Cúchulainn

(319 BCE – 292 BCE)

He died on his feet so Ireland wouldn’t have to—but she did anyway, again and again, just to keep him company.

"When your nickname comes from killing your best friend’s dog, you either become a legend or a war crime." — Old Ulster saying, probably

The boy was twelve when he first painted the battlefield red. Twelve. The rest of us were still worrying about freckles and puberty. Cúchulainn—born Sétanta mac Sualtaim—was worrying about how many skulls he could fit into one afternoon.

Picture it: Ulster, somewhere between myth and hangover, the air heavy with mead, machismo, and the metallic tang of destiny. Ireland was still a playground for gods, druids, and people who thought turning into swans was a reasonable solution to most problems. And into this merry pagan brawl strolls a kid with a stick, a sling, and the kind of overconfidence usually found only in demigods and first-year philosophy students.

He wasn’t supposed to be special. His mother, Deichtine, was Conchobar’s sister (that’s King Conchobar mac Nessa of Ulster, patron saint of terrible decisions), and his father was—depending on which bard you ask—either a mortal named Sualtam or the literal god Lugh. Either way, little Sétanta came out swinging. The boy could hit a flying apple off a horse’s ass from fifty yards. He could also, inconveniently, fly into a berserker rage that made rabid badgers look polite.

“I Only Killed the Dog Because It Barked at Me”

The legend starts with a party—because of course it does. Conchobar was invited to the smith Culann’s feast, and young Sétanta tagged along late, having been off demolishing some hapless hurling team. When the smith’s massive guard dog (think Irish Wolfhound crossed with a mythological landmine) charged the boy, Sétanta did the only rational thing: he killed it. With a sliotar.

Embarrassed but unrepentant, he promised to take the dog’s place until a new one could be raised. Thus: Cú Chulainn, “the Hound of Culann.” The world’s first volunteer canine replacement.

It’s an oddly fitting metaphor—he would spend his short, furious life chained to duty, loyalty, and the throat of anyone dumb enough to attack Ulster.

