Otto Skorzeny

(1908–1975)

The Scarred Daredevil of the Third Reich

“I never lost a war—just my country, my uniform, and my goddamn moral compass.”

—attributed to Otto Skorzeny, possibly while drunk and tanning on a Spanish beach.

The Wolf with a Scar

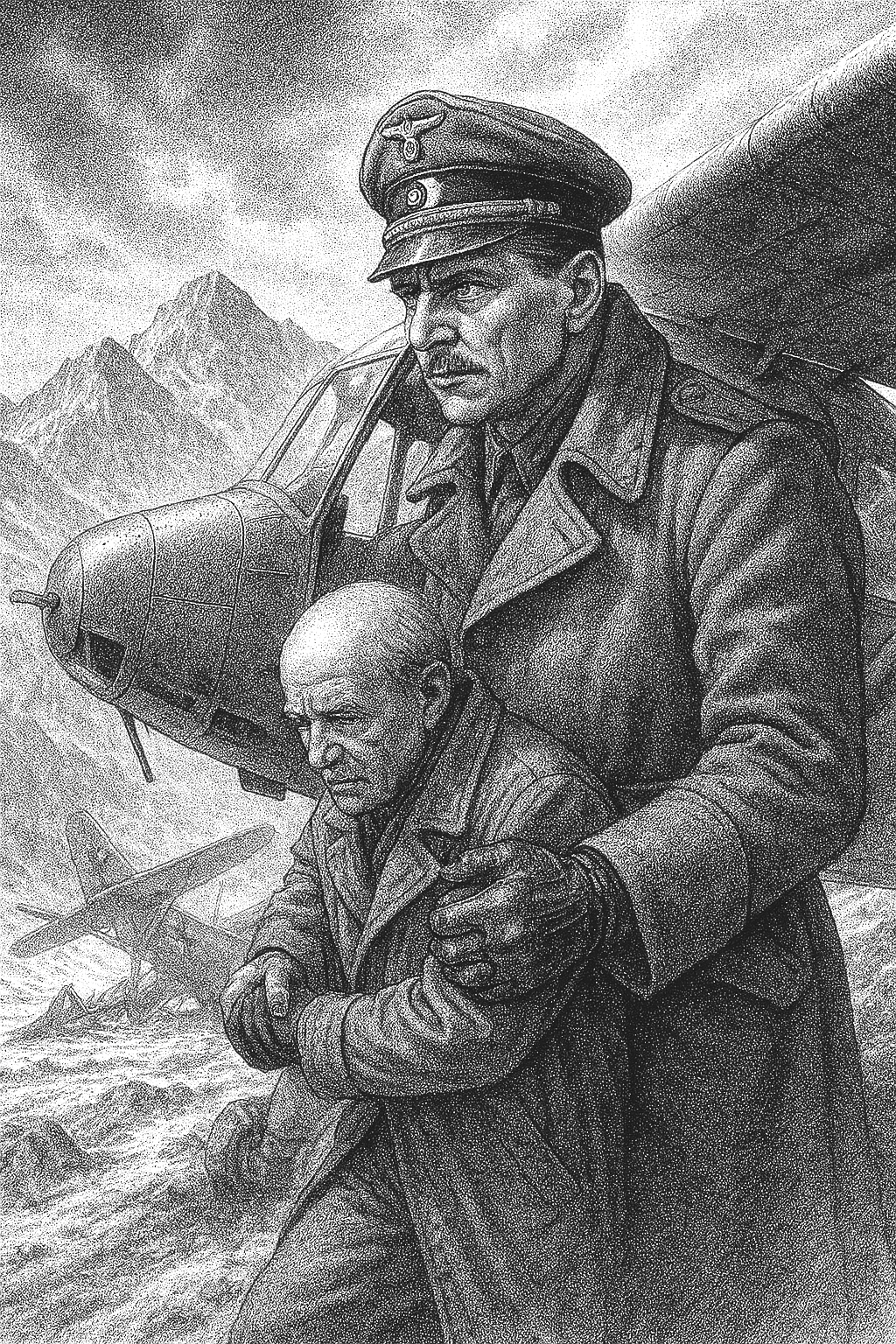

It’s September 1943, and the sky over central Italy is full of noise that doesn’t belong there. German gliders are screaming through the thin Apennine air, cutting toward a mountaintop hotel where one of history’s great narcissists sits sulking. Inside one of those gliders is Otto Skorzeny—a man who looked like a villain designed by pulp fiction: tall, scarred, and possessed of a confidence that bordered on religion. The scar, a fencing wound from his university days, wasn’t a mark of battle, but it did wonders for his legend. To Nazi propagandists, it said: here is a man who has fought, bled, and smiled about it.

