nobles and peasants alike fed the blade. The head was shown to the crowd. The crowd cheered, then learned how easy cheering becomes.

Beyond Europe, the record widens. Samurai carried out kaishakunin, decapitating comrades after seppuku to preserve honor. In the Ottoman Empire, heads were stacked to count victories. In ancient Rome, decapitated heads of enemies adorned the Forum during civil wars. The method traveled because it worked.

Myth & Memory — The Head That Would Not Be Silent

Beheading attracts myths like iron filings. Tales of blinking eyes, moving lips, whispered curses. The guillotine inspired rumors of heads that lived long enough to think. Science remains cautious. The stories persist.

Art embraced the image. Caravaggio’s severed heads. Medieval illuminations with tidy red lines. Modern cinema slows the moment, stretching the cut into spectacle. The head remains compelling because it is us, separated from everything else.

In modern times, beheading is officially abolished in most legal systems, yet it survives in atrocity videos and propaganda, stripped of ritual and drenched in spectacle. The old logic returns without the old restraints. The blade still speaks. It just speaks to cameras now.

Memory reframes the act. We call past beheadings barbaric, forgetting how carefully they were designed to be humane. We replace blades with paperwork, scaffolds with policies. The desire for decisive endings never leaves. It just changes costume.