Boy Wonder Goes Berserk

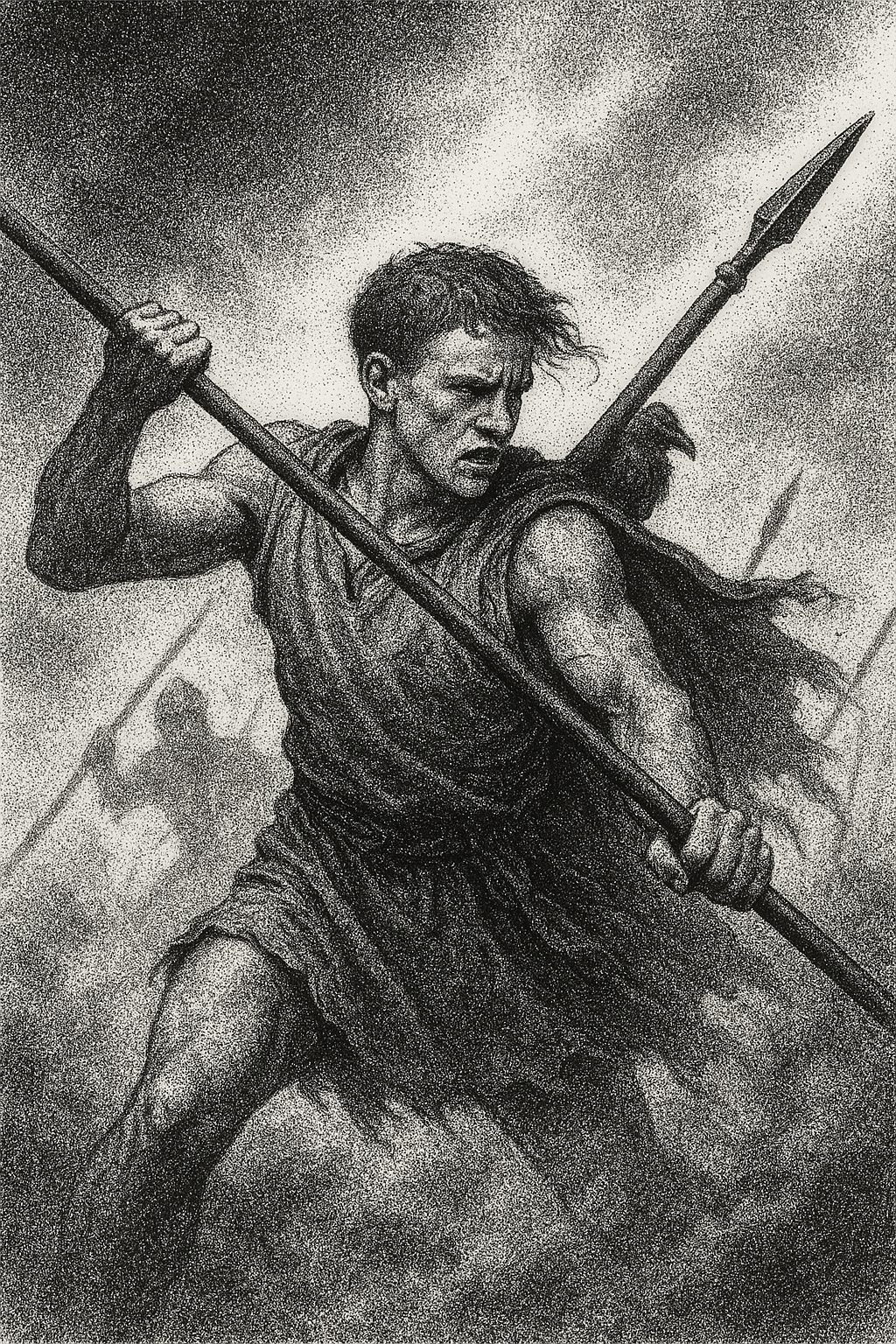

By seventeen, Cúchulainn was Ulster’s human hurricane. His ríastrad—the warp-spasm—was the Irish version of going Super Saiyan, except uglier. His body twisted, bones popped, muscles ballooned, one eye shrank into his skull while the other bulged out like a crab apple, and blood hissed into vapor around him. He basically turned into a demonic pretzel powered by fury and bad decisions.

He didn’t just kill people. He disassembled them. He could turn a battlefield into a Jackson Pollock painting made entirely of viscera and hubris.

When the Connacht queen Medb (pronounced “Maeve,” spelled like a typo) decided she wanted Ulster’s prize bull—the Donn Cuailnge—she launched an invasion known as the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley). Unfortunately for her, the Ulster warriors were all incapacitated by a curse that hit them with something between food poisoning and divine syphilis. So, naturally, teenage Cúchulainn defended the entire province alone.

One-Man Apocalypse

What followed reads like the fever dream of a drunk Homer. Every day, another champion of Connacht would show up at the border, and every day, Cúchulainn would kill them, usually in some spectacularly inefficient way. He decapitated friends, gutted cousins, and once killed a guy with his own chariot wheel. He was the original “You shall not pass,” except instead of a wizard’s staff, he had a spear that screamed when thrown.

When the enemy tried to sneak by, he built a wall of corpses. When they tried to bribe him, he laughed. When his foster brother Ferdiad—his closest friend and sparring partner—was sent against him, he begged him not to fight. Then he killed him anyway.

They say when Ferdiad fell, Cúchulainn cradled him and wept until his tears turned to blood. It’s one of those tragic moments bards love and therapists could retire on.

Death by Prophecy (and Spite)

You can’t be that good for that long without fate noticing. Cúchulainn’s death was prophesied early—he’d live a short life, glorious and gory. He said fine. He’d rather burn bright than fade out.

Eventually, the odds caught up. A spear cursed to kill the one it struck—and the hand that threw it—found him. It tore through him like divine karma. His guts spilled out, but he refused to fall.

He staggered to a standing stone, tied himself upright, and died on his feet. Enemies crept near but didn’t dare touch him until a raven landed on his shoulder. Only then did they believe he was finally dead.

A raven—the symbol of the Morrígan, goddess of war and fate—his old lover, his sometime nemesis. Even in death, he couldn’t escape women or symbolism.

Resurrection by Myth

Cúchulainn didn’t stay dead. He never does. Bards kept resurrecting him in verse, monks cleaned him up for polite Christian company, and nationalists later turned him into a Celtic Captain America.

The rebels of 1916 Dublin invoked him as Ireland’s eternal defender. WB Yeats wrote poetry about him. There’s a bronze statue of him dying, upright, intestines elegantly draped—on display in the General Post Office in Dublin, the rebel headquarters during the Easter Rising.

He’s become an immortal metaphor for doomed resistance—a patron saint for anyone who dies too young, too proud, or too stupid to quit.

Madness and Myth Collide

Underneath all the heroic varnish, though, he’s a portrait of pure burnout. The warp-spasm wasn’t just magic—it was trauma in mythological form. The boy who killed a dog for barking became the man who slaughtered an army for trespassing. Every kill twisted him further until he couldn’t tell victory from damnation.

Cúchulainn is what happens when duty devours the human beneath it. When the war hero realizes he’s just another dog—leashed to a cause, gnawing bones tossed by kings and queens who’ll forget his name once the blood dries.

And yet, the Irish keep him. Not as a saint or a monster, but as something beautifully cursed—a reminder that courage and madness are separated only by poetry and hindsight.

He fought gods, ghosts, and cows, and the cows might have been the hardest. He killed his best friend, was betrayed by prophecy, and tied himself upright so the world couldn’t watch him fall. The Hound of Ulster lived like a meteor and died like a monument.

They say his eyes still burn in the hills when storms come in off the sea, watching for the next fool who mistakes rage for honor.

Because every age needs its own Cúchulainn—right up until he turns on you.

Warrior Rank #190

Sources (Mostly Real, Some Questionable):

Kinsella, Thomas, trans. The Táin. Oxford University Press, 1969.

Rees, Alwyn and Brinley Rees. Celtic Heritage: Ancient Tradition in Ireland and Wales. Thames and Hudson, 1961.

Yeats, W. B. Cuchulain of Muirthemne. 1902.

Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Myth, Legend & Romance: An Encyclopedia of the Irish Folk Tradition. Prentice Hall Press, 1991.

The anonymous drunk who insists Cúchulainn was “basically Irish Batman.”

That one guy at the pub who swears his cousin’s cousin is descended from him.

A raven, whispering spoilers since 1st century BCE.

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125