Down below, the Hotel Campo Imperatore looks less like a prison and more like an accidental shrine to fascist incompetence. Benito Mussolini, freshly overthrown by his own people, has been locked away by his former allies, guarded by men who aren’t sure which way the war is going. Then Skorzeny drops in—literally. Operation Eiche, the grandly named “Oak Tree” rescue, is one of those insane plans only the Third Reich could approve: land gliders on a mountaintop, snatch Mussolini from captivity, and fly him out before anyone realizes the war is lost.

It works. Against all odds, Skorzeny and his men burst into the hotel, guns out, boots heavy, fascist flair in full bloom. Not a single shot is fired. The Italian guards surrender instantly—perhaps out of fear, perhaps from sheer confusion. Ten minutes later, Mussolini is shaking Skorzeny’s hand and declaring him a hero. In Berlin, Goebbels calls him “the most dangerous man in Europe.” Hitler beams like a proud father. And Otto Skorzeny, who just became a myth, doesn’t bother pretending to be humble about it.

Building a Monster

Before he was the Reich’s favorite swashbuckler, Otto was just another ambitious Austrian. Born in Vienna in 1908, he studied engineering and joined the Nazi Party before it was cool—1931, back when it still smelled more like street fights and beer halls than world domination. He fenced, drank, and memorized Wagner. He also absorbed the ideology like a dry sponge: nationalism, obedience, and a taste for spectacle.

When war broke out, he joined the Waffen-SS and worked his way up the ranks not by being subtle but by being useful. He wasn’t a front-line grunt; he was a thinker who preferred chaos with blueprints. Skorzeny specialized in unconventional warfare—behind-the-lines sabotage, commando raids, psychological trickery. In another life, he’d have been a stunt coordinator. In this one, he was a Nazi with a flair for the theatrical.

The Mussolini rescue catapulted him from officer to celebrity. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross, photographed endlessly, and paraded as a symbol of German daring. In a regime full of hollow-eyed bureaucrats and true believers, Skorzeny stood out because he seemed to actually enjoy it. He wasn’t serving ideology—he was serving the thrill.

The Man Who Stole the Ardennes

By 1944, the war was collapsing like a wet cardboard fort. Hitler’s solution was to gamble everything on one last offensive: the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge. It was supposed to split the Allies, take Antwerp, and force peace. It did none of those things, but it gave Skorzeny another chance to play war like a mad scientist.

His new task: Operation Greif. The mission was pure mischief—disguise German soldiers as American MPs, infiltrate enemy lines, sow confusion, and cause chaos. Skorzeny’s men, dressed in stolen U.S. uniforms and jeeps, went behind enemy lines to switch road signs, misdirect convoys, and spread rumors that Eisenhower was about to be assassinated. It was psychological warfare at its pettiest—and it worked better than it had any right to. American forces descended into paranoia. MPs detained each other at gunpoint. Checkpoints started demanding trivia questions: “Who won the World Series?” “What’s the capital of Illinois?” Some soldiers who didn’t answer fast enough got shot.

Skorzeny became the bogeyman of the Bulge—a shapeshifter, the Nazi who might be wearing your uniform. Even after his men were captured, the myth snowballed. Eisenhower himself was briefly confined for his own safety. For a few delirious weeks, one scarred Austrian had half the U.S. Army looking over its shoulder.

After the Fall

When Berlin finally fell apart in 1945, Skorzeny didn’t go down with it. He surrendered to the Americans, figuring they’d rather talk to him than shoot him. He wasn’t wrong. The Allies were fascinated by him. A man who could pull off miracles for Hitler might be useful for them too, in this new Cold War that everyone could feel forming like a hangover.

At Nuremberg, he was tried for war crimes—not for the massacres or genocide, but for improperly wearing uniforms. That’s right: in a war that redefined evil, Otto Skorzeny was in court for violating the dress code. He defended himself by arguing that Allied commandos had done the same thing. Several British officers testified on his behalf. The tribunal shrugged and acquitted him. It was a stunningly absurd outcome, but that was the late 1940s: Nazis walked if they had good stories and better intelligence contacts.

For a while, he sat in an internment camp, then escaped—because of course he did—using a faked Red Cross pass and some forged papers. He fled to Spain, which under Franco was basically Club Med for unrepentant fascists. There he reinvented himself as a businessman, consultant, and occasional mercenary middleman.

The Mercenary Years

Spain in the 1950s was full of ghosts in good suits. Skorzeny fit right in. He ran engineering firms, dabbled in arms deals, and offered his expertise to anyone who could pay. For a man once hailed as Hitler’s “favorite commando,” he was remarkably adaptable. He advised Nasser in Egypt, trained pro-Arab guerrillas, and allegedly worked with Mossad on at least one mission to take out former Nazis who were inconveniently public. When asked about it later, Israeli agents confirmed, with exquisite irony, that they had used Otto Skorzeny—a former SS colonel—to kill other Nazis.

He also moonlighted as an advisor to Perón’s Argentina, a consultant for Irish nationalists, and a general nuisance wherever chaos paid cash. If the mid-century world had a problem that could be solved with sabotage, Skorzeny was the number they called before realizing what a moral disaster it was. He didn’t care. The ideology had died with the Reich. What remained was his addiction to action.

The Myth and the Man

Propaganda had birthed him, and myth refused to let him die. In the postwar years, Otto Skorzeny became pulp gold: the scarred commando, the daring rogue, the man who could turn defeat into a photo op. His image appeared in spy novels, Cold War thrillers, and half-accurate biographies that turned him into a cross between Errol Flynn and Satan. Some veterans respected him; most loathed him. The world, as usual, loved the story more than the truth.

And the truth was ugly: Skorzeny was clever, charismatic, and amoral. He wasn’t a genius tactician or a loyal soldier. He was an adrenaline addict who treated war like theater and people like props. He excelled at missions that looked good on film but changed nothing about the war’s outcome. He didn’t save the Reich—he just made its collapse look cinematic.

The Long Sunset

By the time he died in 1975—lung cancer, not bullets—Skorzeny was a tanned relic of a bad century, living in Madrid among fascists who still toasted “the good old days.” He gave interviews, smiled for cameras, and never once expressed regret. He said the SS had been “honorable men,” which was like calling the Titanic “a decent ship, overall.”

His funeral was attended by old Nazis, mercenaries, and right-wing romantics who saluted as if 1945 had been a bad dream. Someone played military music. Someone else cried. And somewhere, in the great bureaucratic afterlife, Otto Skorzeny probably checked in under a false name, grinning like a man who knew he’d cheated history one last time.

He spent a lifetime surviving his own legend. Few men could have done it so brazenly.

He died as he lived—half hero, half con man, and entirely full of shit.

Warrior Rank #179

Sources

Glenn B. Infield, Skorzeny: Hitler’s Commando (Macmillan, 1981).

Charles Whiting, Skorzeny: The Most Dangerous Man in Europe (Leo Cooper, 1998).

H. Trevor-Roper, The Last Days of Hitler (Pan, 1964).

Antony Beevor, The Fall of Berlin 1945 (Viking, 2002).

“Mossad’s Nazi Assassin,” Haaretz, April 2018.

Modern Warfare Monthly, “Operation Greif and the Great American Identity Crisis” (satirical reprint, 1979).

Beer Hall Quarterly, “Ten Fascists Who Should’ve Stayed Engineers.”

Charles XII of Sweden was a warrior-king who personally led his armies through the Great Northern War, turning early victories into legend through ferocious discipline and reckless courage. His refusal to compromise or retreat ultimately shattered Sweden’s empire, leaving behind a mythic figure admired for bravery and criticized for destroying everything he fought to protect.

Rank - 125